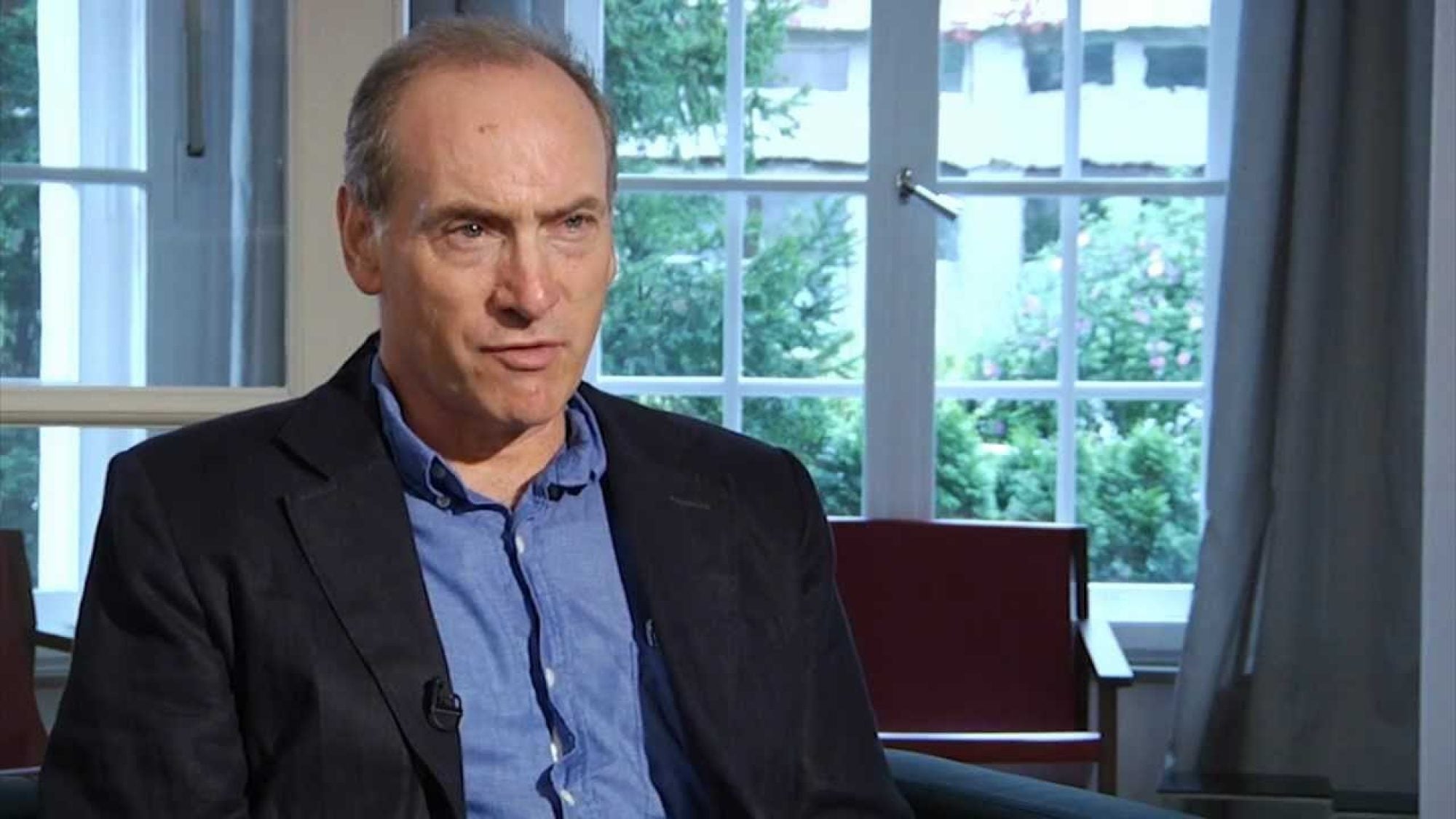

Title: Parallels and Precedents: Five Minutes with Historian John McNeill

On January 26th, 2012 historian John McNeill sat down with the Georgetown Journal to discuss America’s declining power, US-China relations and the potential formation of a global state.

[GJIA] Those who hypothesize about America’s declining power often point to historical examples to prove their point. Looking at American power today, would you say those forecasting America’s decline are misreading the past?

[McNeill] The odds are that the US position of the past sixty years will steadily erode, but that is not a conclusion based on historical precedent. It is a conclusion reached by considering the anomalies of US history since 1870. First, the US economy outperformed the rest of the world between 1870 and 1970. Since that time, its economic performance has been relatively ordinary, even weak, relative to growing competitors like China. Second, the US international position is partly due to the prostration of other powers in 1945, the economic advantages of an early conversion to oil and automated assembly lines (made from 1900 to 1930 in the US), and a post-Cold War hegemonic position owing largely to the self-inflicted wounds of the USSR/Russia. These conditions no longer apply.

Politicians of all stripes are obliged to be cheerleaders, parading their faith in the brilliance and energy of their constituents. In the US, elected officials must reassure voters that Americans are special and better and different. Many of them sincerely believe this, and imagine that American pre-eminence in the international system can be a permanent condition because the US is an exceptional case. I do not, and historical perspective is the main reason I do not.

[GJIA] What similarities or differences do you see with the situation developing between the US and China now and that which developed between the US and the Soviet Union after World War II?

[McNeill] I don’t see a strong historical parallel. In the late 1940s the US had all of the economic advantages and most of the geopolitical ones. For a period the US possessed half of the world’s industrial capacity and had politically-assured access to most of earth’s oil and coal resources. In post-1945 USSR, meanwhile, people were literally starving in provincial cities. Its political system had some appeal around the world, and it acquired an important ally (for ten years) with the 1949 Chinese Revolution. But its political position was effectively circumscribed by US containment efforts. Today, the authoritarian and nominally communist PRC has a much stronger economic and political position than that of the USSR from 1945 to 1991, while the US economic position is weaker relative to that of the late 1940s.

Importantly, China and the US are economically interdependent in a way that the US and USSR never were. China holds trillions of dollars of US debt and could destroy public finance in the US in a week if it so wished. But China also needs the US to keep buying its products. Even after the US started selling grain to the USSR in the 1970s those two economies were never greatly intertwined. In both cases the pairs of countries were by some measures the two strongest in the international system, but beyond this, I see only a weak parallel.

[GJIA] Would you agree that over the course of human history our species has demonstrated a tendency to collect into progressively larger organizational groups, and adapt political, economic and social institutions accordingly? Observing this trend, do you think a central global government is theoretically possible?

[McNeill] I not only believe that over time our species has a tendency to collect into progressively larger organizational groups, I know it! Fifty thousands years ago our characteristic social and political organization was the migratory band of 20-50 people, mostly kin. In places where a seasonally abundant supply of food might be had, a few hundred kinfolk might gather to exchange information, gifts, and young people in marriage. Larger political units had to wait for the foundation of states, which, as far as we know, took place first in Sumeria a little over 5,000 years ago. These brought a few thousand people together into a single polity, kin and non-kin alike.

The first imperial state was Sargon’s Akkad, roughly 4,400 years ago, the population of which was probably a few hundred thousand. It was a short-lived empire. Not until the Achaemenid Persian empire (6th-4th centuries B.C.E.) was there a state that ruled tens of millions of people and covered vast territory stretching from the shores of the Aegean to Afghanistan.

Does this help to make global government theoretically possible? Yes, but not likely any time soon. The sacrifices of sovereignty necessary to bring a consensus-based world state are too large to seriously consider at present. The EU’s travails show the difficulty of expanding a consensus. The expansions of scale represented in the history of Sumer, Akkad and Persia were achieved by military force, which seems a very unlikely route to a world state today. As long as there is cultural, linguistic and religious diversity, the achievement of a consensus state looks unreachable. So a central global government is theoretically possible, yes. A plausible scenario within this century, no.

. . .

This interview was conducted by Kenneth Anderson, a 2nd year student in the Masters of Science in Foreign Service program at Georgetown University and a managing editor of the Georgetown Journal.

John McNeill was born and raised in Chicago, and holds a B.A. from Swarthmore College and a Ph.D. from Duke University. Since 1985 he has served as a faculty member of the School of Foreign Service and History Department at Georgetown University. From 2003 until 2006 he held the Cinco Hermanos Chair in Environmental and International Affairs. He teaches, researches and directs Ph.D. students in the study of history, environmental history and international history. He lives an agreeably harried existence with his triathlete wife and their four exuberant children.

Image credit: Rachel Carson Center, Dr John. McNeil on “An Environmental History of the Industrial Revolution”.

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

Recommended Articles

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…