Title: Unraveling Bangladesh’s ICT and the Shahbag Protests: Injustice in the Making

On 28 February 2013, thousands of people in Shahbag square erupted in jubilation. Delwar Hossain Sayedee, a prominent member of the Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s largest Islamic political party, was sentenced to death by the International Criminal Tribunal (ICT). Since then, counter-protests in support of Sayedee have led to violent skirmishes with police. To date, over 60 deaths have been reported in the clashes.

If the actions of the ICT and the Shahbag protests continue in their present form, then justice risks being fully usurped by vengeance and dirty politics. The Shahbag protests have revealed that mob rules, if shouted loud enough, can overshadow justice.

The ICT, a domestic Bangladeshi tribunal, was set up in 2010 to try Razakars (collaborators with Pakistani forces) for atrocities committed during the nation’s struggle for independence from Pakistan in 1971. In its totality, the ICT is a glaring failure in terms of the rights afforded to accused individuals. Organizations including Human Rights Watch, the International Bar Association, Amnesty International, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, and the International Commission of Jurists have all voiced their reservations about the ICT.

The principle concern is that, due to constitutional amendments passed in 1973, the ICT is exempted certain safeguards in Bangladesh’s constitution. For example, the accused cannot ask for an independent court to review the laws, procedures, and interlocutory decisions of the ICT. When Sayedee sought a review of the ICT’s refusal to provide a clear definition of crimes against humanity, the ICT refused to review its earlier decision. Effectively, Sayedee was left without full knowledge of the accusations against him.

Further, the ICT’s Rules of Procedure fall significantly short of providing an accused with adequate procedural safeguards. Individuals under suspicion by the ICT can be arrested and questioned without any charges being laid. Sayedee was arrested on 2 November 2010 and was charged until 11 months later.

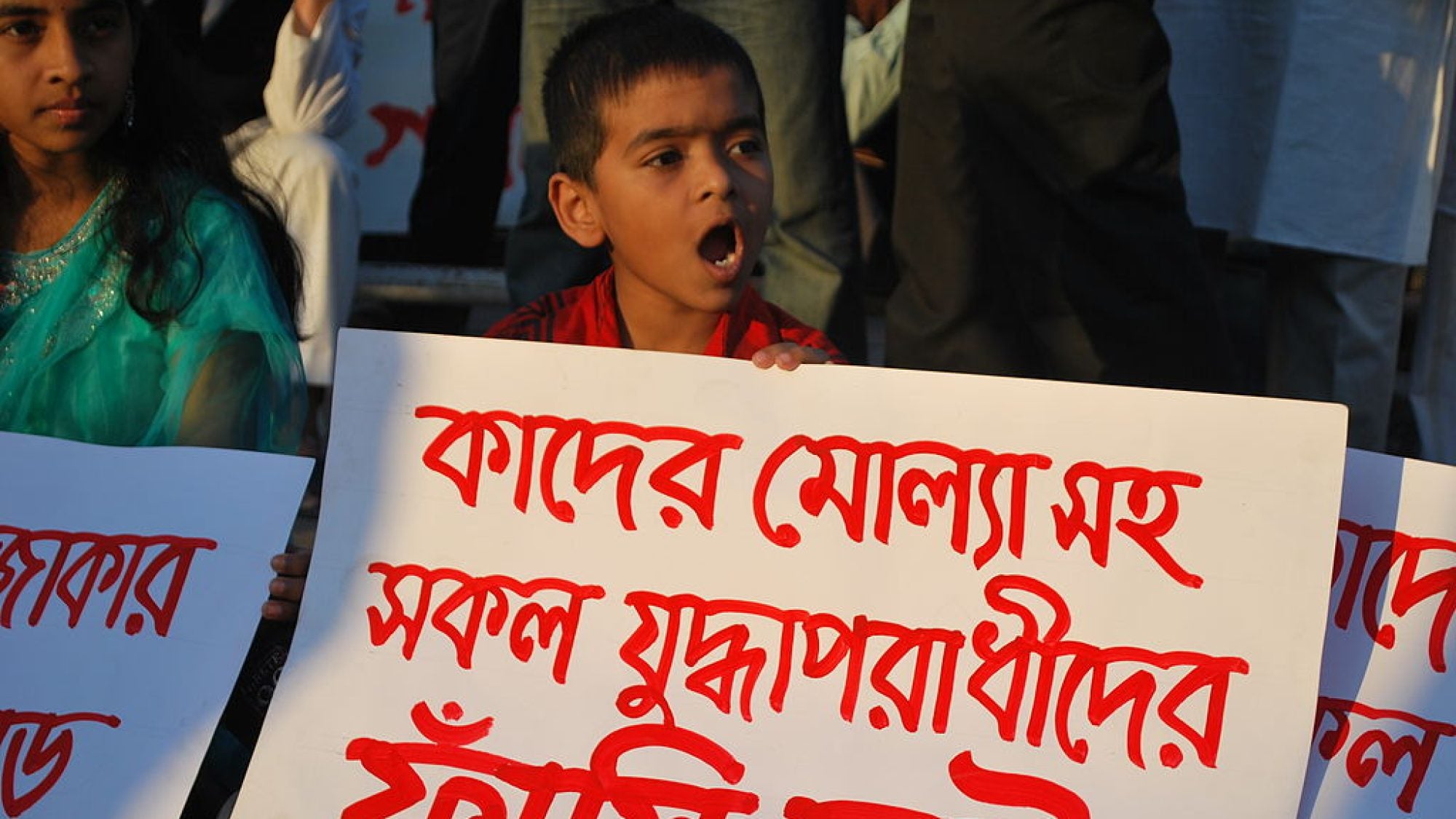

Questions have also been raised about the Awami League government’s interference in the present process. Upon the sentencing of Abdul Quader Mollah, a senior member of Jamaat like Sayedee, to life imprisonment, tens of thousands of protestors took to the streets, demanding that Mollah be sentenced to death. Taking advantage of the public opinion, the Awami League brought an amendment to s. 21(1) of the International Criminal Tribunal Act (compare the original and the amendment). The amendment provides the government with the right to appeal a final decision made by the Tribunal (such as Mollah’s sentence) to Bangladesh’s Supreme Court.

A basic maxim of law is nullum crimen, nulla poena sine praevia lege poenali, meaning “No crime, no punishment without a previous penal law” (a principle contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Bangladesh is a member). It seems that Mollah’s fate has been decided. All that remains is making the ICT’s decision consistent with that fate.

After Mollah’s sentencing on 5 February 2013, Shahbag square became the focal point of daily protests calling for the hanging of all Razakars. The Shahbag protests have since died down. However, protests in solidarity with Shahbag have spread across the country, the world, and social media.

On day four of protests, Dr. Imran H Sarker, a key organizer of the protests, outlined the core demands of protestors in the Shahbag Oath: death to Razakars, banning of Jamaat and its student wing (Islami Chhatra Shibir), and boycotting Jamaat-affiliated institutions. Plainly absent from this oath, and the entire Shahbag protests, is any call for fairness within the present process.

Amongst the ranks of the Shahbag protestors are well-educated Bangladeshis, like Sarker – an anesthesiologist and graduate of Dhaka Medical College. Many have even labeled the Shahbag protests a students’ movement, as many of the protest’s most vibrant supporters were born well after the war of independence. From within this liberal minded class, criticism of the ICT and government interference has been a murmur at best.

The calls to ban Jamaat and boycott affiliated institutions reveal the unabashed political ends of Shahbag. Though Jamaat did support Pakistani forces during the revolution, Jamaat is a duly registered political party that engages in the political process. The very nature of a healthy political climate is a nuance spectrum of political ideologies. While the protestors are viewed by many as “perserv[ing] democracy” (to quote India’s President Pranab Mukherjee), ironically, they call for the banning of a legitimate political party.

Since my visit to Bangladesh this past January, the condition of the country has deteriorated drastically. Streets previously teeming with life are now desolate because of recurrent hartals (strikes) and widespread violence. In the interest of containing the current situation, the Government must desist in using the Shahbag protests as a political tool to pressure the ICT. While ostensibly a smart move to gain quick political points, the danger is that in Bangladesh’s tit-for-tat political climate, a future change in government leadership may lead to ugly retaliations. Jamaat has, for its part, asserted that it would support a tribunal that is fair, neutral, and in accordance with international standards.

With the present process engulfed in suspicion and zealous politics, proceeding any further risks pushing the country further into chaos. The injustices of one era cannot rightfully be put to rest through vengeance in another. People will eventually seek justice.

Image Credit: Bisawajit at Bangla Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

More News

From the 1960s to the 1990s, the Danish government implemented the “Spiral Campaign,” a family planning policy that fitted four thousand and five hundred Inuit women and girls—many underage—with intrauterine…

This piece examines the UK government’s proscription of Palestine Action under the Terrorism Act, situating it within a broader trend of shrinking space for public dissent. It argues that the…

This article analyses the distortions of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) notion of proportionality in the context of the Israel-Gaza war. It discusses Israel’s attempts to reinterpret proportionality to justify…