Title: A Brief History of Energy: Where We’ve Come From and Where We’re Going interview with Daniel Yergin

GJIA: Were you heartened by the discussion of energy in the recent U.S. presidential election? What has changed in the rhetoric of politicians as of late?

Yergin:I was quite surprised in the first debate and in the campaign by how much the two candidates were competing to say that one of them was more in favor of natural gas than the other. That is a big change. I think the job aspect – the economic development aspect – of this kind of unconventional gas and oil revolution and what that means for the U.S. economy has changed the political debate on energy in the United States. It was reflected in the presidential campaign, and will be more in the next couple of years. So far 1.7 million jobs are now being supported by this unconventional revolution in shale gas and tight oil.

GJIA: There were some critics of the discussion on energy in the most recent election given that there wasn’t too much talk about climate change with the exception of towards the very end with the onset of Hurricane Sandy. In your writing you have talked a lot about how the concept of peak oil is misguided because human innovation allows us to keep developing new means of production and maintaining high supply levels. In the absence of that oil peak, some people say there is not going to be a push for a transition away from fossil fuels. How can policymakers convince people of the necessity of developing alternate energy sources?

Yergin:We may not have an overarching policy, but we have some key factors. The Renewable Portfolio Standards for utilities that requires a certain percentage of renewables is pretty powerful. The Fuel Efficiency Standards are also pretty powerful too. Those are energy policies, but they are also climate policies. You make a good point that the notion of peak oil ties in very well with concerns about climate change, because it argued that we are running out and must therefore speed up the transition. Part of the argument over shale gas, which is now 37 percent of our gas supply, is that there is a low cost and relatively low carbon option that is going to play a bigger role in our economy.

GJIA: There is an argument floating around that the United States needs to do all it can to reach a state of sovereign energy independence. What you think?

Yergin: We overfocus on energy independence and we miss what is actually going on. We will certainly get less dependent—we will have North America and the Western hemisphere both on the path to be importing a lot less energy from the Eastern hemisphere as these new supplies come on—and at the same time we will become more efficient in how we use energy. After all, U.S. oil output is up 40 percent since 2008. Demographically our use of oil will change as well. We should see North American still importing of oil, just less of it. Part of the recognition that was not there even a year ago is regarding what having these dollars spent in the United States means for the economy, for employment, and for competitiveness. The money stays in this economy rather than going overseas. The domestic supply chain aspects turn out to be more important.

GJIA: Given that we are going to be less dependent and the projections continue to show that the United States is going to be relying less on oil and gas from the Middle East, do you think that this new energy position will cause a rethink of U.S. foreign policy away from the Middle East? Are we going to see a U.S. pullback from the region?

Yergin: In the next few years as we argue about budgets in the United States that will probably factor, but the biggest issue right now is Iran’s nuclear weapons – that is not really about oil supply. I think the United States will continue to have a deep interest in what happens in the Middle East because of its centrality. Other states like China are now getting more oil from the Persian Gulf than we do, and how Chinese interests and their view of energy evolves will be very important. It was interesting for me in publishing The Quest in China to listen to the discussion there about energy. Some people postulate there is an inevitable clash with the United States just as there are some people here who think there is an inevitable clash, but there are a lot of other people who see this more in terms of commercial competition, and that is not the same as geopolitical rivalry. These two economies are tied together in so many ways. To become convinced that there has to be a clash is not a good way to think about things. It could happen, but there are a lot of reasons it should not happen. That said, it is important that both countries make sure they understand each other’s energy positions and energy needs. The more commercial and the less geopolitical the relationship, the better.

GJIA: In your books you tend to draw out the narrative and delve into individual perspectives on issues in addition to depicting the overarching positions of nations. How much agency do you think individual actors at the upper levels have in influencing this energy dialogue and the way that these nations interact with one another, and how much of it do you think is based off of the pure economics?

Yergin: I think people do matter. National mindsets are comprised of a mixture of the views of different people and groups. Take interest groups, for example. Some Chinese have said that the comments made about the South China Sea being a core interest by other Chinese were not authorized statements. Individuals do matter, particularly when situations are fluid. This also has to be seen in the overall context of the U.S.-China relationship. I think the balance of the relationship changed with the financial crisis. China’s rebound was early and critical for global recovery.

GJIA: The subject of the feasibility of nuclear power has come up time and time again, especially given the current catastrophes. Is this backlash going to be sustained, or is it just temporary?

Yergin: In Germany it depends on how well they do in terms of substituting other things, such as gas from Russia and offshore wind – how their grid system reacts will also have a big impact. I was just in Japan and spent a lot of time talking to the Japanese about this issue. The former government had not so much said it was going to eliminate nuclear power. They have said that they want to develop their capabilities so that they have the option to eliminate nuclear power, which is one step removed. What happened in Fukushima was horrible – an accident that should not have happened. They are looking at what went wrong, such as why they did not have a proper regulatory system to separate safety regulation from promotion, and putting safety first going forward. They also want to take a look at the competitiveness of Japanese industry and what happens if they don’t have cheap base load nuclear energy. Their energy security policy is based upon energy diversification, but they have a more challenging time on renewables than Germany does. This is a debate that’s going to continue, but obviously Fukushima has deeply scarred the Japanese polity. The new Abe government has already signaled that it will likely take a different tack and by the summer may well lay out a continuing role for nuclear power in Japan’s energy mix.

GJIA: The past year has seen major opposition to President Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency, and there are indications that there is infighting in the Russian elite. Some suggest that part of this opposition stems from the Russian economy slowing down and Europe becoming less reliant on Russian natural gas. Do you think this opposition really is based on that, or is it more of an anti-authoritarian sentiment?

Yergin:I think it represents a lot of different interests. The anti-Putin movement certainly would not have existed before. The issue before the government now is one of modernization and reform-making the economy more competitive and ensuring that Russia is not a petro-state. There is no denying that Russia is a state that is very dependent upon oil and gas revenues; it has a comparative advantage there. The question is: what does that do in terms of stifling innovation in other parts of economy? I think that is the debate within the Russian elite. Russia is still a heavyweight player in terms of energy. It is interesting, though, that the United States has now overtaken Russia as the world’s largest natural gas producer. There is also a contest now going on between Brussels and Moscow over how the European gas markets will be organized and how prices should be set. That is another very critical issue for the Russians, but both sides are currently digging their heels.

GJIA: We had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Fatih Birol from the International Energy Agency about his new predictions for Iraq’s future in terms of being an energy-exporting nation. How do you think that will affect the geopolitics of pipelines?

Yergin: How fast Iraqi oil grows depends on maybe three things. One is political stability in Iraq. Two is the economic terms – are the fiscal terms attractive? And three is their ability to deal with logistics and scale. What we see now is the movement of companies into Kurdistan. The terms are more attractive, it is easier to work there, and it is more secure. Pipelines are still very crucial because you still need to evacu- ate the oil. The CEO of one company told me how he looks at Kurdistan and it reminds him of what Texas in the 1920s must have been like with its huge potential. In The Quest I have a story that I heard from the Kurdish oil minister. When politicians were divvying things up in Baghdad, they said that there was no oil in the mountains of Kurdistan. He said, “If that is the case, just give them to us.” That area had not been developed under Saddam for ethnic and political reasons. Iraq has the potential to become a major source of loose supplies for the market, but only if the country can deal with those issues, particularly the security and sta- bility issue.

GJIA: Given the changes of government in Iraq and Libya, another major producer of oil, it seems like there is an opportunity for more pro-Western governments to have a greater influence in the oil markets. Is the United States in a stronger position than it was a few years ago?

Yergin:No. Those countries are not major sources of supplies for the United States. This question of what these governments are going to be like – their ability to maintain cohesion and maintain their position – is still up in the air. There are still a lot of challenges. Libya, in some ways, has it easier because it has a small population with a lot of money coming in. On the other hand, under Muammar Gaddafi it did not have any institutions. There is still a question of who is going to be in charge of these countries in five years. Things were frozen in these countries for three decades or more, and now there is been an upending of the strategic balance. Is the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt going to be able to bring in the foreign investment, bring back tourism, manage the economy, get growth going, and meet expectations? Another element will be the battle within the Muslim Brotherhood. So I think the future will be more turbulent.

GJIA: The past two years have seen some of the toughest sanctions levied against Iranian oil. Some say that China will step in to fill that vacuum. Do you see that as a potential source for conflict between the United States and China?

Yergin: I think the Iranian sanctions have worked better than had been anticipated a year ago. This is partly because of very effective diplomacy, with Europe and the United States working together on this, and it is also because new supplies have come into the market, such as from the Saudis, and from Iraq. I think this would not have worked without the buildup of U.S. production as well – that 40 percent increase since 2008. So countries have been willing to go along with the United States because the costs of not going along are high, and they have been able to access these alternate supplies. Iran still has to decide whether it wants to come to the negotiating table. At the end of the day, it is not just about the Iranian sanctions working, but also about whether the sanctions affect the choices that Iran makes. There will be reluctance to give up the sanctions until there is concrete action. The Iranian approach will be to say, “Give up the sanctions and let’s negotiate.” The next thing to look for will be to see whether the next round of negotiations between Iran and the United States are serious – and whether they take place.

GJIA: There is a lot of talk regarding the diversification of both energy possibilities and technology options for extraction. Is this trend towards entropy going to shift balance of power that currently exists between the inter- connected economies of the world and bring about a more chaotic, multi-polar system?

Yergin: Energy diversification enhances energy security. As Churchill said, “Variety and variety alone.” We are going to see a lot of new gas supplies coming from places like East Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. These will be new opportunities. There is also room for new political contro- versy, such as how these East African countries develop institutions to be ready for very large-scale development. Additionally, the United States being an energy exporter is big. The United States was once an exporter. During World War II, out of every seven barrels of oil that the Allies used, six came from the United States, but we got out of the energy exporting business as a country a long time ago. The natu- ral gas market in the United States is limited not by supply, but by demand. I think the United States as a modest exporter of LNG will be a contributor to stability. That possibility is certainly a surprise from what was anticipated half a decade ago!

Daniel Yergin was interviewed by William Handel.

Daniel Yergin is vice chairman of IHS and founder of Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA). He received the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Prize.

Image Credit: ENERGY.GOV, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

More News

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

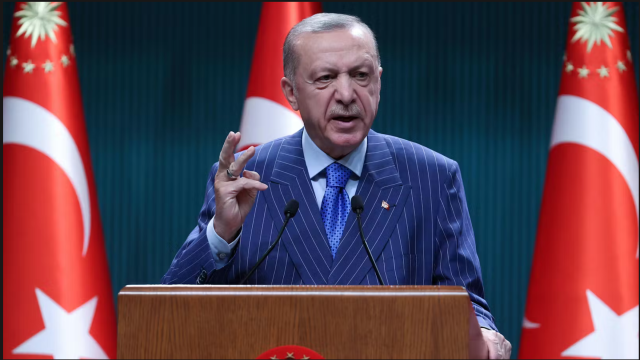

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…