Title: American Power at Home and Abroad: Success, Failures, and Challenges

Click here to view as PDF || Shop the Entire Current Issue- The Future of Energy || Return to The Future of Energy index

In the midst of dynamic geopolitical shifts since President Obama’s first term, former National Security Advisor General James Jones (USMC, ret.) offers insights into the successes, failures, and future challenges for U.S. foreign policy and national security in the 21st Century. General Jones reflects on the role of the National Security Council in the Obama Administration, the fate of Afghanistan after 2014, the future of NATO, and the “pivot” to the Asia-Pacific region in this wide-ranging interview with the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

GJIA: Looking back over your time as National Security Advisor, what do you consider to be the greatest triumph of the policy you helped craft? What is your biggest regret in retrospect?

Jones: Well, one of the significant steps forward was the reorganization of the National Security Council– bringing the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Council together under the umbrella of a coordinated National Security Staff. Without question, this step was transformational. It was not my doing alone; there was con- sensus that it was the right thing to do. I think it has helped the President to make national and international security decisions much more quickly, and with greater fidelity in terms of the information he was getting. That would be the near-term success. The long-term one, I think, is the START Treaty with the Russians. So those are both positives.

I would cite the following two largest disappointments: announcing that Guantanamo Bay was going to close without full appreciation of the obstacles and a concept of how we would overcome them. It turned out the ‘not in my backyard’ syndrome was alive and well in all the states, and so Guantanamo Bay was not closed. Secondly, at least from my standpoint, is Pakistan’s double-dealing in its bilateral relationship with us. There are other disappointments as well. We didn’t reenergize the Palestinian-Israeli peace talks and Iran is still a threat. That said, the biggest disappointment was the deception perpetrated at high levels in the Pakistani military, including the existence of terrorist safe havens and the whereabouts of Usama bin Laden, at a time when I thought we had some- thing that was going to be good and positively affect the future of Afghani- stan and Pakistan. This deception was very unfortunate.

GJIA: There has been quite a bit of debate about the role that the National Security Staff plays in acting as a foreign policy arm of the United States in relation to other entities like the Department of Defense or State Department. What do you think the proper role should be?

Jones: The fact is that in this highly complex and integrated world there are so many issues, and such a wide spectrum of issues at play in national security that you need an overarching mechanism that drives the gears of gov- ernment in a coordinated fashion. My view is that in support of the President, the National Security Council basically keeps the really big and pressing issues visible and prioritized. The President’s interests in these strategically important issues force the interagency to coalesce around the table. One of the advantages of our system is that President Obama really wants dialogue and debate, and the biggest sin that one can commit in the White House is to exclude someone who has equity in a particular issue from the debate.

It was our job at the NSC to make sure that all of the stakeholders were seated at the table and had a chance to articulate their views and opinions. You have never seen an article in a newspaper by a disgruntled, former senior member of the administration who said, “I was never consulted.” It just has not happened. That is why the NSC is important, and people who do not under- stand that nuance tend to criticize the NSC for being power-grabbing. That is not the case. The NSC directs and orchestrates a wide-ranging debate from all of the points of view on every issue. It does not impose its will on them. That is fundamentally the President’s policy; before he makes a decision he wants a bottom-up review that stimulates debate, identifies tensions, and provides for discussion until we’ve exhausted relevant data and points of view and he has enough information to make a decision. So it’s a nuance. People outside the system—and they don’t have to be too far outside the system to criticize it—tend to levy a false criticism that overlooks the role of the NSC and the procedures that make it work.

GJIA: What do you see now, going forward, as the greatest threat the United States faces in terms of national security?

Jones: I agree with Admiral Michael Mullen who testified to Congress that the greatest threat is our massive fiscal imbalance, or more broadly the failure to repair our economy. The greatest threat is internal, not external.

GJIA: Given how events are currently playing out in Afghanistan, do you believe that the strategic decision to implement a counterinsurgency-focused strategy has been successful? How do you see the role of the United States after the mission-transition in 2014?

Jones: My feeling is that there comes a time in every conflict when you have to begin to see the endgame, otherwise the country is mired in an open-ended affair. I think the decision to augment the force was a good one, even though it was a surprise to many. If you recall, we changed commanders, and the new commander, General Stanley McChrystal, made a thorough assess- ment and decided things were not as good as the previous commander had assessed. General McChrystal said that he wanted 40,000 more troops. We constituted that increase with 30,000 US troops and 10,000 NATO troops. There is no question that the introduction of 30,000 US troops is going to make a difference whenever and wherever deployed. The question becomes “is it a game-changing difference in terms of the outcome of the conflict?”, and I think that is still an open ques- tion. One of the reasons for this is the weakness of President Hamid Karzai. It’s a leadership problem. He has scarcely grown or evolved since the first day he took office in his first term. He is, in my view, a disappointment. Secondly, the failure of Pakistan to decide to get on board and fight the terrorist network, and instead doing its best to sow disarray, materially jeopardizes the future. It’s hard to predict the outcome in this situation, but I’m not optimistic.

GJIA: Given that NATO forces in Afghanistan have been fighting for almost 9 years, what do you think the lesson of Afghanistan should be for NATO and the United States?

Jones: The lesson of Afghanistan is the same lesson that we learned in Viet- nam. If the people do not want what you are selling, there is no amount of cajoling that is going to make them think otherwise. Fundamentally, the trick is that if you are ever going to land any combat soldier on the ground in any particular country because you are hoping to change the government and way people want to live, you better make sure that they want that change and that they are willing to commit something to it. This is why the 2014 date for Afghanistan does not bother me; because we have been there long enough, we have offered enough. We have paid with blood and treasure, and if they still don’t want it—if Karzai can’t lead his people—then they do not deserve it. I am sick and tired of reading about Afghans killing Americans or members of the international force who are trying to help them. When I was 23 years old, I returned from Vietnam with the impression that if the North ever confronted the South Vietnamese army, the army would fail due to a lack of passion for freedom and liberty (something that we as Americans feel instinctively).

GJIA: Do you have similar impressions with the current Afghan security force as you did coming out of Vietnam?

Jones: Absolutely. The Karzai government has had nine years to try to convince the Afghans that this is the way to the future—that what the international community is offering is the right path—and if they do not want it, we cannot force it on them. So whatev- er the relationship is in 2014—whether we transition to economic mentoring and training or not—it has to be what the Afghans want. We cannot forcibly impose reform, particular values, or democracy on the Afghans if they don’t embrace it.

GJIA: What do you see as the changing nature of NATO going forward, and what can and should the United States expect out of the alliance?

Jones: It is extremely important to maintain the ties and relationships we have, but I do not think we need the post-World War II global footprint in Europe with the huge bases and everything else. We could maintain a strong personnel presence on the continent through the use of rotational assignments and focus on reductions to force installations. The Europeans should assume a larger role and responsibility for their own safety and security, and I think NATO can be transformed towards that end. One of the great gifts of the twentieth century is that countries all over the world want to have a relationship with the United States Armed Forces, and they pattern their tactics and procedures based on our model. Maintaining that connection and influence serves our interests. NATO needs to change and transform accordingly, and it is showing some capacity to do that.

Along with transforming NATO to meet the needs of the modern security environment, we need to pay heed to the African continent, which I regard as a vital economic battle space in which we need to compete strongly. Succeed- ing in the 21st century requires more than outstanding security forces. We need a more holistic global engagement strategy that harnesses the capabilities of our public sector, our private sector, and our NGOs to gain influence and effect positive outcomes abroad. It comes down to whether the United States wants to remain a global power and nation of significance. I think our people would answer that question with a resounding ‘yes,’ and I certainly think that most countries around the world would answer in the affirmative as well. Most do not want to see the world without a strong and influential United States. Other countries will certainly play an increasingly influen- tial role in world affairs, but the United States must not shrink from its role on the world stage. The fact is that people, even some of our harshest critics, get very nervous when we are absent.

To be relevant and effective today and in the future, I don’t think NATO can continue to be simply a reac- tive alliance. NATO was based on the idea of massive retaliation and mutually assured destruction that defined the stalemate of the Cold War. I think NATO’s success will depend upon whether or not it can transition from a reactive alliance to a proactive alliance. I don’t mean that NATO’s proactive role is necessarily a kinetic one, but NATO can project influence and accomplish much good by helping developing countries in Africa and elsewhere to learn how to defend themselves, train their own forces, and foster economic and humanitarian progress that is the true basis for sustainable security. This is vital in the fight against terrorism because if you do good things for people that people can see and feel, it does not matter what the mullahs tell them about the evils of the West; they will see that it is not true. And so I think NATO has much more of a proactive, non-threatening, non-combat type role to play, but it must always be ready to shift from one role to the other when its military might is needed.

GJIA: What do you think the proper role of the United States should be in the wake of the Arab Awakening?

Jones: With respect to Syria, the United States cannot just sit back and hide behind the fact that the UN is not involving itself. There are many instances in history when we have said, “OK, you won’t do it, we’ll do it.” I’m not saying that means we must under- take unilateral action. I think what is required of us is to work with moder- ate Arabs and Europeans to fashion a coalition of the willing to show the next generation of Syrian leaders—whoever they are—that we offer help for a better future. I think we should be doing more in terms of humanitarian outreach and helping to hasten the departure of President Bashar al-Assad. We should be working overtime to determine who is likely to replace Assad and assist those who offer a hopeful, modern vision for a free and responsible Syria. If we do nothing, I can guarantee that Assad will be replaced by a radical element. If we do the little things—if we do the humanitarian outreach, we undertake the engagement, and we help the Syrians free themselves from this tyrant who has been massacring his own people—then we have a better chance for a good outcome in Syria going forward. A positive transition in Syria would be a tremendous blow to Iran, and a very positive development for regional security and the security of Israel.

GJIA: What do you see as the strategic goals of the United States in staying an influential player in the Asia-Pacific region in light of the stated ‘pivot’ to the region?

Jones: The United States has been an Asia-Pacific power since World War II, so I think that having to re-state that was not necessary. We should not present the United States as an intrud- ing nation; we have been present in the region for a long time. We have great allies such as the Koreans, the Australians, and the Japanese, among others. We have enormous interests in the success and stability of Taiwan. We have established roots in the region, so the “Asian pivot” should really be economic more than anything else. We have always had a military presence in the region. We might juggle things around a little, but to me it was an unfortunate and unnecessary choice of words because when you pivot towards something that means you are pivoting away from something else– and I think it sent an unintentional message to our friends and allies in other parts of the world.

James Jones was interviewed by William Handel and Christian Chung on 9 September 2012.

James L. Jones, USMC (Ret.), is founder and President of Jones Group International. He has previously served as National Security Advisor to President Barack Obama; President and CEO of the U.S. Chamber Institute for 21st Century Energy; Commandant of the United States Marine Corps; Supreme Allied Commander, Europe; and Commander, US European Command.

Image Credit: Pete Souza, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct

More News

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

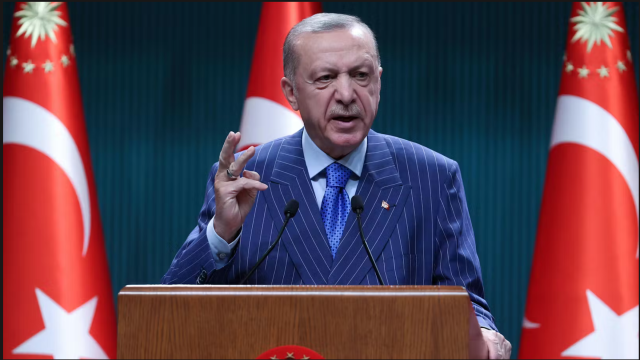

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…