The Obama administration’s landmark new approach to countering violent extremism through engaging community partners calls for no less than a paradigm shift in how we understand the causes of terrorism. The shift is away from a pathways approach focused on how push and pull factors influenced one person’s trajectory toward or away from violent extremism, and towards an ecological view that looks at how characteristics of the social environment can either lead to or diminish involvement in violent extremism for the persons living there.

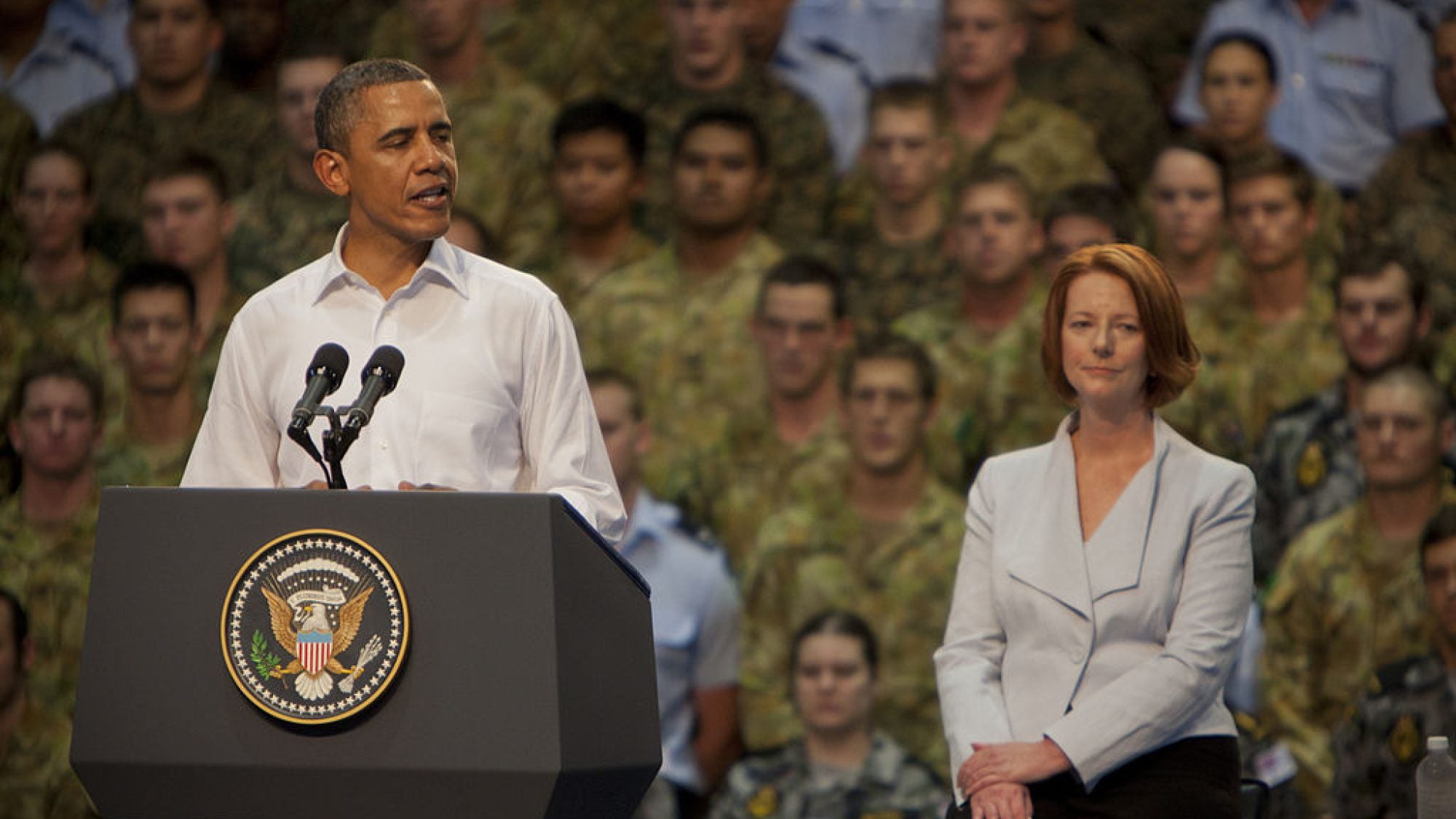

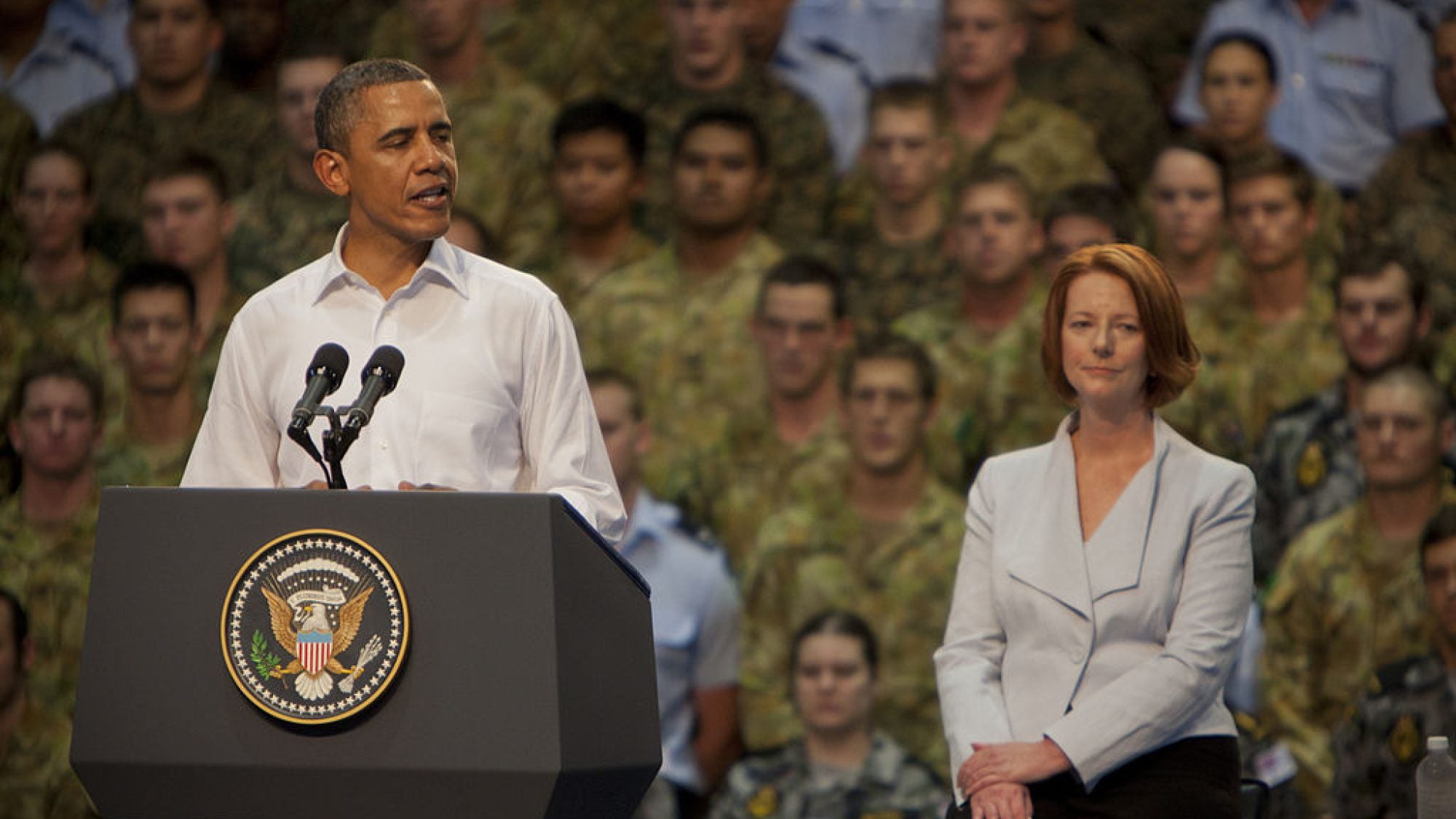

The core idea of this new paradigm, conveyed in the White House’s December 2011 Strategic Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States (SIP), is that of countering violent extremism through building resilience. Denis McDonough, former Deputy National Security Advisor to President Obama, expressed this at an Islamic center in Virginia, stating, “we know, as the President said, that the best defense against terrorist ideologies is strong and resilient individuals and communities.” Subsequent White House documents have further unpacked this, for example, in stating: “[n]ational security draws on the strength and resilience of our citizens, communities, and economy.”

Resilience usually refers to persons’ capacities to withstand or bounce back from adversity. It is a concept derived from engineering perspectives upon the durability of materials to bend and not break. In recent years, resilience has come to the forefront in the fields of public health, child development, and disaster relief. To scientists and policymakers, resilience is not just a property of individuals, but of families, communities, organizations, networks, and societies. Resilience-focused policies and interventions that support or enhance its components have yielded significant and cost effective gains in preventing HIV/AIDS transmission, and helping high-risk children and disaster-impacted populations. Though the present use of resilience sounds more like resistance, today’s hope is that such approaches could also keep young Americans away from violent extremism.

A resilience approach offers no quick fix, not in any of the aforementioned fields or in countering violent extremism. It depends upon adequately understanding what resilience means for a particular group of persons and how it has been shaped by history, politics, social context, and culture. It also depends upon government establishing and sustaining partnerships with the impacted families, communities, networks, and organizations. Additionally, it depends on government working in partnership to design, implement, and evaluate what interventions can really make a difference in building resilience, a process certain to involve trial and error… (purchase article…)

Stevan Weine is Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the International Center on Responses to Catastrophes at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He leads a federally supported program of research on refugees and migrants, and has received two NIH career scientist awards. Weine is author of When History is a Nightmare: Lives and Memories of Ethnic Cleansing in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Rutgers, 1999) and Testimony and Catastrophe: Narrating the Traumas of Political Violence (Northwestern, 2006).

Image Credit: Sgt Pete Thibodeau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.