Title: For Refugee Protection, More Lenient Marriage Recognition is a Must

As of late September 2013, two million refugees have fled the civil war in Syria—mostly into neighboring Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq—and thousands are expected to temporarily or permanently resettle in Sweden, Germany, the United States, and other Western nations. Factoring heavily into resettlement countries’ admission selections are refugees’ family relationships, as rights to family unity and family reunification are important under international law.

Out of the 58,179 total refugees admitted in the United States in 2012, most were not the principal applicants for admission but rather their spouses and unmarried children under 21. When the host countries assess applications and determine family relationships, they assess the validity of the refugees’ marriages. Within the United States, law dictates that children born in wedlock stand a better chance of deriving immigration benefits from their parents, especially from their father.

The application of ordinary rules for foreign marriage recognition could be problematic for refugees, depending on each resettlement country. Within the overall legal framework, the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees addresses the personal eligibility for marriage by applying the law of the country of domicile (permanent residence) as opposed to the law of the country of nationality that prevails in countries such as Germany and Sweden. However, in terms of the validity of marriage formalities, the treaty leaves broad authority to domicile and host countries, most of which are likely to apply the law of the place of marriage celebration as a general rule.

Strict applications of the law of the place of marriage celebration are likely to impose an unreasonable burden on many refugees while unjustly subjecting others to unequal treatment. On the one hand, in cases where the marriage is celebrated in a refugee’s country of nationality, he or she is likely to lack access to official marriage records for reasons related to his or her status, either because of fear of persecution by the same government officials who have custody of the records or because of the country’s devastation. Refugees from Burma—who accounted for 24 percent of U.S. refugee flows in 2012—and from similar places might have no option to register their marriage in the first place.

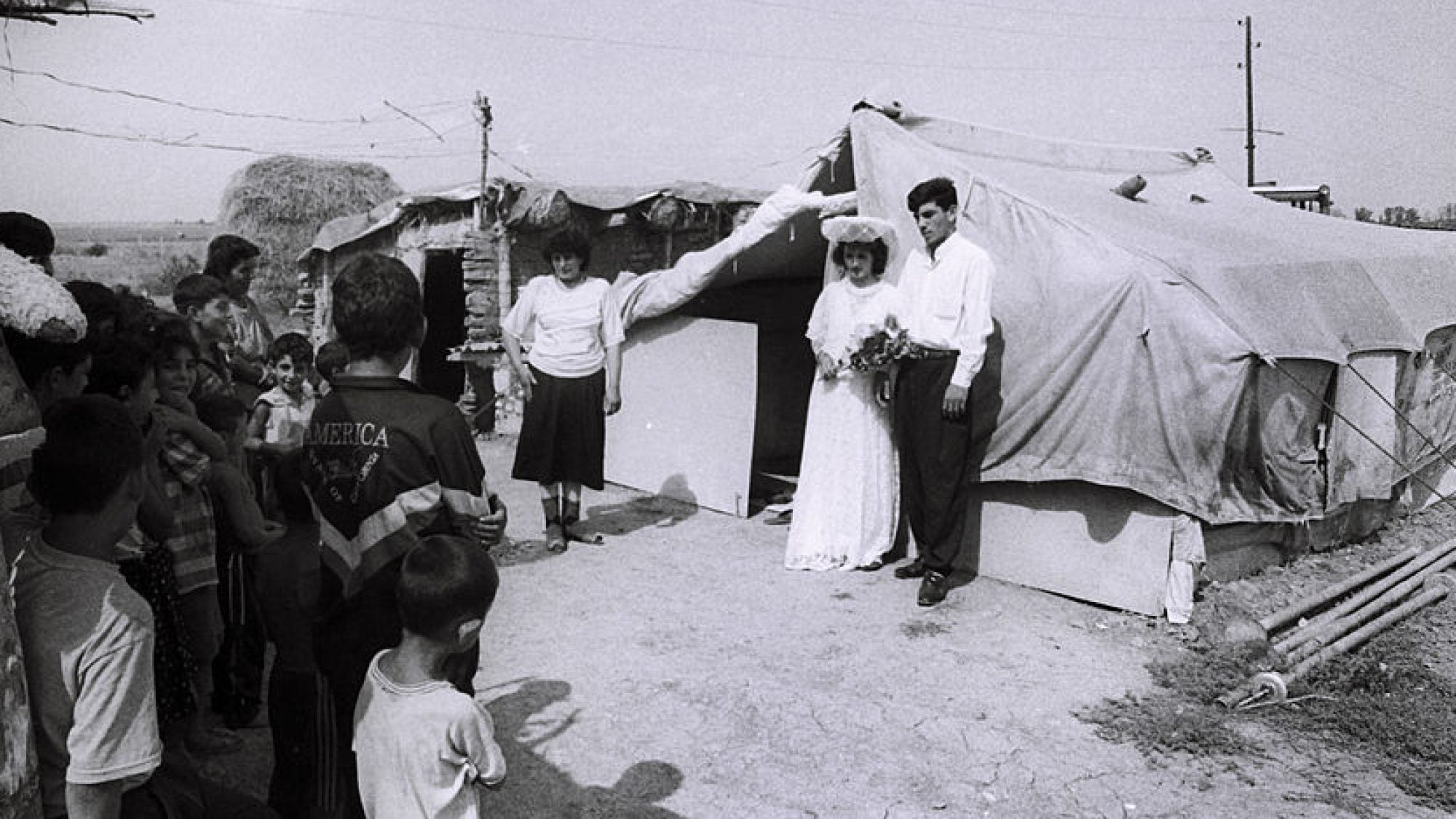

On the other hand, in cases where the marriage is celebrated in a temporary host country, many practical barriers—including lack of knowledge, financial means, transportation, language barriers, and discrimination—are likely to hinder refugees’ compliance with local laws regarding marriage formalities. Refugees often celebrate marriages in refugee camps, in accordance with their home customs and traditions; however, their customs and traditions might not be recognized under host country laws. For example, consider two separate Liberian refugee couples contemplating a customary marriage—one living in a refugee camp in Ghana, the other living in a refugee camp in Côte d’Ivoire, a decade ago. At the time, Liberia recognized customary marriages, somewhat broadly defined as marriages “between a man and a woman performed according to the tribal tradition of their locality;” however, the country’s marriage registration requirements were either inexistent or, due to the ongoing civil war, impracticable. Meanwhile, Ghana also recognized customary marriages, albeit in narrower terms as marriages celebrated according to customary laws applicable to “particular communities in Ghana,” and marriage registration was available but not mandatory for any qualifying couple. In contrast, Côte d’Ivoire did not (and still does not) recognize customary marriages under any circumstance. Even though both marriages would have been equally valid in Liberia, only the refugee couple in Ghana could have obtained a local marriage certificate (at least under a very generous interpretation of Ghanaian law), while the refugee couple in Côte d’Ivoire certainly could not, solely based on an incidental difference in places of temporary settlement.

This is a particularly cruel and unjust system considering that refugees by definition have little choice over their initial settlement location; unlike voluntary migrants, they flee their country for another due to forces beyond their control. Circumstances of refugees’ respective host countries should not have the power to determine their subsequent rights to family support, which is crucial to their recovery from the trauma of war and exile.

In the long-term, the ideal solution would be amending the 1951 Convention to allow refugees themselves to choose between the law of their country of nationality and the law of their host country in satisfying marriage formality requirements. In the short-term, countries such as the United States should enact new legislation or issue new executive rules and regulations to the same effect. Refugees should no longer be required to present proof of marriage registration unless both their country of nationality and their host country require it. They should be able more often to rely on secondary evidence, such as affidavits written by friends and other family members, to prove the existence of their marriage.

Refugee families need special protection. Their rights should be left neither to the arbitrary inconsistencies of the international system nor to the informal guidance and discretion of individual immigration officers.

Image Credit:Ilgar Jafarov, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

More News

We in the United States have long held one narrative of the Middle East—one of political instability, sectarian unrest, and oligarchs protecting great wealth in the hands of way too…

When the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs launched this online edition, I suggested that it address “human rights and human dignity.” Why dignity? As Anthony Clark Arend and I explore…

Georgetown professor Matthew Kroenig sat down with the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs to discuss his attendance at a recent meeting with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in New York.