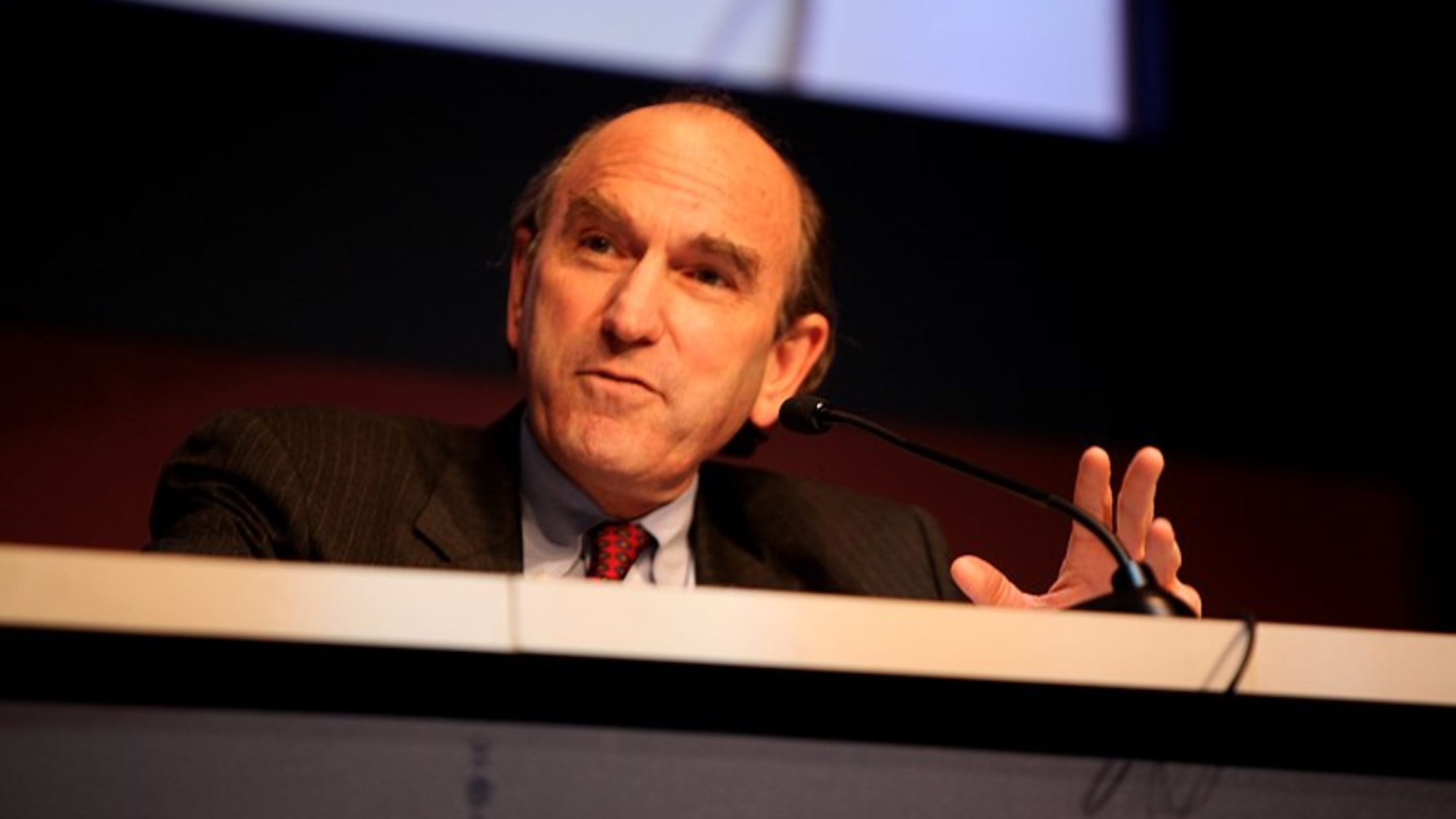

Title: U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East with Elliott Abrams

At Georgetown University’s Andrew H. Siegal Memorial Inaugural Lecture, Five Minutes with an Expert sat down with American diplomat Elliott Abrams to discuss the implications of his recent book, Realism and Democracy: American Foreign Policy After the Arab Spring.

GJIA: You have experience serving in many different administrations over the years. What changes have you seen in U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East?

EA: The general high priority doesn’t change, and there’s been no real pivot to Asia. The major change is the effort – to some extent by Obama and the Trump administration – to dig us out after the wars in Afghanistan and particularly Iraq. The Obama administration, for example, had a very different policy toward Iraq than its predecessor. Bush got in and Obama essentially got out, and now [under the Trump administration] we’re back in a small way. Most of the main pieces of American policy in the Middle East remain a priority: the alliances with Israel, Jordan, Egypt, the Gulf countries and, at least since 1979, the huge problem of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Given these trends, what do you believe the course of American policy should be moving forward?

We’ve got two huge problems that we have to try to handle. One of them is Islamic extremism of the ISIS or al-Qaeda variety, which has been a problem for decades. The other is Iran and the growing power and influence of the Islamic Republic with its greater intervention in the region and its nuclear weapons program.

What I argue in my book is that the temptation to say, “We don’t have time for things like democracy and human rights—we have real problems like security issues that we need to deal with,” is really a mistake, because some of our allies—the ones that fell like Mubarak and the others too, that saw uprisings—were not stable because they were not legitimate rulers. I don’t think that backing illegitimate rulers is a formula for stability; It’s certainly not a formula for democracy or human rights. And I argue that when we’re talking about Islamic extremism, we’ve got to recognize that it is a set of ideas. It is a set of ideas that tell you what legitimate government should look like, what good government should look like, how you should lead your life properly.

There is a debate in Muslim societies, including Arab societies, over whether the Islamic view is correct or incorrect. I don’t think policemen and soldiers can win that debate. They can suppress the debate, they can jail a lot of people and they can kill a lot of people, but that does not persuade people that different ideas are better. For that, you need politics. You need to persuade people, which is much easier in a democracy. I am making the argument [in my book] that if you want stability in the Middle East in the long run, you need to open the political systems up so there can be this debate.

Pragmatically, what do you think is hindering American realization that we need to change our foreign policy in the Middle East?

First, the Arab Spring gave rise to tremendous optimism that was then crushed because, except in Tunisia, these uprisings failed. So they’ve given way to a kind of pessimism and fatigue.

And there has always been bigotry that exists that Islam is incompatible with democracy. Or, maybe Islam isn’t, but Arab culture is. I think Arab culture is a real obstacle for democracy for many reasons, treatment of women being one of them.

So I am not surprised that after this [bigotry], and particularly after the Iraq war and the challenge of Jihadis, what a lot of people say is, “Look, let’s be realistic. These are nice dreams to have [that the Middle East will become democratic] and maybe someday, but now we have a real security problem. Now we have somebody like General Sisi who is our ally, who is going to take on the problem—so let’s just work with him and forget about the other stuff.”

My argument is that what people call realism—realpolitik—I don’t think it’s very realistic.

If an uprising like the Arab Spring wasn’t able to spark a change in the U.S. political mindset, who or what do you think would be able to spark that change?

I need to be careful when I speak about this, but we’re never going to bring democracy to the Middle East. Only the Middle East can do that. This is going to be up to the people of the region. I would like us, at least, not to make it harder for them to achieve democracy and respect for human rights.

And as [countries in the Middle East] make more progress, I think there will be more support [for them from the United States]. If you go up to Congress now and you say, “I’d like to argue for more support for Tunisia,” you will get a hearing and you will get votes. Because people say, “Tunisia? What they’re doing is perfect and we want to help.”

Success breeds success. It’s going to take more progress on the ground in the Middle East to reawaken that optimism in the United States.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

. . .

Elliott Abrams is a Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, D.C. He served in the Reagan administration as Assistant Secretary of State, and he served as Deputy Assistant to the President and Deputy National Security Advisor under George W. Bush, where he supervised U.S. policy in the Middle East for the White House. He is a member of the board of the National Endowment for Democracy and teaches U.S. foreign policy at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. He is the author of five books, including, most recently, Realism and Democracy: American Foreign Policy After the Arab Spring.