Title: China’s Space Station: Persistence Pays Off

With the launch of Tianhe-1 – the core module of its planned space station – China will bring to fruition its human spaceflight plans that have been in motion since 1992. Though the launch is planned for some time in 2019, that date could easily be pushed back. Speed, however, has not been a Chinese concern. Whereas the United States was heroically able to send men to the moon and return them safely within ten years of the announced intention to do so, it has since struggled with the necessary political will to continue human spaceflight exploration ever since. China’s human spaceflight program, on the other hand, has advanced more slowly, taking the time to build political support as well as on-the-ground and in-space infrastructure, to continue at a much more steady, consistent pace. That consistency demonstrates the value of persistence over speed for space development and exploration – as well as the strategic benefits to be reaped from both – through its efforts to both incorporate lessons from and avoid the mistakes associated with the human space program executed by the United States during the Cold War.

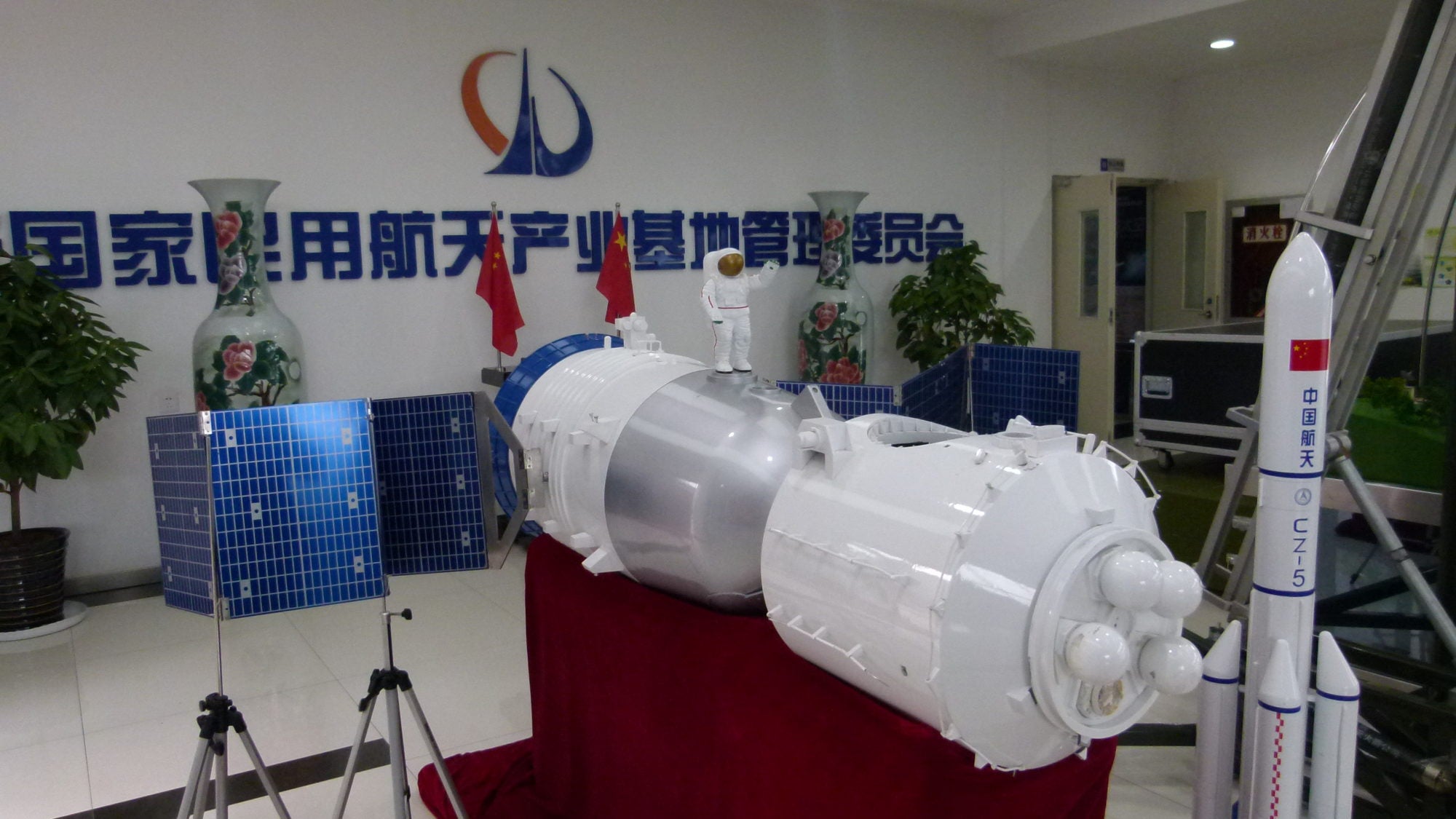

China launched Project 921 in 1992 as a three-stage program working toward human spaceflight. The first step involved a display of capability using the Shenzhou “Heavenly Vessel” capsule. In 2003, the Shenzhou5 mission carried China’s first astronaut, or taikonaut, Yang Liwei, into orbit. The mission designated China as the third country to possess independent human spaceflight capacity. The second step has focused on the development and testing of more advanced competencies, such as docking, maneuvering, and long-term life support. As part of such goals, China placed several temporary, small space stations, known as the Tiangong

“Heavenly Palace” laboratories, into orbit as technological testbeds. The program is expected to culminate in a third and final stage – assembly and habitation of a large space station – which is expected to have a mass of about 80-100 metric tons. That China has remained focused on the objectives of Project 921 for over 25 years demonstrates patience, political will, and the ability to execute a long-term program.

Parallel to Project 921, China has also been developing the heavy-lift launch vehicle needed to send the Tianhe modules into orbit or for interplanetary travel. Called the Long March 5, it suffered numerous delays before its maiden launch in 2016, and experienced a launch failure in 2017. Future tests will play a key role in determining the Tianhe timetable.

Additionally, China currently operates a robotic lunar exploration program, named Chang’e after the Chinese Moon goddess. The program has included the operation of a robotic lander and a remotely-controlled rover – zoomorphized as Yutu the rabbit – that roamed the lunar surface from 2013 to 2016. To the delight of Chinese observers, the rover’s journey included a feared “death” and eventual recovery.

The capabilities of the Shenzhou, Chang’e, and Long March 5 programs could be combined into a manned Chinese lunar program sometime in the not-too-distant future. Chinese space advocates have studied and learned well the lessons of the U.S. Apollo program and have used these to “sell” space efforts to China’s leadership and the Chinese public. The first lesson was to attach space efforts to a long-term strategic goal that did not involve international relations. Whereas U.S. exploration efforts floundered after the Cold War-era motivation faded, Chinese space endeavors have consistently been presented as a part of a more comprehensive strategy for economic development within China. Economic development is tied to strategic security, so Chinese government support for space activity is unlikely to diminish in importance.

The second lesson learned from U.S. space development efforts was that there are many benefits to spaceflight capacity, and all should be fully exploited. The benefits that the United States reaped from the Apollo program ranged from an increase in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) students, to employing space technology for other uses, to the military applications of the dual-use technology inherently developed as part of space exploration efforts. Similarly, China has sought and has reaped benefits in each of these areas.

U.S. security communities are primarily focused on the ways in which the Chinese military gains from spaceflight. Technology is described as “dual use” when it benefits both military and civil sectors. When dual use technology is employed by the military, it is often difficult to tell whether the intended purpose of the technology is offensive or defensive. Within the realm of space exploration, anti-satellite technology could be designated as dual use, as it is similar to missile defense technology. In 2007, China demonstrated its interest in dual use, anti-satellite technology with a kinetic test that created a large and dangerous debris field. Moreover, beyond the development of specific hardware, spaceflight has required China to increase its skills in areas like computational analysis, which is valuable to both the civil and military sectors.

In terms of economic benefits, global perceptions of China’s manufacturing capabilities have changed favorably as a consequence of its space achievements. While a space race between the United States and China has often been suggested, such a race is one in which the former should have no interest in competing, since China is still only repeating what the United States accomplished decades ago. The real race currently revolves around technology development in a broader sense. As part of this new competition, China is using space as one avenue to gain the upper hand.

The third lesson learned from the Apollo program was that it served as just as much of a tool of the Cold War as any tank or gun. It constituted a way to show the world, especially non-aligned countries, that they ought to side with the West, since the United States had demonstrated itself to be the leader in global technology. The benefits of space capacity for a state’s strategic influence are just as important as any other advantage.

China has demonstrated its awareness of this reality by making it known that it will welcome guests to its space station. Whether that invitation will extend to the United States is unclear, as the latter has actively blocked China from participating in the U.S.-led International Space Station (ISS). The deliberate steps that China has taken to attract external space partnerships in the area of space science further indicate its attention to strategic considerations. China recently constructed the largest radio telescope in the world and launched a space mission – the first of its kind – to search for dark matter. Scientists from around the globe, driven by goals that are dictated by nature rather than politics, will be anxious to share in the data gathering and analysis made possible by these Chinese projects.

The history of U.S. space exploration has largely been characterized by short-term investment and goals. While the United States was able to reach and return from the moon less than a decade after the decision to do so had been made, it did not leave any infrastructure to make future trips financially and technically more feasible. When U.S. astronauts first landed on the Moon in 1969, they looked around, planted a flag, and returned home. Though a few more lunar voyages were completed in subsequent years, the United States has not returned to the moon since 1972. Many Americans thought the next step, to be taken in the relatively near future, would be a journey to Mars. However, this has not come to pass. More recent developments highlight the uncertain future of U.S. space exploration. Congress has extended NASA’s operations on the ISS until 2024. What will happen to it after that remains to be seen.

China is determined to do things differently, and is moving forward as a result. By the time NASA’s involvement with the ISS comes to an end, China’s planned space station module, Tianhe-1, will likely be operational and will offer an alternative opportunity for human spaceflight. Chinese taikonauts may well be the next humans to set foot on the Moon. The American public and politicians may not care about such developments, but they should. Space travel has been – and always will be – a sign of a country’s strategic vision and capabilities, both of which are strongly related to global influence. The latter is a commodity that the United States is losing at a rapid rate.

. . .

Joan Johnson-Freese is a Professor of National Security Affairs a the Naval War College in Newport, RI and holds the Charles F. Bolden, Jr. Chair of Science, Space and Technology there. She is the author of multiple books on space issues, including Space Warfare in the 21stCentury: Arming the Heavens.