Title: The Fourth Coast: America’s New Challenges in the Arctic

On November 30th, 2018, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake rumbled through southern Alaska. The powerful quake caused extensive damage throughout the region as roads buckled, overpasses collapsed, and water and gas lines ruptured. For a while, Anchorage and its roughly 300,000 residents were cut off from the outside world as thoroughfares into the city became impassible.

Within minutes of the event, national news outlets were covering the disaster and Alaska briefly entered many Americans’ consciousness. However, by the end of the day, with no human deaths to report, the story itself died, and Alaska faded from public discourse. Such is the plight of the people who inhabit “The Last Frontier.” Most Americans and their leaders pay little attention to what happens in Alaska – Washington, D.C. is closer to Paris than it is to Anchorage. However, extraordinary changes are happening in Alaska, particularly in the part of the state that lies above the Arctic Circle. Arctic sea ice is melting at the fastest rate in over 1,500 years, glaciers have receded to record lows, and the ground is thawing beneath thousands of homes and billions of dollars of infrastructure. The unprecedented environmental transformations occurring in the state will have far reaching consequences for all Americans.

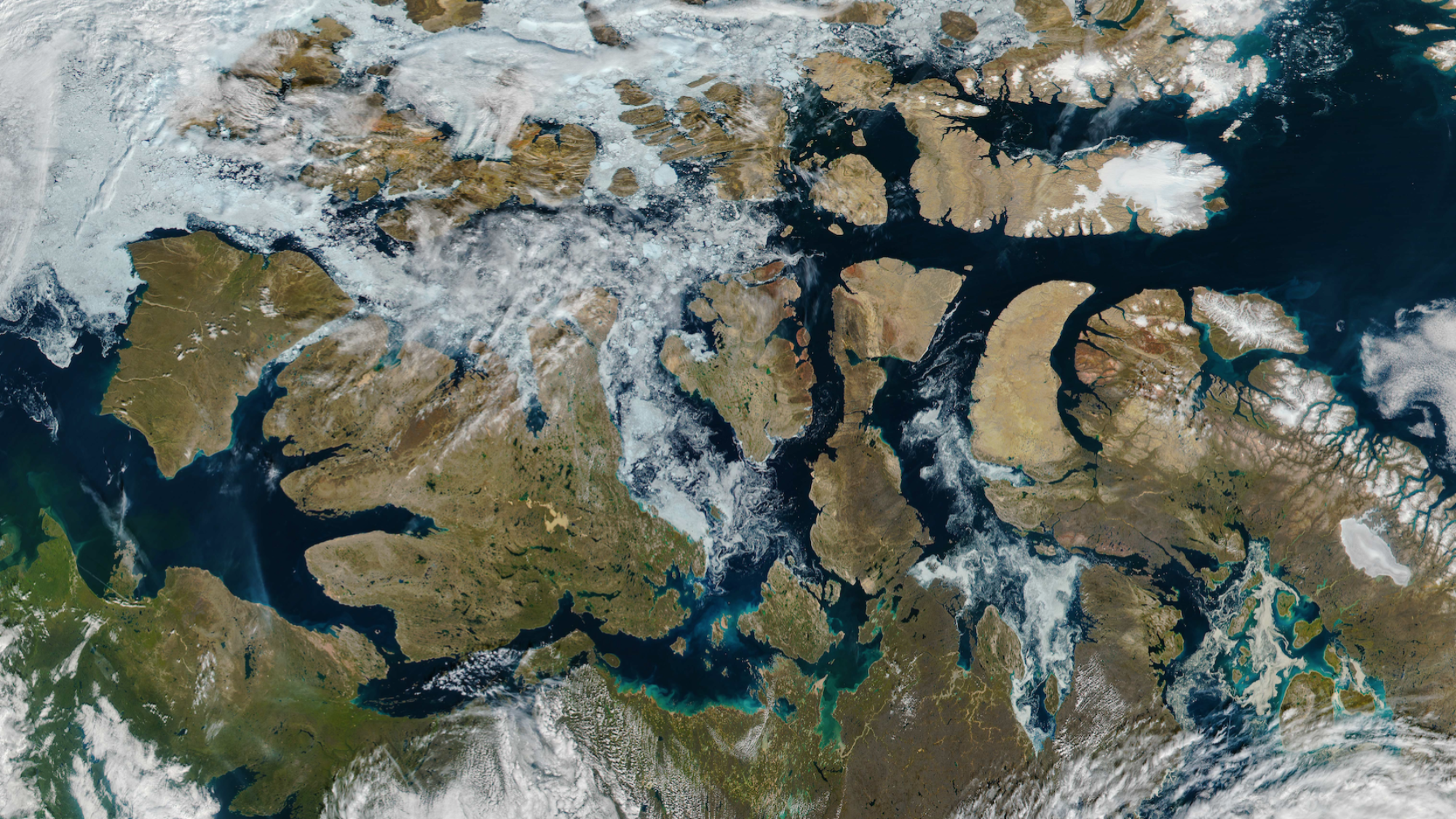

A little over a decade ago, a group of scientists noticed dramatic changes in the sea ice that covers the Arctic Ocean for most of the year. The ice melted more each summer as temperatures in the region increased twice as quickly as the rest of the planet. Within a few years, the sea ice that had covered the region for thousands of years vanished and the once frozen ocean was largely open during the summer months. The melting ice moved hundreds of miles off the Alaskan shore, and the fabled Northwest Passage – the sea route connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific via the Arctic Ocean – opened up through the Canadian Archipelago. Almost immediately, this environmental shift created enormous problems.

Without the buffer of coastal ice, long-inhabited coastal towns and villages were battered by huge storms. As the coastline was inundated with high waves and storm surges, rapidly increasing temperatures thawed the soil and subsequent erosion washed houses and critical infrastructure into the surf. Many communities began to plan for a forced relocation to higher ground. As most Americans focused on the impacts of hurricanes and sea level rise in places like Florida and the Gulf Coast, they paid scant attention to the unfolding disasters in Alaska.

When the media covers transformations in the Alaskan Arctic, it is usually to herald the opportunities emerging as the Last Frontier begins to open. Oil and gas interests have looked for new reserves in the Arctic Ocean’s shallow waters and international shipping companies are plotting new routes through the open waters. Occupying nearly half of the land above the Arctic Circle, Russia in particular has begun to exploit its dominant position. As Russian natural gas poured out of the Arctic, the Russian government began to build up its Arctic infrastructure in a manner not seen since the height of the Soviet Union. When Western sanctions against Russian energy companies threatened the country’s energy renaissance, the Russians turned to China, an unlikely new ally and historical adversary, to help them continue to develop their oil and gas industry. This new coalition has pushed two powerful U.S. competitors closer together at a time of geopolitical realignment. This marriage of convenience between the two dominant Asian countries could have far reaching implications for U.S. security and influence in the region. A strengthened alliance between two powerful Arctic states could affect everything from monopolistic Russian energy supplies to NATO countries in Europe to Chinese dominance in Southeast Asia.

China, with its thirst for cheap energy, was eager to exploit the rift that opened between the West and Russia. The energy agreement with Russia not only positioned China to take advantage of Russian resources, it also helped the Chinese government access the newly cleared Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic coast. This new route is a centerpiece of China’s One Belt One Road policy, as it opened an alternative route to Europe for China that bypasses the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean, where the U.S. Navy retains supremacy. The rerouting of ships through the Arctic could alter the way commodities are transported and disrupt global shipping routes that the U.S. has maintained and largely secured since the end of World War II.

Closer to home, the opening of the Arctic has exposed thousands of miles of Alaskan coastline to a growing wave of drugs and other contraband. The influx of narcotics has devastated Alaskan communities where law enforcement is already stretched thin. Rates of drug addiction and suicide have skyrocketed in the past few years, especially among younger residents. The absence of a sustained federal law enforcement presence along the Alaskan coast has also created human trafficking problems and questions of national security as people can enter the country largely unchecked. The northern border of the U.S. along its new fourth coastline in the Arctic is now far less secure than the southern border from a monitoring and law enforcement standpoint. As more commercial ship traffic moves through the Arctic, the opportunity to move illicit cargo and people into the U.S. through unsecured coastal communities in Alaska will undoubtedly increase.

The U.S. response to these rapidly changing conditions in the Arctic has been haphazard at best over the last few years. With only two functional icebreaker ships, one of which is committed to the Antarctic for most of the year, the U.S. has limited capabilities to project force, deal with emergencies, or respond to unfolding events in a new, escalating geopolitical theater. Looking forward, the U.S. must pay more attention not just to America’s sector of the Arctic, but to the whole region, as Russia and China continue to advance into this new space and other countries look to take advantage of emerging opportunities.

The U.S. needs a three-tiered strategy for securing the Arctic. First, it must provide resources at the local level to support communities dealing with threats ranging from coastal erosion to drug addiction. Congress must fund federal programs to increase food and human security throughout the region. Second, the U.S. must better integrate the Arctic into national strategies concerning energy development, rare earth resources, and the food supply. Finally, the U.S. must create a unified national strategy that includes defense, intelligence gathering, border security, and disaster response to deal with the emerging international challenges in the Arctic. This will require not just resource investment, but also sustained commitments from the legislative and executive branches to fund, organize, and manage U.S. Arctic policy.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, America’s Manifest Destiny added two new coastlines to the Eastern Seaboard that made the country a global superpower. In the 21st century, America will have a fourth coastline to not only exploit, but to defend. If it does not pay more attention to this region, the next big shakeup in Alaska may have nothing to do with an earthquake.

. . .

Jeremy T. Mathis is an adjunct professor of environmental policy in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and is a board director at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. He directed NOAA’s Arctic Research Program from 2015 to 2017 and served on Senator Lisa Murkowski’s (R-Alaska) staff in 2018. Professor Mathis has made over 20 trips into the Arctic and authored over 80 peer-reviewed publications.