Title: Part I: (Un)Accountability for Torture

The following is the first of a two-part series.

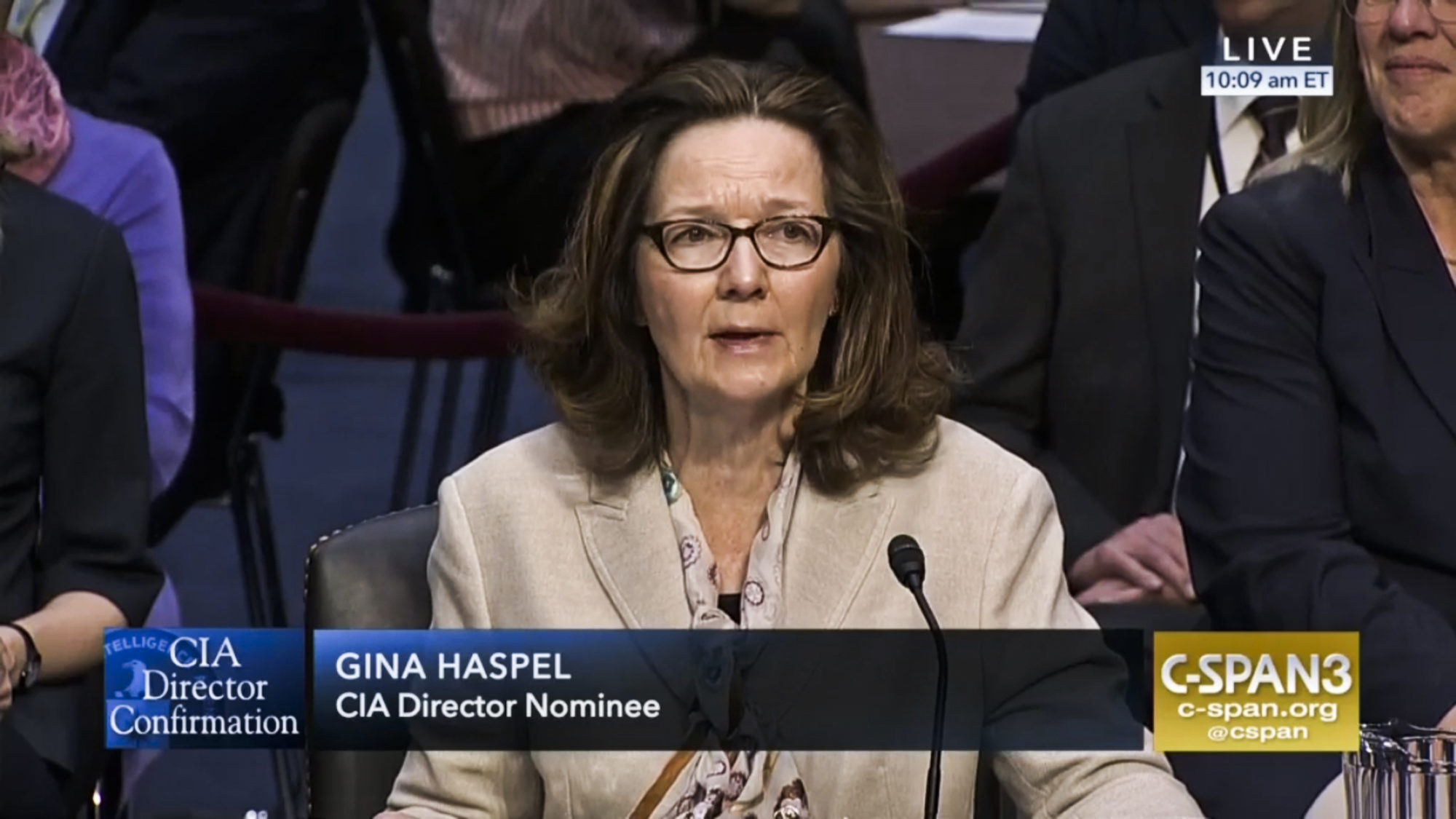

With the nomination and eventual appointment of Gina Haspel to the directorship of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), debates around the legality and the morality of the torture program undertaken during the early years of the War on Terror resurfaced. Some editorials asserted that condoning torture was now a roadmap for promotion at the CIA. Others, including former senior leaders of the CIA, argued that none could lead the Agency better than Haspel and claimed she was a person of integrity. Yet, amid the debates about her leadership of the Agency loomed two larger questions: 1) who is most responsible for the torture program, and 2) what does accountability mean? In the balancing act between the demands of justice and the imperatives of national security, how can we best ensure that the right people are held accountable for the U.S. torture program? Forceful repudiations of the program did occur through both internal agency proceedings as well as in the form of checks and balances across the federal government, but the public view of torture has changed in the almost two decades since 9/11. This shift is significant because U.S. popular opinion against the torture program a decade ago significantly contributed to pushback against it, pushback that manifested in the accountability measures detailed below. In the absence of public opposition, accountability measures will be more elusive.

To answer these two questions—who is responsible and what accountability would look like—we need to review these dark moments in U.S. history with an eye toward identifying those most responsible, assessing what measures were taken to ensure accountability, and examining why public mobilization around torture constitutes a national security issue.

What Happened and Whose Fault Was It?

Following the 9/11 attacks, the George W. Bush administration authorized the CIA and the Department of Defense (DoD) to use a range of extraordinary tactics—many adapted from Chinese methods used against U.S. soldiers during the Korean War—to extract information from captured detainees. A 2002 memo authored by Alberto Gonzales, then White House Counsel, concluded that interrogation methods of the past were no longer adequate for the demands of the War on Terror. According to the 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report, the CIA’s new authorities covering rendition, detention, and interrogation—as well as the perceived need for immediate actionable intelligence—resulted in around one hundred people being subjected to coercive treatment, including three who were waterboarded.

Former senior Bush administration officials argued that the DoD’s program was the work of a “few bad apples;” indeed, if responsibility is measured by who was prosecuted or removed from their jobs, the answer would seem to be the interrogators themselves. Yet, in reality, the greatest responsibility for the CIA and DoD’s torture programs lies with lawyers and senior Bush administration officials who repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to challenge the normative and legal constraints imposed by the Geneva Conventions and the United Nations Convention Against Torture. The legal authors of the program—individuals like John Yoo at the DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) and David Addington in the Vice President’s office, for instance—argued that neither Congress, the courts, nor the American public could unduly limit the powers of the unitary executive in general, especially during wartime.

What Accountability Steps Were Taken?

After revelation of the programs, accountability measures were taken both within and across agencies, yet the missing piece has been the role of the public in repudiating this program. Particularly in this realm of human rights and war, without this kind of public accountability, illegal behavior is not only left unchecked. The torture committed during the early years of the War on Terror seemed to validate the core narrative that al-Qaeda has long held that the United States was an immoral, hypocritical state with wanton consideration for Muslim life. In this way, accountability is not just a moral imperative, a measure to guarantee compliance with the law, or a means of ensuring the proper allocation of resources. It is a national security priority.

Political scientists Ruth Grant and Robert Keohane (2005) lay out the following foundation of accountability:

Accountability, as we use the term, implies that some actors have the right to hold other actors to a set of standards, to judge whether they have fulfilled their responsibilities in light of these standards, and to impose sanctions if they determine that these responsibilities have not been met. Accountability presupposes a relationship between power-wielders and those holding them accountable where there is a general recognition of the legitimacy of (1) the operative standards for accountability and (2) the authority of the parties to the relationship (one to exercise particular powers and the other to hold them to account).

Keohane further develops eight types of accountability that grant individuals and groups the power to sanction power-wielders: hierarchical, supervisory, electoral, fiscal, legal, market, participatory, and public reputational accountability. In the post-9/11 era, a number of these mechanisms were successfully instituted, namely in the hierarchical, supervisory, electoral, and legal realms.

With regard to internal agency hierarchical accountability, the DoD convicted eleven soldiers in military trials for the abuses at Abu Ghraib and issued a new Army Field Manual that explicitly prohibits the cruel treatment of detainees. The CIA conducted six accountability proceedings from 2003 to 2012, which assessed the actions of thirty individuals involved with the program in some way. According to the Senate Intelligence Committee report, of these thirty people, sixteen were deemed accountable, and one contractor was fired. Lastly, in 2004 the Department of Justice (DoJ) withdrew the Bybee torture memos originally released in 2002. In 2009, a report from its Office of Professional Responsibility concluded that the torture memos “fell short of the standards of thoroughness, objectivity, and candor that apply to DoJ lawyers.” The report assigned specific responsibility to the individuals who originally produced this legal advice: Yoo, Jay Bybee, Patrick Philbin, Steven Bradbury, among other department officials. However, no further material action was taken to punish these men beyond their listing in the OPR report.

In addition to measures taken inside the agencies most responsible, there were wide checks across the federal government. While the Supreme Court affirmed in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006) that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions—which includes a humane treatment requirement—applied to the conflict between the United States and al-Qaeda, concrete public reckoning also came from Congress, in the form of both oversight and statutory guidance. With the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 and the Military Commissions Act of 2006, Congress strongly repudiated coercive practices in interrogation. These legislative actions were driven in large part by the leadership of torture-survivor Senator John McCain who specifically sought to codify in law the normative prohibitions against torture.

Congress also pursued accountability through its oversight function. The Senate Armed Services Committee examined DoD actions regarding detention in a 2008 report, and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence issued a 6,000-page review of CIA detention practices in December 2014 (though only the 538-page executive summary has been declassified). Lastly, Congress effectively banned torture by passing an amendment to the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act that limited interrogation techniques to those contained in Army Field Manual 2-22.3.

These wide measures constitute a serious attempt to assign blame. Many of the measures investigated past abuses, punished some of those responsible, and put in place barriers to prevent abuse from happening again. In addition to these measures, citizens also played a vital role in the initial processes of policy and accountability, particularly through public advocacy. In fact, Georgetown Law Professor David Cole argues that critical decisions such as Hamdan v. Rumsfeld only became possible after small, but vocal, advocacy groups amassed political momentum behind granting legal protections to detainees. In the buildup to the 2008 election, candidate Barack Obama decried the use of enhanced interrogation techniques and advocated for the closure of the Guantánamo Bay detention facility, stances that brought these issues to the forefront of national conversations. Obama then issued EOs 13491 and 13492 immediately following his inauguration, reversing Bush administration policies on detention and interrogation and reaffirming his commitment to close Guantánamo. Yet, after those early moments, public attention to, and interest in, accountability eroded, and the American public has not shown sustained interest in holding senior leadership accountable for their decisions. While there was a public outcry following the scandals at Guantánamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, the public memory is fleeting and the American people have moved on.

. . .

Professor Elizabeth Grimm Arsenault is an Associate Professor of Teaching in the Security Studies Program in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown. She was presented with the Dorothy Brown Award in 2012 by the Georgetown University Student Association on behalf of the undergraduate student body and also received the School of Foreign Service Faculty of the Year Award in 2012. She is the author of How the Gloves Came Off: Lawyers, Policy Makers, and Norms in the Debate on Torture.