Title: The Political Economy of Venezuela and PDVSA

Venezuela is in the throes of an unprecedented economic collapse. Oil, Venezuela’s lifeblood, is being mismanaged by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), the country’s state-owned oil company. Faced with dwindling revenue from PDVSA, the government has relied heavily on credit from its central bank to finance government expenditures. Meanwhile, the Banco Central de Venezuela has turned on the printing presses, creating a crisis of hyperinflation.

In total, there have only ever been fifty-eight hyperinflations worldwide, and Venezuela is the only country in the world currently experiencing hyperinflation. On January 1, 2020, the annual inflation rate was 6,869 percent per year. By virtue of a wider comparison, Venezuela’s hyperinflation can be described as relatively modest in magnitude, but unusually prolonged. As of January 2020, it has lasted thirty-eight months, making it the third longest hyperinflation in history.

Hyperinflation is when the rate of inflation exceeds 50 percent per month and persists for at least thirty consecutive days. Historically, hyperinflations have only occurred when the supply of money has been governed by discretionary, paper-money standards. No hyperinflation has been recorded in any economy that relies on commodity-based money or paper money that is convertible into a commodity.

Closely linked to Venezuela’s hyperinflation is the mismanagement of PDVSA, a state-owned enterprise (SOE), which dominates the economy and accounts for almost 95 percent of Venezuela’s foreign exchange earnings. Even by SOE standards, PDVSA is grossly mismanaged, as evidenced by its production and reserve figures.

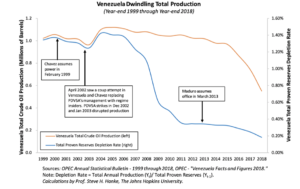

Under the direction of Luis Giusti in the 1994-1998 period, PDVSA’s production soared. This trend changed in 1999, when Hugo Chavez became Venezuela’s president and introduced Chavismo as the guiding economic doctrine. Venezuela’s oil output began to stagnate, a situation which worsened further after the coup attempt of April 2002. Chavez responded by purging PDVSA of its professionals en masse, replacing them with “reliable” hands—those loyal to Chavez’s socialist regime.

After the 2002-2003 output plunge, Venezuela’s production temporarily recovered. However, with the death of Chavez and Nicolas Maduro’s assumption of the presidency in March 2013, another output plunge began. This trend has left Venezuela’s output drastically lower than when Chavez took power in 1999. PDVSA’s physical capital has been consumed at an unsustainably rapid rate, with capital expenditures far below the value of equipment that is being consumed each year by depreciation and amortization.

On top of PDVSA’s reduced capital stock and its deteriorating quality, there has also been a drop in the stock and quality of its human capital. For example, in 2017, President Nicolas Maduro named a National Guard general with no industry experience to lead PDVSA. The combination of plunging physical and human capital has left the giant SOE in very bad shape. Equipment breakdowns and increased accident rates have contributed further to long downtimes and output declines.

It is important to note that PDVSA’s decreased output is not due to dwindling oil reserves, but rather is caused by changes in the rate at which its reserves are being depleted. The depletion rate provides the key to understanding the economics of an oil company and the value of its reserves. As the chart above shows, Venezuela’s depletion rate has been falling rapidly since 2007. At present, it sits at 0.182 percent per year, indicating that it would take 380.4 years for PDVSA’s reserves to be halfway depleted.

This has noteworthy economic implications. Because of positive time preference and discounting, the value of a barrel of oil produced today is higher than the value of a barrel of oil produced in the future, provided the price of oil remains the same. Given the incredibly low depletion rate, Venezuela’s reserves—which are the world’s largest, at 9.26 billion barrels—are essentially worthless because they are left in the ground too long.

To put Venezuela’s depletion rate into perspective, consider Exxon, one of the world’s largest oil companies. At the end of 2018, Exxon’s depletion rate was 6.74 percent per year—a rate comparable to that realized by most major oil companies. That rate implies that it would take 9.9 years for Exxon’s oil reserves to be halfway depleted. That is 370.5 years earlier than when PDVSA would deplete half of its reserves. Indeed, if we discount at 10 percent, the median value of Exxon’s reserves is worth 39% of their wellhead value (the value that the producer would receive if the oil was sold at the wellhead and not distributed further downstream)—not zero, as is the case for PDVSA.

The country with the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuela is plagued by a mismanaged, state-owned oil company in a death spiral—PDVSA. This mismanagement has thrown the country into a hyperinflationary death spiral of its own, suggesting that, in the memorable words of former President George W. Bush, “this sucker could go down.”

. . .

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. He served as an adviser to Venezuela’s President Rafael Caldera from 1995 to 1996 and is a premier authority on hyperinflation.