Title: Peace in Northern Ireland: A Model for Ending Wars?

When Good Friday fell on April 10 this year, it was exactly twenty-two years to the day after Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement was signed. That watershed deal of 1998 cemented peace in the Province—a peace that has lasted almost as long as the conflict it brought to an end.

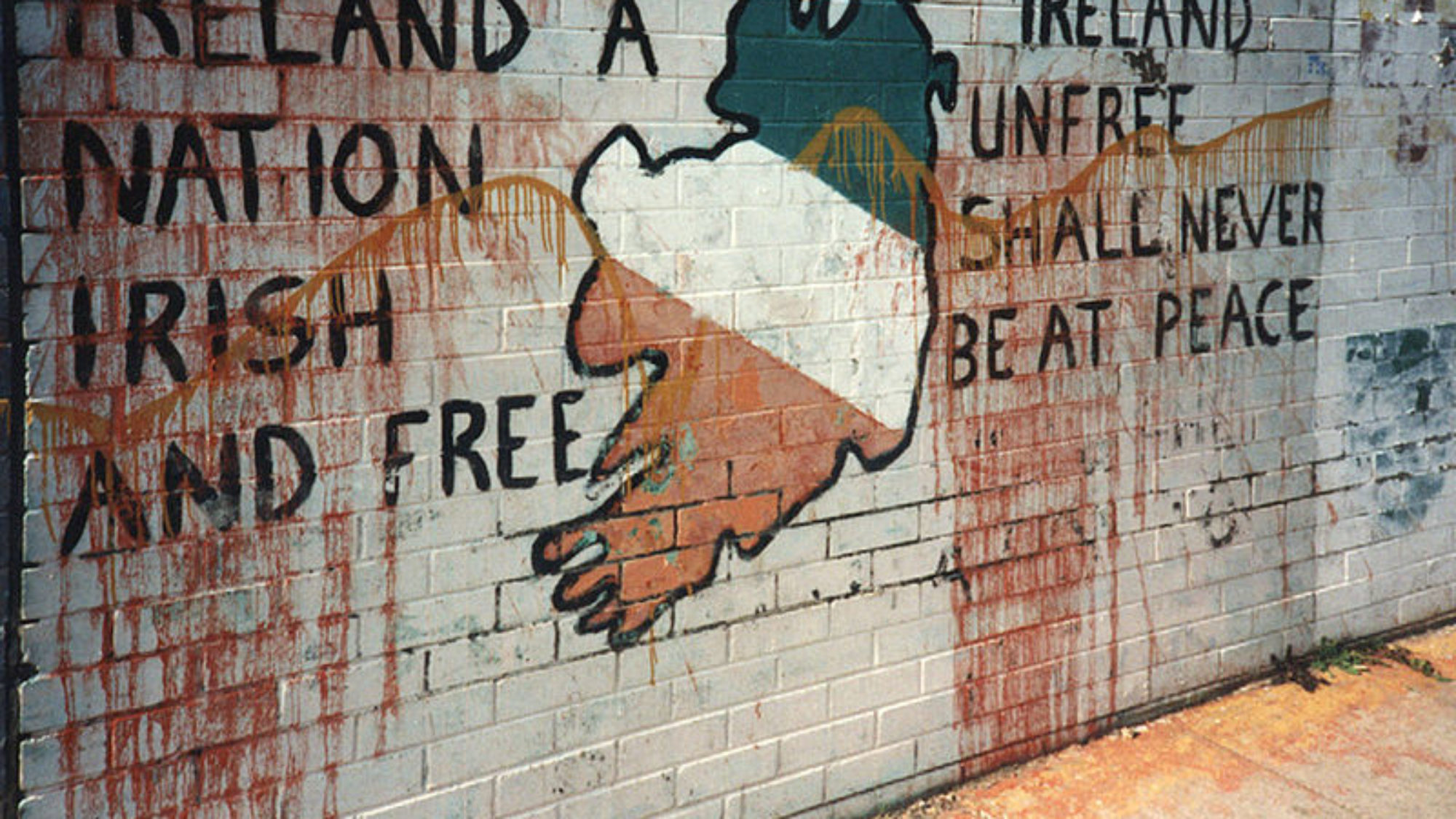

The accord was hugely significant, not least because it was so unexpected. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, television news in the United Kingdom and Ireland would feature reports of bombings or shootings with grim regularity. Politicians and community leaders exhausted the lexicon of condemnatory terms. More than 3,600 people were killed in the 30 years leading up to Good Friday in 1998, half of them civilians, with thousands more suffering life-changing physical or mental scars. For most of that time, the conflict seemed intractable.

The path to the Good Friday Agreement was complex; even after the republican and loyalist ceasefires of 1994 there was a brief return to violence in 1996. Nevertheless, it bears several important lessons, some of which can be applied to other conflicts today. The following are four of those lessons, with contemporary applications of each.

First, it was clear by the 1990s that none of the protagonists would capitulate or be fully defeated; as a result, a compromise was the only way to end the violence. To make such an outcome sustainable in the long run, it was not just the elites who needed to be satisfied, but also the communities they represented. The identity of rival groups, including their sense of dignity and their treasured symbols, had to be respected; historic grievances had to be acknowledged; and systematic imbalances in power and representation had to be addressed. Everybody had to be given an incentive to support the deal. The agreement had to be inclusive and offer far more than just an end to violence.

This lesson applies today in Venezuela: a sustainable settlement for the standoff which consumes Caracas requires a peace package that is attractive to the broad mass of the Venezuelan public. It needs to be inclusive and bring in communities otherwise inclined to support the current Maduro regime. This is the most promising way to sideline Maduro himself, as well as his inner circle, so that the internationally-recognized leader, Juan Guaido, can take charge without bloodshed.

Second, political power in Northern Ireland had to be detached from the capacity to commit acts of violence. This was crucial; until the peace talks, paramilitary groups had sought to use terror to achieve political goals, which was unacceptable, especially to democratically elected politicians who abhorred violence. The solution was to invite established paramilitaries into talks on the conditions that they renounced violence and received the votes of a sufficient number of electors in a special election. These so-called “Mitchell Principles” gave former terrorists access to a truly democratic mandate, and endowed them with legitimacy at the negotiating table, while also reassuring those who had always been committed to exclusively peaceful politics.

This lesson applies in today’s Afghanistan, where a conditional and partial withdrawal is transforming a nineteen-year US engagement. Talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government could benefit from something similar to the Mitchell Principles. Just as Sinn Fein transformed itself from a militant group into a democratic and legitimate political party, the Taliban could too, and should be encouraged to do so. It would require the Taliban to offer certain assurances on human rights—and stand firm against hardliners in their own ranks who refuse to make the transition. Experience from the Northern Ireland model suggests that former Taliban prisoners released through an amnesty will be the most persuasive in arguing for moderation.

Third, some topics were too complex to resolve alongside the others, and could only be settled after the main Good Friday Agreement was enacted. The two most sensitive issues were reforming Northern Ireland’s police force and decommissioning paramilitary weapons; it took several more years of dedicated political commitment until both issues were settled. In 1998, though, a balance needed to be struck—if too much had been put off until later, the overall Good Friday Agreement would be weaker.

If the international community is to reconcile with North Korea this year, a similar sequencing of issues would be necessary. The main deal may involve verified nuclear safety guarantees in return for commitments on North Korea’s territorial integrity. Details about how Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal would be decommissioned, and how the country could benefit from integration into the world economy, would follow later.

Fourth, although by the 1990s there was strong public will for a peace deal, many politicians and activists believed they needed to take an inflexible position—several lived in a “bubble” among hardliners, while some ambitious figures sought to define themselves in opposition to any sort of compromise. Negotiators resolved this problem by putting the final deal to a vote, holding referendums in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The resulting public endorsement was overwhelming and integral to the survival of the Good Friday Agreement.

Today, there are several places in which a future deal negotiated by governments may need to be cemented by a carefully-constructed referendum. This could apply to Kashmir, Israel-Palestine, and Cyprus—all places where rival communities take polarized positions, and where some hostility is likely to remain even if an overarching peace deal is agreed upon.

The twenty-two years since the Good Friday Agreement was signed have not been easy. It took the largest unionist party more than eight years to accept sharing power with Sinn Fein, not least because the IRA, for its part, was slow to decommission its guns. Even non-aligned groups who refused to take sides between the main rival communities were disappointed by the slow progress on some aspects of the agreement.

But, by the most basic measure, the Good Friday Agreement was and remains a great success: violence has ended, viable political structures are in place, and they are functioning reasonably well.

Can the Good Friday Agreement model apply elsewhere? Certainly. Indeed, in 2000, the Good Friday Agreement was used as a model for a political settlement in northern Kosovo. Remnants of those talks, such as the weighted representation of minorities, persist today in Kosovo’s constitution.

There is, however, a danger of transcribing Northern Ireland’s deal as a blueprint. The Good Friday Agreement was developed for a particular time and place, and it derived much of its authority from the talks process which led up to it. The solution cannot be simply replicated elsewhere, nor can it just be adapted.

April 10, 1998 was a remarkable day—one which showed that even the most intractable conflicts can find a path to peace. But we will only find that path for the conflicts of today if we understand the Good Friday Agreement was much more than a peace deal. It was the product of sustained political effort over several years, and its success ultimately derived from a deep and iterative engagement with the political environment.

The single most important lesson the Good Friday Agreement offers us for today’s conflicts is this: we must study in depth those conflicts themselves, so that we understand them, if we are to end them for good.

. . .

Iain King CBE is the UK Visiting Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS, and spent the years 1993-2000 working on the Northern Ireland peace process.