Title: US-Iranian Relations Remain on Track for Escalation

Iran is currently facing an incredibly unlucky alignment of pressure sources that are interrelated and will force the regime to engage in risky or experimental behavior, most likely in 2020. The COVID-19 epidemic simply exacerbates the combined challenges of a regime squeezed by an international sanctions network and a restive population reaching a breaking point with economic hardship. A continued acceptance of the status quo is untenable; thus, the regime will likely begin to undertake various initiatives in the coming months, more likely military than diplomatic in nature, that could force the United States to ease the isolation of the country.

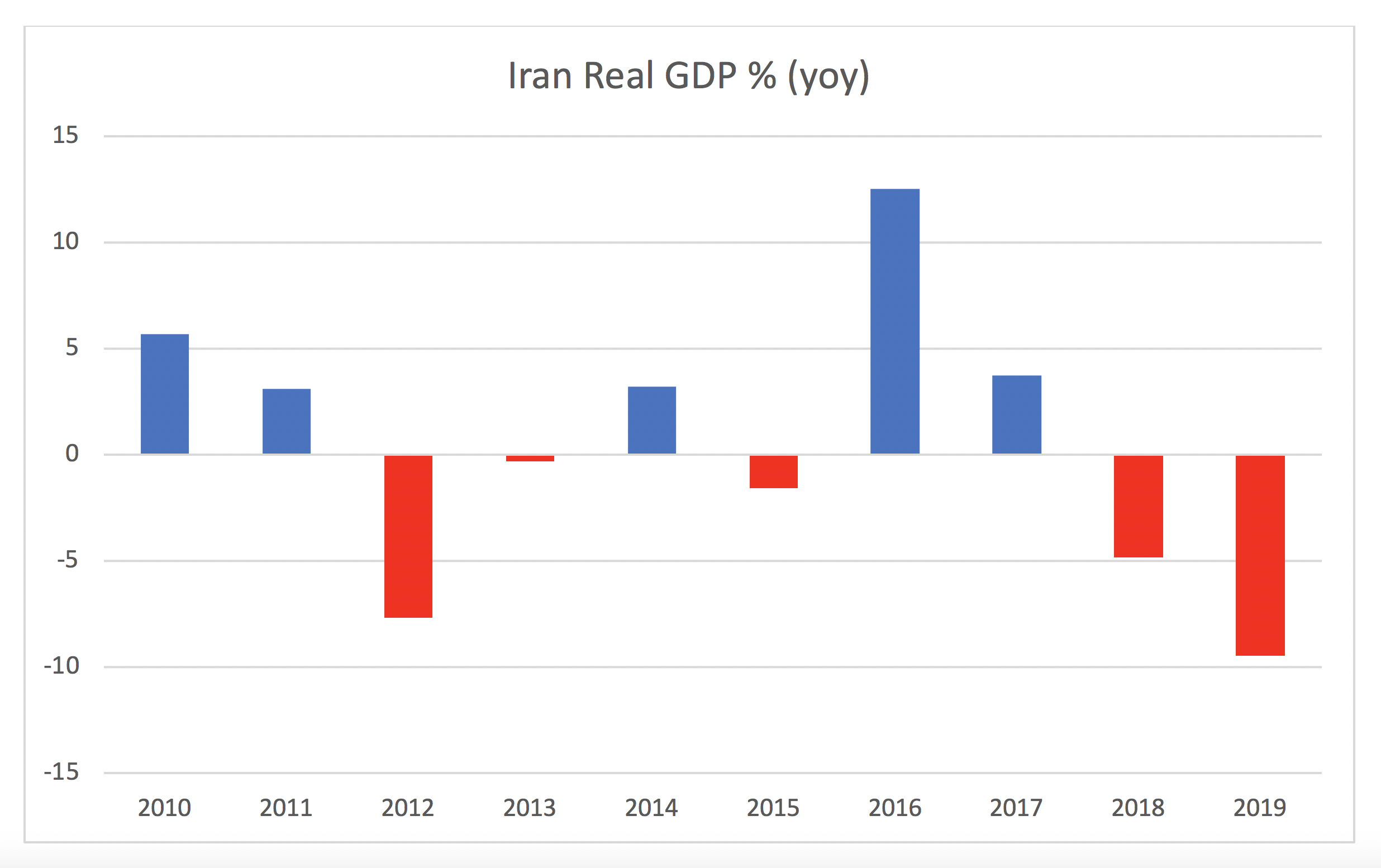

While regime continuity is not in doubt, Iran is undergoing its worst period of turmoil since the 1980s. The sudden closing of external trade, currency depreciation, and concomitant inflation has imposed severe economic burdens on the population just a few years after the previous episode of sanctions-induced recession in 2012. As Fig. 1 shows, the IMF estimates that the economy may have shrunk by nearly ten percent in 2019 while inflation has risen above thirty-five percent.

Fig. 1: Iranian Real GDP Growth 2010-2019 (%)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook October 2019

The result has been popular unrest at increasing frequency and in larger numbers. While the exact figure is hard to confirm, the Iranian government killed several hundred protestors in late 2019 in order to restore calm. More noteworthy than the harsh government response is the widespread nature of the protests, which extended into second-tier cities and provincial towns in the hinterland. It appears that a wider swath of society participated, including the working classes and groups assumed to be loyal to the regime. The latter was not demanding regime change but rather clamoring for a massive change in their economic well-being.

It is in this context that the outbreak of COVID-19 is particularly damning. The regime has suffered irreparable loss of credibility in the wake of the Soleimani killing and the accidental downing of a passenger plane in early January. It showcased a combination of incompetence, lack of transparency, and blatant disregard for the lives of citizens. It is not a coincidence that Iran is among the countries with the highest number of deaths from COVID-19, given that the pandemic is a public health crisis where effective policy tools rely on public trust and communication with governmental authorities. It is particularly troubling that the epidemic was centered in the holy city of Qom and that the virus had circulated among leading government officials, as these factors potentially exposed the regime’s core constituencies to government missteps. The record low turnout in February’s parliamentary elections was a warning sign that mass discontent had spread far beyond the usual demographics.

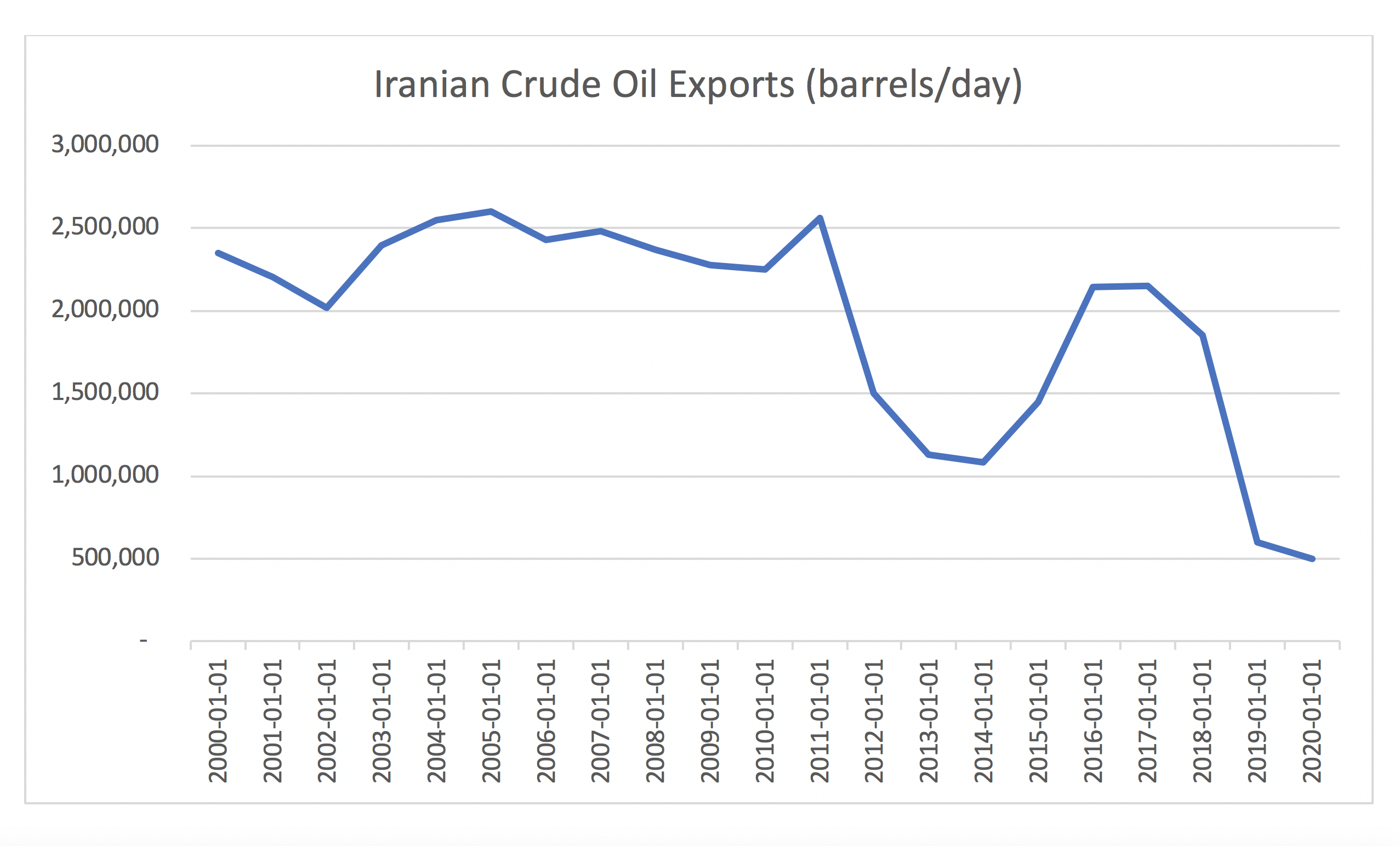

Under such duress, many semi-authoritarian regimes would consider popular domestic measures, such as enhanced public spending or liberalizing repressive policies. Iran can do neither. As Fig. 2 indicates, its fiscal options are limited given the collapse in oil exports related to US-led sanctions and ultra-low oil prices. An inability to borrow debt in global markets or tap credit lines also prevents any major fiscal stimulus.

Fig. 2: Iranian Crude Oil Exports 2000-2020

Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data)

Any domestic liberalization would run afoul of the internal power shift, as hardliners are gradually retaking government institutions which they have not controlled in recent years. Having engineered their recent parliamentary election victory, they now have their sights on the presidency and executive bodies, for which they will need to wait until the June 2021 elections. In the meantime, they would rather deny current President Rouhani any victories.

So, what can be done? The most viable option would be to launch an external initiative to hopefully break the isolation. Logically, this would require either bringing the United States back to the negotiating table or coalescing all other major powers behind an alternative. The latter is outright fanciful, so focus should be on what measures Iran could consider to lure the United States back. This would broadly fall into either a diplomatic or military initiative. As with any domestic initiative, any diplomatic success would be a credit to the Rouhani government and would thus not receive the necessary backing from other regime power centers.

That only leaves the option of a hawkish maneuver. This has been Iran’s strategy since President Trump withdrew from the JCPOA; escalatory provocations with the United States led to Soleimani’s assassination. Despite that failure, the strategic logic still holds that Iran needs to demonstrate to the United States that the steady ratcheting of US pressure could be counterproductive. Hence, we should expect continued provocations on the nuclear front, with the gradual restoration and expansion of the nuclear program with strong—yet deniable—undertones of weaponization. The other escalatory track would be military adventurism in the near abroad, though Iran would be more hesitant to confront US assets directly as it had in Iraq in December 2019.

Nonetheless, as time passes, hesitation will give way to desperation as the current track is simply unsustainable for the regime. The country will not find a new, lower base level of economic stability, as the sanctions logic means an ever-increasing squeeze on the country’s economy. In February, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) decided to re-impose sanctions on Iran after its failure to legislate counter-terrorist financing laws. In and of itself, this is only another marginal step in reducing international financial links with Iran. Absent a major change in US-Iranian relations, however, the Iranian economy and resulting public rage will continue to worsen. Iranian incentives to upset the status quo will therefore grow, and the US election cycle—with an incumbent running on putting an end to “endless wars“— offers further encouragement for Tehran to escalate sooner rather than later. [1]

. . .

Elliot Hentov is the Head of Policy Research with the Global Macro Policy Research team at State Street Global Advisors, where he serves as the company’s main geopolitical strategist. He is also a member of the Advisory Board of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum in London and a Non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC.

[1] Since the writing of this article, U.S.-Iran tensions have continued to escalate.