Title: Defining Problems in the Face of Urgency: Climate Change and the Arctic

An apocryphal story credits Einstein with saying that, if given an hour to solve a problem, he would spend fifty-five minutes defining the problem. Regardless of the attribution, the sentiment is especially valuable to our thinking about climate change. It is wise, indeed, to devote sufficient time to understanding a problem before attempting a solution. There is great urgency, however, to the problem of climate change, especially in the Arctic, a region warming at more than twice the global average rate. Asking the right questions in the Arctic is both urgent and important for correctly defining climate problems globally. It is vital to understand our changing climate in the context of the earth’s history and the history of the Arctic’s Indigenous People, who now bear the brunt of rapid warming. Informed by history, scientists and Indigenous People must assess where the Arctic environment is headed and share their knowledge in words accessible to those who influence and make policy. Moreover, the words of policymakers should help define, for researchers, the most urgent societal needs. The Study of Environmental Arctic Change (SEARCH) approaches environmental Arctic change with a recognition that history, people, and words matter. Paying attention to the Arctic’s past, its inhabitants, and how we talk about its environment is necessary to properly define the problems.

History matters. When dinosaurs roamed the planet (250 – 60 million years ago), the climate was several degrees hotter than at present. In the following fifty million years, the earth gradually cooled and only reached the temperatures we experience about two to three million years ago, not long after the first human ancestors began walking upright. At the same time, ice began to cover portions of the world’s oceans and land. For the past one million years, the long-term cooling trend gave way to regular cycles of glaciation and retreat of glaciers. Thus, the earth’s climate has undergone even greater changes than those so far observed as a result of human-induced warming. It is important to note, however, that those larger changes preceded modern humans.

People matter too. Since first appearing about two hundred to three hundred thousand years ago, modern humans have been influenced by the earth’s climate. However, since the invention of agriculture shortly after the end of the last glacial maximum—about ten thousand years ago—humans have exerted increasing influence on the climate. Land use changes associated with agricultural production may well have started adding additional greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, but the earth’s temperature showed little response until the onset of burning coal in the mid-eighteenth century. The ensuing rapid warming of the global climate, at a pace unprecedented in human history, has been amplified in the Arctic by the reduction in area covered by reflective snow and ice, especially sea ice.

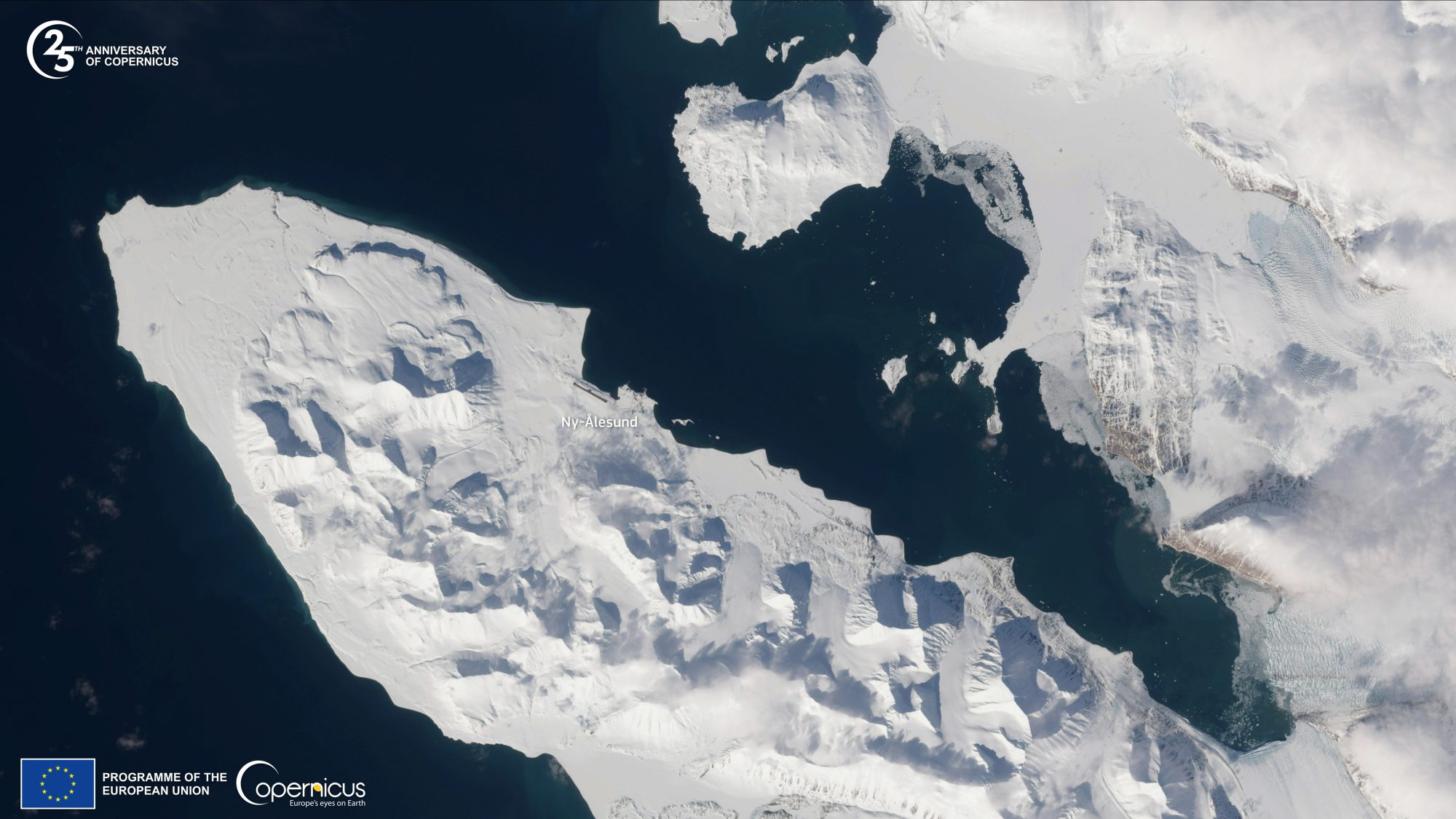

Rapid warming in the Arctic is melting ice on land and in the water and thawing permafrost (frozen soil) with dramatic consequences for people in and beyond the Arctic. The area of the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice has diminished in all months of the year with the greatest losses in the summer months. Consequences in the Arctic include diminished access to traditional food for Indigenous People, damage to infrastructure from increasing waves and coastal erosion, increased marine traffic and offshore development, increased instances of people falling through ice, and challenges to national security. Moreover, diminishing ice cover amplifies global warming by reducing the amount of the sun’s energy reflected back to space, thereby impacting people all over the planet.

Water flowing from melting glaciers and ice sheets is contributing to global sea level rise, and those melt rates have tripled in the past thirty years. The impact on sea level is greater, however, in low latitudes than in the Arctic for two reasons. First, the great mass of ice sheets exerts gravitational pull on the sea, and melted water flows down the resulting slope. Second, some northern lands are rising relative to the sea as they rebound from the weight of ice that covered them during the last glacial maximum. Thus, Alaska’s capital—in the shadow of the melting Juneau Icefield—can expect sea level to fall three feet in this century, while the nation’s capital can expect the Potomac River to rise by one to two feet.

Thawing permafrost is directly impacting life in the Arctic by undermining infrastructure and hastening coastal erosion. In Alaska, thawing permafrost will be a major contributor to infrastructure damage expected to cost as much as $5.5 billion in this century. Permafrost thaw also adds to global impacts by releasing additional greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

Finally, words matter. Even the tenses of words influence how we define problems. In much of the world, climate change seems like something coming in the future, but a loss of Arctic ice and permafrost makes clear that climate change came decades ago. Effective responses to this greatest tragedy of the commons should start with using the proper tense and otherwise being specific in our use of language. The Arctic also gives us a glimpse of the kinds of human impacts we can expect globally including increased human mortalities, displaced communities, and food insecurity. How we talk about the impacts directly influences how we think about solutions, and hyperbole hinders thinking about effective solutions. Alarmism can be as paralyzing as denialism.

At the end of the day, most people care about the quality of life we bequeath to future generations, and our effectiveness in that care depends on clarity. Being clear requires speaking, writing, and listening well across the many actors who must find and implement solutions. Jargon, whether scientific, political, or local, works against clear communication. For example, scientists predicting the future state of the Arctic refer to an ocean with less than one million square kilometers of ice cover as “ice free.” Moreover, they ignore areas with less than fifteen percent ice cover. Thus, when an oil rig was imperiled by sea ice in the Chukchi Sea in summer 2012, it was understandable that a fellow scientist in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) asked me, “How can they be having trouble with ice; I thought the ice was going away?” The implications of saying “ice free” when we mean up to one million square kilometers of ice are substantial for offshore oil development, shipping, and Arctic tourism. We need to say what we mean and mean what we say.

Scientists, policymakers, Indigenous People, and decision-makers need to collaboratively conceive and execute research that will inform critical policy choices. In OSTP, we led efforts across the government to enhance such collaboration. Actionable research requires input from all of those voices using clear, non-technical language. Such a complex collaboration will be difficult to build and sustain, but that is the nature of responding to climate change. For example, our climate models, each comprising over one million lines of computer code, are powerful in predicting where the climate will head under various scenarios, and they are the product of complex collaboration. The reliability and power of these models have increased substantially by expanding the collaboration to include more expert input. Recently, incorporating expert knowledge of how energy interacts with the atmosphere—clouds in particular—led to “dramatic improvements” in a major climate model. Similarly, complex collaborations of experts in science, Indigenous knowledge, business, and public policymaking are essential to realizing sustainable solutions. In terms of informing policy, it is as if we were modeling climate without considering the effect of clouds. Just as in climate science, multilateral collaboration is necessary to generate effective and informed climate policy. We have a long way to go, but there are encouraging examples. SEARCH answers policy-relevant questions about Arctic change in concise briefs written in non-technical language. In Canada, Indigenous communities, scientists, the federal government, and industries transcended language and cultural barriers to establish a large marine protected area in the Arctic. The Indigenous and federal negotiators described the collaboration as challenging but highly rewarding.

Responding to rapid and dangerous environmental change requires not just a whole-of-government approach but also clear communication across many sectors. We do not have time for translation. Indeed, we have already used most—if not all—of the fifty-five minutes available for defining the problem.

. . .

Dr. Brendan P. Kelly is a Professor with the International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks and a Senior Fellow with the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. He has studied sea ice ecosystems in the Arctic and Antarctic for over four decades and worked in science policy in Alaska and Washington, DC including on polar and ocean science issues at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Currently, Dr. Kelly directs the multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional Study of Environmental Arctic Change.

Image Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

Recommended Articles

This article compares U.S. and Chinese approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) exports in Africa and examines how these disparate approaches have produced both downstream benefits and challenges for the region.

On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly unanimously adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, an international treaty designed to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and…

As the Trump administration proposes a sweeping overhaul of the US foreign assistance architecture by dismantling USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and restructuring the State Department, there is an…