Title: Climate Change and the Insurance Industry: Managing Risk in a Risky Time

Often referred to as society’s risk manager, insurance companies have an important role in the web of climate change complexities. Through their investment, underwriting and advisory functions, insurers are directly exposed to a changing climate, which creates threats and opportunities for the sector.

Under the banner of “sustainable insurance,” a growing number of companies have committed themselves to reducing their own carbon footprints, improving their underwriting capabilities, and increasing climate disclosure. However, climate change is still not embedded into day-to-day strategic decisions, and the short-term nature (twelve months) of most insurance contracts still fails to consider the long-term impacts of climate change.

The Impacts of Climate Change on Insurance

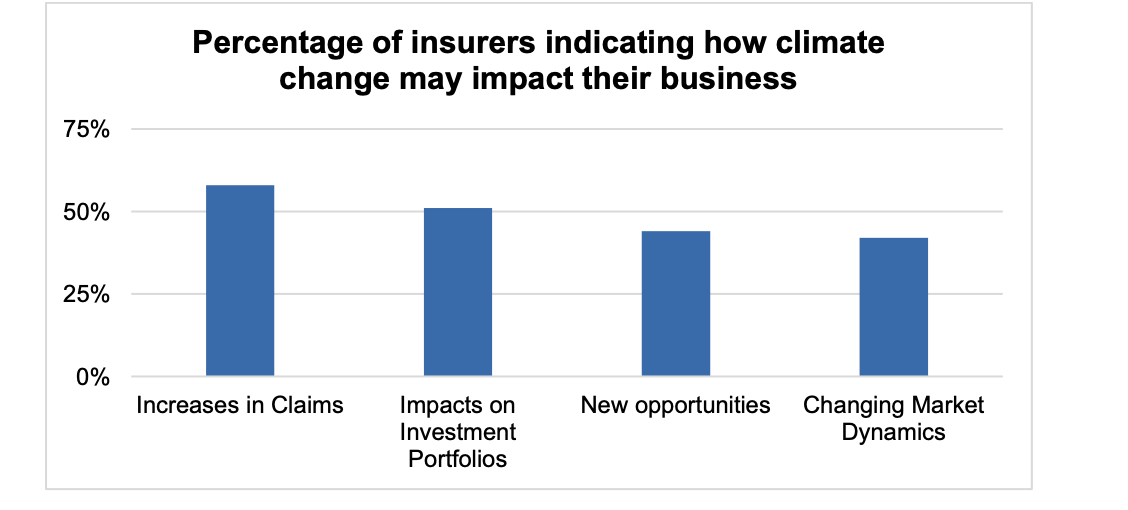

The Sustainable Insurance Forum (SIF), a leadership group of insurance supervisors and regulators, recently conducted a survey of insurers’ climate perceptions and disclosure. The survey also looked at the expected impacts of climate change on insurers. The most commonly cited areas in which insurers said climate change would affect their businesses are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Expected Impacts of Climate Change on Insurers

Source: SIF Survey, 2019 Data

Source: SIF Survey, 2019 Data

The Prudential Regulation Authority of the Bank of England established the now common distinction between physical, transition, and liability risks as a way to describe the channels through which climate change is impacting the sector, its investors, insurance customers, and regulators.

Physical Risks

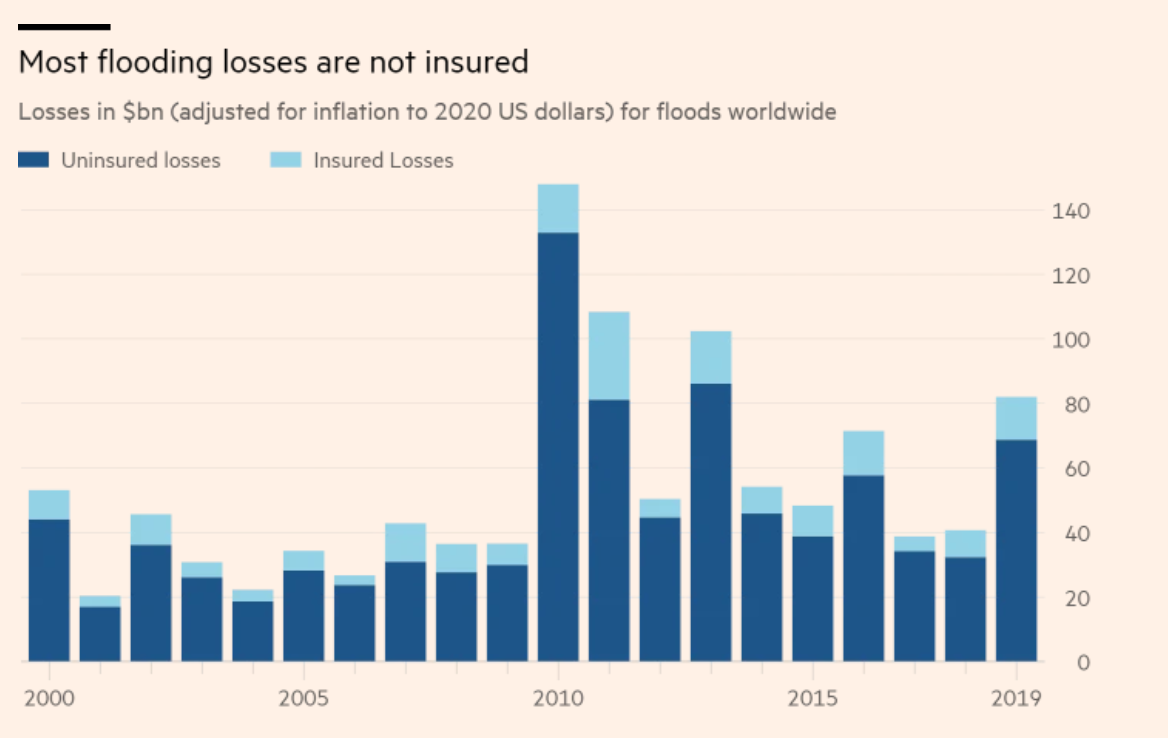

The most obvious link is through so-called physical risks, e.g. the impacts that climate hazards such as floods and storms have on individuals, communities, businesses, and countries. In many regions around the world, these impacts are on the rise, having been driven by climate change as well as growth in exposure (more assets in harm’s way) and vulnerability (lack of resilience). In 2019, direct economic losses and damage from natural disasters were $232 billion, with 409 total natural disaster events. Only a small proportion of these are currently insured – the so-called ‘protection gap,’ which at first sight presents a significant business opportunity for insurers. In 2019, for example, worldwide economic damage from flooding was $82 billion, with only $13 billion of that being insured, a trend that has held steady for the past twenty years (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:

(Source: Aon, via The Financial Times 2020)

Rising physical risk levels are already threatening insurability as well as the affordability of existing coverage. Higher claims costs will require a higher premium, which may jeopardize affordability. The higher the projected climate warming, the more extensive the implications for the sector. Simply put, as the CEO of AXA, a French insurance firm, comments, “A +4℃ world is not insurable.”

In addition, disasters themselves are highly unpredictable and difficult to forecast, creating a situation in which insurance companies suffer from “the inability to assess and quantify probabilities of predicted losses with sufficient precision,” meaning that insurers are often reluctant to insure disaster risks without a very high premium or cost to the customer. Hurricane Andrew, a category five hurricane which struck Florida in 1992, caused the failure of at least sixteen insurers the following year due to the high claim pay-out. Although the industry has come a long way in terms of assessing their exposure to today’s risks, current modelling tends to ignore future risk trends. Swiss Re, a Swiss reinsurance company, cautioned that “insurers should be wary of historical loss records in understanding today’s state of the socio-economic environment and climate. Averaging out over a past spanning multiple decades can lead to distorted risk assessment.”

Specifically concerning insurance premiums, one issue of increased climate risk is the long-term business model resilience of the insurance sector and the potential inability to set premiums high enough to account for the risk and loss in revenue. Premiums might indeed be expected to rise on average, as markets continue to fluctuate in response to climate change (Westcott et al, 2020). This is partially due to the nature of floods— as a concentrated and correlated risk, floods require insurers to hold a lot of capital, which in turn requires that they charge a higher premium.

In the United Kingdom, a program called Flood Re offers subsidized reinsurance coverage so that insurers can continue to offer flood insurance to home insurance buyers in high risk areas. Analysis of Flood Re via an Agent-Based Model specifically for surface water flooding in London showed how climate change is expected to put pressure on this approach, for it does not present a sustainable long-term solution to flood insurance, as it does not provide any incentives to reduce risks. Several studies have highlighted the need for insurance to support physical risk reduction (Kousky, 2019; Hudson et al., 2019; Surminski, 2018). While implementation is still limited, there are some encouraging signs. For example, the UK’s Flood Re recently announced its support of policy holders in their resilience efforts. The Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance is another example of an insurer engaging with communities around the world to support their understanding of risks and resilience. As society’s risk manager, the sector can help make the world more flood-resilient and prepared for future risk levels– but has missed many opportunities to do so.

Transition Risks

Global economic activity will be radically rebalanced in the decarbonization transition. This will have impacts on investment portfolios, particularly in the context of the devaluation of holdings in carbon-intensive industries, and new investment opportunities in the growth of low-carbon technologies as the world moves to a low carbon economy. A growing number of companies are starting to reflect on climate change and other sustainability criteria in their investment practice and report on it as part of their financial disclosure. However, according to Shareaction, as of 2018, “less than 0.5 percent of assets invested by the world’s eighty largest insurers are in low-carbon investment, despite the insurance sector being highly exposed to its financial risks.” Transition risk is also relevant for the underwriting side of insurance, and some companies have started to limit or exclude carbon-intense sectors from their insurance portfolios. The rating agency Moody reports that “While thermal coal is a relatively large sector, we do not expect large diversified insurers’ thermal coal exclusionary policies to result in a meaningful loss of business.” In general, potential expected challenges in transition risk arise from uncertainty about future regulations and technologies, and the risk of asset-stranding or sudden shifts in operational practices, risk profiles, and insurance needs of companies and sectors.

An interesting example of the impact that this has on the insurance market is the shipping sector, which conveys percent of world trade. A third of current maritime trade comprises of fossil fuels, which will quickly decline. In turn, shipment of biomass, renewable equipment and lithium cargo is expected to rapidly increase, which creates new risks for transporters that will require insurance cover. Additionally, the shipping sector will also have to reduce its own emissions: Current International Maritime Organization (IMO) ambitions require zero-emission vessels by 2030, which encompasses things like the use of lighter materials, greener propulsion devices including wind turbines, and reducing emissions in ship-port interfaces. In response, insurers can help facilitate investment in low-carbon technologies by supporting more effective risk-sharing between vessel owners and charterers. In shipping as well as in other sectors, insurers have the opportunity to help manage these risks for their clients and are thus a necessary and important player in the transition to decarbonization.

Liability Risks

Liability risks exists in two ways: insurers facing litigation because of their corporate practices, and litigation impacting their customers. As of 2019, climate change litigation cases have been present in at least twenty-eight countries around the world, with a majority of cases in the United States. Litigation is increasingly viewed as a policy tool to influence both public and private sector behaviour, but there is a disconnect within the insurance industry surrounding this threat– climate change litigation strategy is not yet embedded in insurer strategy, nor have the risks across jurisdictions and business been assessed to the point of providing input for investment decisions. The evidence of climate change litigation is still at a mostly anecdotal stage, and it is essential that as this evidence continues to develop, research and analysis of climate related liability risk to the insurance industry continues to develop as well.

Climate Change Tests Relationships and Challenges the Current Value Proposition of Insurance

Climate change has, and will continue to have, a profound effect on society as well as on individual businesses. The insurance industry and risk management industry can spearhead the transition to a low-carbon, resilient future by supporting clients in the net-zero carbon transition, aligning risk knowledge with investment decisions, and working with their clients to reduce risk and increase climate resilience. Failure to do so is likely to lead to significant increase in liability risks as well as growing physical risks that threaten insurability in years to come. At stake is also the relationship with customers, regulators, and policymakers– climate risk information is still struggling to find its way into these relationships. This is a missed opportunity, as those customer relationships determine risk levels today and in the future. Decisions taken now influence climate risks, be it in terms of building new infrastructure or homes, locating business parks or manufacturing sites, or choosing suppliers and technologies according to carbon footprints. Therefore, these decisions need to be managed.

This action also requires transparency. The Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has also stimulated new activity by the insurance sector to deepen its existing work on risk modelling in the new context of scenario planning. Importantly, the new wave of reporting that will result in response to the TCFD’s recommendations will not just be used by the sector’s investors but also by the regulatory community as it seeks to understand overall systemic risk.

Insurers have an opportunity to bridge the knowledge gap about climate change risk across both the underwriting and assets sides of their own industry and work towards ensuring exposure to climate risks are embedded into investment decisions. After a disaster or climate shock hits, insurers are an essential player to make sure infrastructure is rebuilt in a low-carbon and climate-resilient way. In addition, our approach to allocating disaster management funds must shift – currently, eighty-eight percent are allocated towards post-event response, with only thirteen percent allotted to pre-event risk reduction and prevention. This process is not sustainable, and the insurance industry is a powerful player to help shift this narrative for society, not only as a responsible sector but also with a view to secure the viability of its own business model.

. . .

Dr. Swenja Surminski is Head of Adaptation Research at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. Her research interests include climate resilience, disaster risk management and sustainable finance. She works closely with industry and policy makers, was appointed Visiting Academic at the Bank of England in 2015 to work on the regulator’s first report on climate change and is chapter lead author of the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment. Prior to her work at the London School of Economics, she worked in the insurance industry for over a decade, specializing in risk management and helping companies adapt to climate uncertainty.

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…