Much of the arguments made by tech firms and part of the decline in antitrust cases over the past couple of decades is that larger firms are able to generate efficiency, which thereby lowers prices for consumers. In your view, this argument does not necessarily pan out because of the long-term harms?

Correct. I do not think that a plaintiff builds its case on short-term price effects. Suppose that instead, the focus was long-term innovation. Google would come back and say, “that is all fine, but it is very speculative. What we want you to focus on, Your Honor, is this lower price in the instance period.”

I think that [tech firms] would actually have to show that the price is being lowered or that there is some kind of short-run benefit to offset the long-term innovation harm. On the Google front, when it comes to self-preferencing and search, there have been studies that have shown that Google is actually degrading the quality of search by injecting its own affiliated, inferior properties at the top of the rank. The way that economists have figured this out (this was a piece co-authored by some Yelp data scientists) is that they found that the click-through rate–which as the name suggests is how often users click through the links after they are served up by Google–falls when Google feeds you its affiliated properties. The click-through rates increase when Google is tricked into reverting back to its organic algorithm. This is a long way of saying that I actually think that there are short-term harms. They are just not price harms. We have a short-term quality degradation. The more important harm is this innovation harm. We will ultimately see a judge engage in that balancing, and it is not going to be easy.

A lot of people like you are also concerned about these sorts of harms, which is why the House subcommittee and the EU commissioner have suggested divesting certain operations from the firm’s main line of business to preserve competition. Do you believe breaking up these big tech firms is necessary to preserve competition?

It is not technically necessary because there is a less invasive approach that would get at the same outcome. I know that is probably going to upset all sides when I say that, but let me see if I can do this justice. Would divestiture solve the problem? Yes. If Google is giving preference to its own search properties and Amazon is giving preferences to its own merchandise, and if you forced those platforms to spin off their edge properties so that some other company held it, you would solve the problem.

But, the way that you phrased the question was a trick. As someone who gets deposed for a living, I cannot help picking out what you said: “Is it necessary?” It is not technically necessary to the extent that you can solve it with a non-discrimination regime. Right now, there is a big controversy in policy circles as to whether or not a non-discrimination regime on its own would work. But what I have in mind and what the House-majority Report picked up as their second remedy is the idea that Google and Amazon and these other vertically-integrated platforms would be subjected to a non-discrimination regime.

In layman’s terms, a non-discrimination regime means if an independent felt that it had been discriminated against in carriage either by Google or Amazon, it could lodge a discrimination complaint in front of some neutral third-party factfinder like an administrative law judge. That judge could make a determination as to whether or not the carriage or the treatment was in fact motivated for discriminatory reasons. If so, the judge would come up with the proper relief.

To be clear, right now it is legal for these tech companies to discriminate against different vendors, or is this a legal grey area?

That is the million-dollar question, right? The Department of Justice (DOJ) complaint did have a few paragraphs related to self-preferencing in search. If you ask someone at the DOJ, they might tell you that they actually think it is illegal, and that it is in violation of antitrust laws. But since it has been going on for over a decade, I am sure Google is acting as if it is legal until proven otherwise, so they are just going to continue to do it.

. . .

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

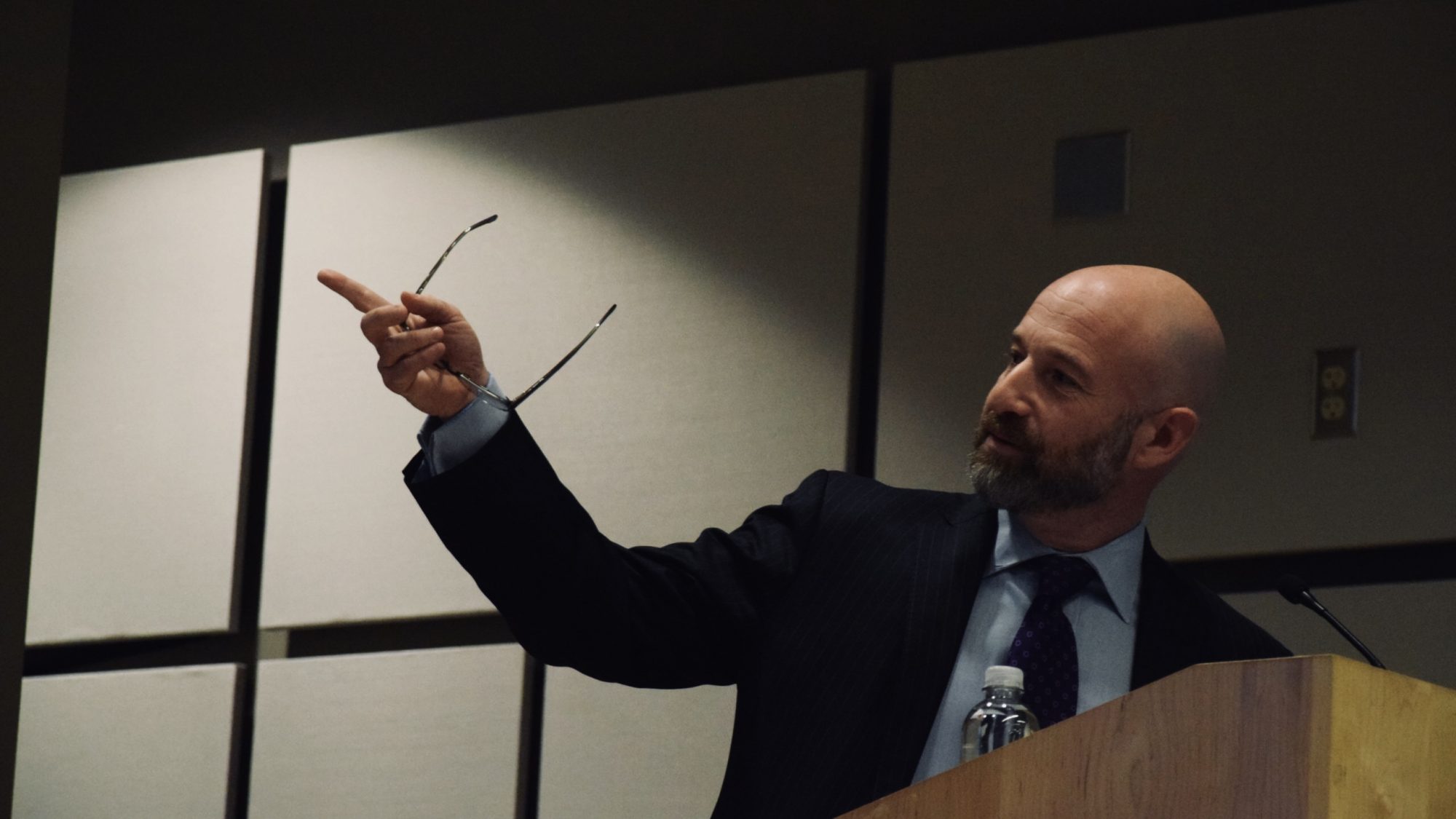

Dr. Hal J. Singer is a managing director at Econ One Research, a senior fellow at the George Washington Institute of Public Policy, and an adjunct professor at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business. He is a co-author of the e-book The Need for Speed: A New Framework for Telecommunications Policy for the 21st Century (Brookings Press 2013) and co-author of the book Broadband in Europe: How Brussels Can Wire the Information Society (Kluwer/Springer Press 2005). Dr. Singer has testified before Congress and has been widely cited by courts and regulatory agencies, including the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Department of Justice. His Twitter handle is @HalSinger.