Title: When “Pariahs” Go Green: Energy Transitions in the Middle East and the Biden Administration

Energy transitions will materially affect US foreign policy in the Middle East. They will spur a Middle Eastern pivot to Asia in search of oil demand security and more diversification into petrochemicals. Renewables will be used to satisfy skyrocketing domestic energy demand, safeguard oil export capacities and develop new forms of energy exports. Even if successful rent income of the region’s rentier states will diminish and the need for taxation will alter the existing social contract. As the global energy mix transitions towards renewables, technology is becoming strategically more important than location and the geopolitical relevance of the region will decline.

Oil Demand Shocks and US Foreign Policy

US foreign policymaking in the Middle East tends to look at itself in the rear-view mirror. Reliable oil supplies against American security guarantees loom large in its calculus while human rights take a back seat. The Trump administration represented this formula in its extreme. Joe Biden has promised to return to a more balanced version of it, calling Saudi Arabia a “pariah” for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. He has curtailed military assistance for the Saudi campaign in Yemen, while maintaining cooperation with the Kingdom, most notably on containing Iran. What is underappreciated, however, is how energy transitions will alter this compromise formula in the future.

The unconventional oil revolution has already reduced US crude imports. More impactful than this supply shock could be a demand shock: propelled by climate mitigation efforts and new technological opportunities such as electrification of transport and green hydrogen, renewable energies will grasp a larger share of the global energy mix. Middle East oil exporters have taken note of this. In its 2019 IPO prospectus, Saudi Aramco advised that, by the mid-2030s, a peak in global oil demand might affect its business prospects.

Gulf oil exporters lobby against international climate mitigation efforts that they regard as overly ambitious. Meanwhile, they seek to adjust to an energy transition world via the following measures: (a) securing hydrocarbon markets that will be less affected by the transition (e.g. petrochemicals), (b) using renewables to satisfy the growing domestic energy demand that threatens oil export capacity, and (c) exploring export options of renewable energies in the form of electricity or green hydrogen, taking advantage of the ample solar radiation and open spaces in their countries.

Petrochemicals and the Middle Eastern Pivot to Asia

The first measure is already extensively practiced; some Gulf countries have developed into global production hubs for petrochemicals. A Tesla might not need gasoline, but contains plastics like any other car, as do major appliances computers, PlayStations, and other consumer items that show unabated demand growth, especially in emerging markets. As the consumption of these goods does not cause emissions, they are less controversial in terms of climate change negotiations (that they cause a lot of plastic waste and recycling needs is another matter). Renewables are also unlikely to replace hydrocarbons in heat-based appliances in heavy industries any time soon (e.g. cement, aluminum, and steel). Batteries cannot provide the high energy density that is required to fuel ships, planes, and heavy trucks. Here, oil demand destruction from renewables could only come via other technologies such as green hydrogen that the German government and the EU sponsor prominently. However, green hydrogen is not as developed yet, and its chances of success are clouded by high conversion losses. On the other hand, there is a trend towards cleaner hydrocarbon fuels within some market segments, such as shipping that represents seven percent of global oil demand. The reduced-sulfur marine fuel standards from the International Maritime Organization (IMO) that took effect in 2020 have prompted a shift from extremely polluting fuel oil to less damaging diesel products. This requires more advanced deep-conversion refining. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have developed petrochemical industries, whereas oil exporters that have not, such as Kuwait, Libya, or Iraq are less well-positioned to cater to these markets. Even after peak oil demand, not all is lost for MENA oil exporters. Their commercial attention will pivot to Asia and other emerging markets where oil demand will likely be more resilient.

Renewables to Safeguard Oil Export Capacities

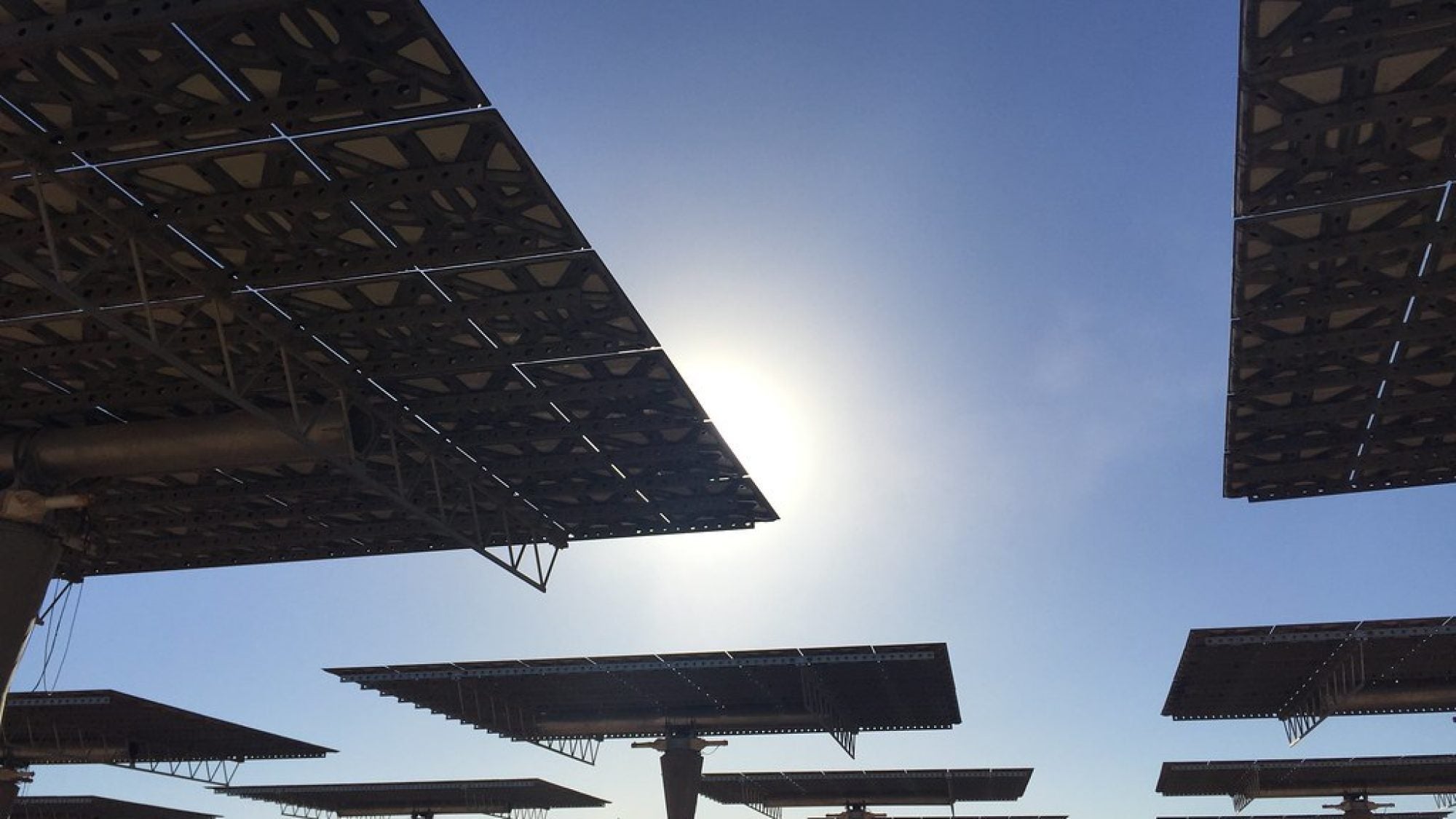

The second adaptation option is an urgent requirement for Gulf oil exporters. Their energy consumption has been skyrocketing as a result of economic growth, heavy industries, and sprawling car-centric cities. It could threaten oil export capacity in the long run if left unchecked. To reduce the burning of fuel oil in power plants, Gulf countries seek to develop more domestic natural gas resources and turn to alternative energies. The UAE and Iran are the first countries in the region that operate nuclear reactors for civilian purposes. Abu Dhabi has identified renewables as a strategic sector and has hosted the International Renewable Energy Agency since 2009. Ambitious expansion plans for renewable energies have been announced by the UAE and Saudi Arabia. However, they must be taken with a pinch of salt because these initiatives have been toned down in the past or continue to remain behind expectations. Yet the region might develop from a global laggard into a leader, given the dramatically reduced costs of solar-generated electricity in the region. They belong to the lowest in the world. Renewable power generation is now cost-competitive with that fueled by hydrocarbons. This leaves intermittency, storage solutions, and grid management as the main challenges for its more rapid expansion. Like elsewhere, energy mixes in the Gulf will include more renewables. The interest in commercial and technical cooperation is growing.

Exporting the Sun?

The third adaptation option is enticing, but tricky. Then Saudi oil minister Ali al-Naimi remarked in 2015 that one day, Saudi Arabia could export electricity from renewables instead of oil. However, this scenario is not very likely. Compared to oil, solar and wind power are more evenly distributed across the globe. They do not represent the same scarcity value and thus will not provide oil-exporting regimes with the same amount of rent income. Electricity transportation over thousands of kilometers also turns uneconomical with increasing distance because of transmission losses. Having said that, there will be opportunities in regional electricity trade and grid integration. Saudi Arabia also jumped on the green hydrogen bandwagon and announced a related $5 billion investment in its futuristic NEOM city that is currently being built in the north of the country. Oil and gas will not be the only energy exports of the region going ahead.

Geopolitical and Domestic Changes

As the global energy mix transitions towards renewables, technology is becoming strategically more important than location. Energy systems as a whole will change: their infrastructures, regulations, and markets, not just the source powering them. The relative importance of commodities will decline and will partially shift to other raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals. These materials are located in other regions like South America, China, and Congo, and can be recycled after use, which might limit the need for continuous production increases once a certain global stock has been accumulated. Geopolitical interests and possibly conflict will gravitate towards such regions and away from the Middle East during the process of renewable energy transitions.

Energy transitions also augur domestic changes. The social contract of the region’s rentier states is “no taxation and no representation.” Political acquiescence is bought with services, public sector jobs, and welfare payments. Lower oil revenues threaten this social contract. Oil demand will not disappear overnight and Gulf countries are the lowest cost producers with the lowest life cycle emissions. They will be the last man standing in a peak oil demand world. Lack of global investments to replenish reserves might even lead to a temporary boom in oil prices along the way, a feast before the famine, but the basic challenge is there. It explains the various initiatives for economic diversification that oil exporters are undertaking.

The decentralized features of renewables have prompted hopes that energy transitions could strengthen political participation, enabling local ownership of energy resources by communities and “prosumers.” Such hopes for “energy democracy” might be overblown in the case of the Gulf countries, because here centralized large-scale utility applications of renewables dominate. Yet the basic argument remains valid and might lead to more subtle changes: labor and capital will capture most of the remunerations along renewable value chains, not the owners of a particular resource. New economic actors—such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) rather than centralized utility companies—might emerge, and articulate political interests over time. As former rentier states need to take recourse to taxation to offset declining oil revenues, they are unable to maintain their part of the old social contract. The lack of political participation will be less acceptable than before. Renewable energy transitions could engender socio-political change as well.

Quo vadis Middle East? Quo vadis US and Europe?

What does that mean for the Biden administration and the oil-centered compromise formula of US Middle East policy that was mentioned in the beginning? Peak oil demand and energy transitions will put pressure on the region’s autocrats who will repress dissent even more forcefully. Calls for human rights interventions will increase at a time when the realist argument for cultivating ties—securing oil supplies—carries less urgency than before. In their quest for oil demand security, Gulf countries will turn towards emerging economies in Asia where they export two-thirds of their oil already. Customers there have the additional advantage of refraining from nagging human rights inquiries. The quid pro quo between authoritarians is already on full display with the deafening silence of Middle Eastern rulers in the face of Chinese repression of its Muslim Uyghur population. Asian countries are also well positioned to assist Gulf countries in their energy transitions at home. However, it is here that considerable openings exist for the United States and its European allies as well, ranging from renewable export options such as green hydrogen, to assistance for grid integration and desalination, to nuclear cooperation, such as the 123 agreements that the United States has signed with the UAE and negotiated with Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Ultimately, energy transitions will be a target as well as a means of foreign policymaking and the United States, as well as Europe, must adapt.

. . .

Eckart Woertz is director of the GIGA Institute for Middle East Studies in Hamburg and professor for contemporary history and politics of the Middle East at the University of Hamburg. Previously he held positions at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), Sciences Po in Paris, Princeton University, and the Gulf Research Center in Dubai. Before these academic posts, he worked for banks in Germany and the United Arab Emirates in equity and fixed income trading.

Image Credit: IRENA (via Creative Commons)

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…