Title: Biden Could Be a Climate Change President, and COVID-19 Is Only Part of the Story

COVID-19 is just one of many factors animating the Biden administration’s climate agenda. Through the fulcrum of climate action, the Biden administration wants to satisfy its political base, re-industrialize America, provide justice for communities affected by systemic racism, out-compete China in everything from semiconductors to electric vehicles, and revive American diplomatic and moral leadership.

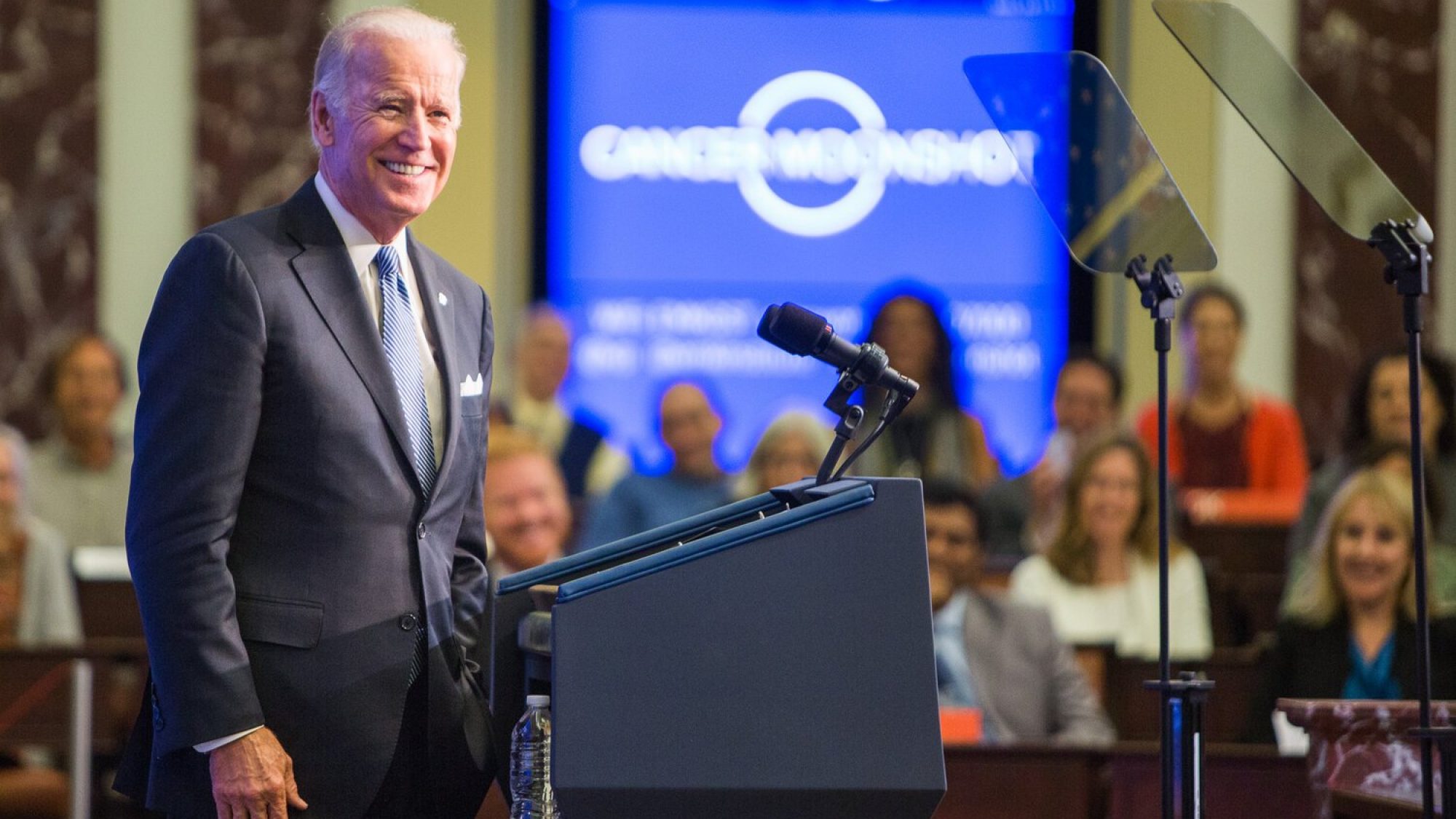

Just a few months into his presidency, Joe Biden is already the most ambitious climate president in history. On his first day in office, he signed five climate-related executive orders. A week later, during “Climate Day,” the White House unveiled a number of additional initiatives, pledging to—among other things—ratify the Kigali Amendment on hydrofluorocarbons, establish a White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, create a Civilian Climate Corps, and reach carbon-free electricity by 2035. Then, on March 31, the administration announced the American Jobs Plan, which includes over $1 trillion in climate-related investment—the largest such commitment in history.

Joe Biden has emerged as a climate change president, and COVID-19 is only part of the story. In addition to a global pandemic, events such as the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, climate marches, and increased congressional interest have all pushed climate to the heart of an ambitious, even “radical,” presidential agenda. Through the fulcrum of climate-related investment, Biden wants to re-industrialize America and rebuild the middle class, provide justice for communities affected by systemic racism and environmental inequities, and out-compete China in everything from semiconductors to electric vehicles.

Though it is tempting to link all of Biden’s current climate ambitions to the COVID-19 moment, there was a time when climate advocates feared the global pandemic would halt the gathering momentum on the issue. In September 2019, New York was the center of the second-largest global protest in history, when Greta Thunberg led as many as 250,000 New Yorkers in a “climate strike.” Whether it is the result of such activism or more visible evidence of climate change impacts in people’s lives, support for making climate change a “very high priority” was at its highest point ever by late-2019, with twice the popular support as at the start of Obama’s first term.

The combination of grassroots activism and broad public support set off a race in the Democratic presidential primary, as candidates released increasingly ambitious climate plans. The first iteration of Biden’s climate plan, though far more ambitious than anything Clinton or Obama had ever put forward, was savaged by climate advocates early in the campaign. He received just 75 out of 200 by the youth-led Sunrise Movement, 72 out of 100 by Greenpeace, and 26 out of 48 from Data for Progress, a progressive polling firm. The Biden campaign team saw this as a problem, and promptly updated his climate agenda for the general election to reflect progressive priorities more closely. In particular, it increased the size of pledged climate spending, adopting a 2035 zero-carbon electricity target and a 2050 whole-of-economy net-zero target.

Biden’s climate campaign platform promised a “historic investment” of $1.7 trillion over ten years in a “Clean Energy Revolution,” and has already gone a long way towards that goal with the American Jobs Plan (AJP). The AJP would be three times larger than the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of the Obama Administration and include almost ten times as much climate-related spending—seventeen times as much if clean energy tax credits are included. It includes $174 billion for electric vehicles, encouraging both the supply of American-made vehicles and incentives for consumers, $100 billion in a clean electricity grid, and a range of items for clean energy research and development, technology demonstration, and home-grown manufacturing.

Perhaps just as important as Biden’s elevated climate ambitions, the primary campaign forced him to adopt a new framing of the issue, steering away from environmentalism and towards an economic and social justice lens. Though Biden did not endorse the Green New Deal bill, introduced in 2019, he regularly repeats the refrain that climate change policy is all about “jobs, jobs, jobs.” This reflects a spirit of intersectionality, explicitly tying climate to social and economic reform. COVID-19 and the BLM protests further exposed the deep inequities in American society, particularly around race. As a result, it became increasingly important politically for the Biden campaign to connect other priorities, and especially climate change, to social justice issues.

Biden and his administration have prioritized “environmental justice” issues, both in executive orders and the AJP. Environmental justice refers to the distributive effects of environmental policies, particularly the disproportionate impacts of polluting industries on low-income communities and communities of color. Approximately six percent, or $138 billion, of the AJP can be classified as targeting environmental justice. The plan is also consistent with President Biden’s Justice40 initiative, which orders forty percent of all benefits from federal climate action go to disadvantaged communities. Again, this reflects the newfound clout of the progressive wing of the party, and its ideological focus on issues of social justice and inequality.

Climate is also a top priority for Congressional Democrats. This is a marked difference to Obama’s presidency, who wanted prioritize climate change but found congressional support to be shallow at best. Democrats not only hold a slim majority in both chambers, but many Congressional Democrats have also spent the last four years fleshing out a series of climate change proposals that they hope will feature prominently in Biden’s overall agenda. For example, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer wants every car manufactured in the United States to be electric by 2030 and every car on the road to follow suit by 2050, in a half-a-trillion dollar plan first proposed in 2019 that bears strong resemblance to provisions in the AJP. Last year, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis released its Climate Crisis Action Plan, a 547-page behemoth that also mirrors much of Biden’s agenda. In fact, many Democrats complain that Biden’s AJP does not go far enough, arguing its headline figure should be closer to $10 trillion, as outlined in the so-called THRIVE Agenda.

These broad changes were essentially in motion well before COVID-19 struck. Where the pandemic seems to have had an unambiguous effect is in macroeconomics of all places. The pressure for large government spending in response to the crisis has provided a window of opportunity for the president’s ambitions. As evidenced by the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan, the age of austerity appears to be over. A new era of “Bidenomics”—defined by cash benefits, middle class job creation, and public investment in innovation and industrialization—is poised to take its place. While this shift reflects debates that have been taking place since at least the 2009 financial crisis, Republicans’ willingness to pass nearly $3.5 trillion in total stimulus spending shows how little sway the austerity ideology now holds in American politics.

While COVID-19 has certainly delayed short-term climate actions, the crisis has sparked a debate over the role of public investment and government intervention in responding to societal challenges, especially climate change. Arguably, there has never been more momentum behind climate action: 126 countries have made promises, pledges, or plans to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Several countries and institutions have borrowed Biden’s “Build Back Better” language to describe their green recovery investments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is not yet clear how seriously to take this rhetoric. Just six countries have enshrined their targets into law, and only seven countries—all European—have spent more than one percent of GDP on green recovery investments.

All these developments are overshadowed by an increasingly tense relationship with China. Easily the world’s largest emitter and, ironically, manufacturer of clean energy technologies, China is one of the countries to have recently announced a net-zero target with few accompanying details. As with the 2015 Paris Agreement, it will likely use further climate actions as a bargaining chip in US-China negotiations on a raft of issues. Competition with China is also a growing justification for actions at home. In his speech announcing the American Jobs Plan, for example, Biden remarked that “we have to improve our infrastructure…China and other countries are eating our lunch.”

Climate change sits at the intersection of multiple forces pressing upon the Biden administration, of which COVID-19 is but one. Progressives continue to drive a historically ambitious agenda across a range of issues, and climate change is both increasingly popular in the electorate, and even more importantly, prioritized by an impatient Congress. COVID-19 has dramatically shifted the Overton window on stimulus spending, particularly as it relates to investments in green or climate-related infrastructure. Internationally, growing momentum on climate is tempered by the increasing fractious relationship between the world’s two superpowers, and largest emitters.

More generally, success will depend on his ability to improve the lives of everyday Americans, to credibly prove that his government was responsible for the changes, and to avoid being dragged into crises that distract from this agenda. On climate change, Biden will have to live up to promises of jobs, just transitions, and justice, even as his administration aims for historic cuts to emissions.

As Biden likes to say, “You can define America in one word: possibilities.” So far, it is all too possible that Joe Biden will be remembered as America’s first climate president. It is unlikely he will be the last.

. . .

Lachlan Carey is an associate fellow with the CSIS Energy Security and Climate Change Program. His research interests include the geopolitics of energy, climate change policy, and international trade. Mr. Carey was previously a consultant with the World Economic Forum and before that worked in the Australian Treasury Department in Canberra. He holds a master’s in public affairs from the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University and a Bachelor of Commerce (liberal studies) from Sydney University.

Nikos Tsafos is an acting director and senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). His research interests include natural gas, the geopolitics of energy, the future of mobility, and the energy transition more broadly, especially the interplay between energy consumption, economic growth, and greenhouse gas emissions. Nikos has advised companies and governments in over 30 countries on some of the world’s most complex energy projects, and his experience includes market analysis, strategy formulation, due diligence, and support for commercial negotiations and project development.

Image Credit: Eric Haynes, Creative Commons License

Recommended Articles

This article examines the EU’s cyber diplomacy in Moldova’s parliamentary elections from September 28, 2025, which marked a new chapter in the bloc’s cyber diplomacy. Drawing on analysis of Russian…

Export controls on AI components have become central tools in great-power technology competition, though their full potential has yet to be realized. To maintain a competitive position in…

The Trump administration should prioritize biotechnology as a strategic asset for the United States using the military strategy framework of “ends, ways, and means” because biotechnology supports critical national objectives…