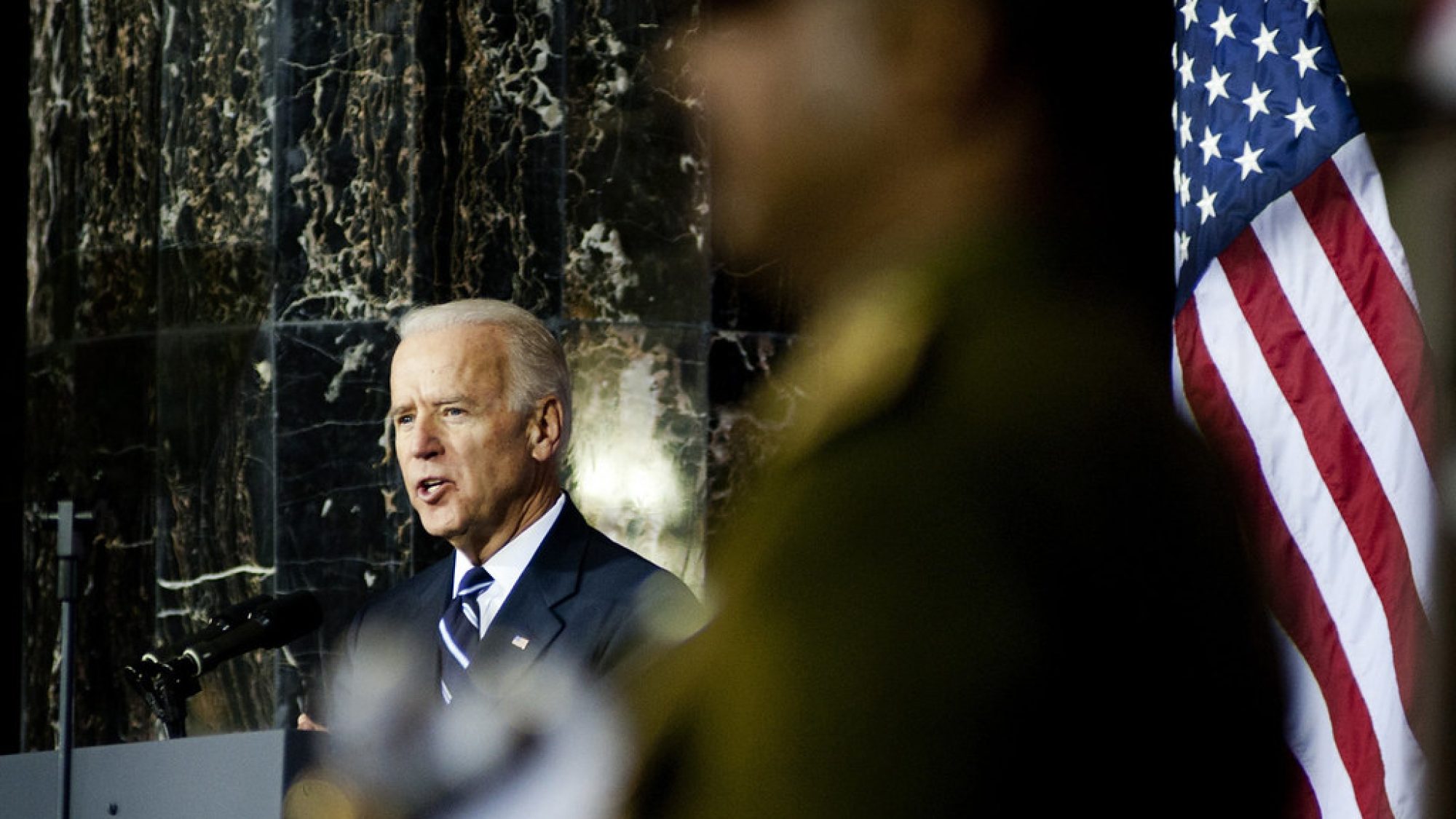

Title: Unraveling US-Middle East Relations Under President Biden With Dr. Trita Parsi

Change is rapidly unfolding in the Middle East. Iran Nuclear Deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) negotiations are restarting, Israel’s relationship with its Sunni neighbors is shifting, and the United States is reconsidering its involvement in the region. Dr. Trita Parsi, executive vice president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, joins GJIA to discuss how the Biden administration is navigating these newfound trends and what the implications of US policy will be going forward.

GJIA: I want to begin by discussing Iran, specifically the Iran nuclear deal. Talks will restart in Vienna on November 29th to discuss the United States potentially rejoining the deal. What do both sides need to do to reach an agreement?

TP: In my view, there is a need for greater flexibility and creativity on both sides. On the Iranian side, I think there has been an adoption of greater realism in the sense that not all of Trump’s sanctions are likely to be lifted. But the sanctions that can legitimately be justified will undermine the sanctions relief of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). And it appears to me that the US team has both understood and shown some flexibility there. This is not surprising, as many of the people in the Biden administration themselves criticized the sanctions on this very ground when they were out of office during the Trump administration. They knew quite well that the intent of the sanctions was to make it next to impossible to go back to the JCPOA.

On the American side, there is a need to recognize and address the fact that the JCPOA contains a very significant asymmetrical problem. If the Iranians were to violate or leave the deal, there would be almost instant punishment. There’s a snapback mechanism in the UN created specifically for this, to make sure that sanctions can be re-imposed on Iran very swiftly. If the United States leaves the agreement, however, it is not the US that pays the cost. It is once again the Iranians and the Europeans that pay the cost. That’s exactly what happened when Trump left the deal, because the US did not have any of its own economic engagements through the JCPOA and because no primary sanctions were lifted.

This leaves a situation in which there’s very little faith or comfort knowing that the United States is going to stick to the deal. This is because if any administration comes in that doesn’t like the deal—which means half of the administrations because the Republicans are dead-set against the JCPOA—then there is nothing to deter them from pulling out. Trump has proven that.

Given that, it creates a massive problem on the Iranian side: every time they go into the deal, they give up their leverage, and sanctions get lifted, but the economic benefits of sanctions relief does not come to Iran. This is for a very simple reason: international companies do not care if sanctions are lifted or not, they care if sanctions are lifted long-term. So the United States could lift the sanctions and the Iranians would get no economic benefit, which means the bargain has been invalidated.

What needs to be done now is not to change the deal; this is not about changing what the United States gives and doesn’t give. This is not about whether the Iranians give less or more, it’s about the mechanisms that were put in place in order to ensure compliance only on one side of the equation. These mechanisms were not on the US side, because the international community just assumed that the United States is reliable, which is a very dangerous assumption these days.

Focusing now on the bigger picture with Iran, how do you envision future US-Iran relations? If the nuclear issue is resolved, how do you see the two dealing with other points of friction in their relationship, such as Israel, Yemen, or Iraq? Do you envision a possible realignment where the US and Iran are allies, or are the two countries stuck at opposite sides of a great power competition in the Middle East?

I don’t foresee any realignment. I don’t see the two countries desiring an alliance. This may be a nightmare that folks in Riyadh have had, perhaps in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem as well, but it’s never been in the cards.

At best, what can happen is that the United States and Iran disentangle themselves from each other, meaning that they are not involved against each other in every arena in the Middle East. I think by and large, this would happen almost automatically with the United States withdrawing itself from the Middle East militarily. At that point, they would probably at best have some sort of a neutral relationship. They’re not constantly gunning for each other, but nor are they necessarily aligning and collaborating strategically. The key thing is to make sure that the destabilizing effect of a US-Iran rivalry and enmity is neutralized because it’s been utterly destabilizing for the entire Middle East.

Afghanistan would have looked very different today if, once the Taliban fell, the United States and Iran didn’t start competing against each other. Iraq would be looking very different today and Lebanon would be looking very different today too. Unfortunately, these rivalries—whether it is the United States and Iran or Saudi Arabia and Iran—tend to take place at the expense of weaker countries. These countries become the arena for these types of rivalries at their own cost. It is very detrimental to them, but also very detrimental to stability in the region.

The US strategy of prioritizing direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations has been stagnant for multiple decades. The Trump administration tried a new approach of engaging the U.S’s Sunni Arab allies and negotiating normalization agreements between them and Israel. These agreements satisfy Israel, they satisfy the Sunni nations, and they’re embraced by both sides of the political aisle in the United States. So from a realpolitik perspective, is continuing with the Abraham Accords the only way forward on the Israeli-Arab conflict? And if so, what does this portend for the Palestinian cause?

First of all, in every case, with the potential exception of the Emiratis, the Israelis did not give anything—the concessions came from the United States. That is the case of Sudan, and that is the case of Bahrain. What did Israel have to offer Morocco in Western Sahara? It’s essentially decisions made by Sunni states to get what they can get on their own issues, because they believe that the Palestinian issue has become less potent than it was before. So you have a couple of cases in which some states view their interests as very aligned with Israel, and a much larger number of cases in which the United States is providing all of the concessions, and then an even larger number of cases in which they have not gone through this normalization at all.

What it’s done for the Palestinians is actually set back the prospects for real peace, because at the end of the day, it is a validation in the eyes of Bibi [former Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu] that his strategy of giving nothing on these issues and continuing a creeping annexation will eventually be accepted by the international community.

So in my view, you’re not seeing a dramatic shift, you’re seeing some musical chairs: the United States pulling out and the Israelis seeing the opportunity to pull in further. I have a major problem with this, because I believe that this structure is part of the reason why there’s so much tension in the region. It’s a balance of power game being played, without an actual attempt to resolve the tensions. And it’s an endless game that eventually will lead to a conflict.

The alternative to that is what has been happening in Iraq, in which the Iraqis have been hosting dialogues between the Saudis, Iranians, and Emiratis. It’s actually an effort to really resolve the tensions. I think this Baghdad Conference is a wonderful initiative because for the first time in a very long time, we’re seeing regional states themselves trying to resolve their tensions.

A common argument against this anti-interventionist worldview is that if we leave countries to their own devices, other superpowers will intervene in a worse way than the United States. For example, when the Obama and Trump administrations minimized involvement in Syria, this allowed the Russians to become the dominant power and bolster the Assad regime. With this in mind, can American foreign policy be based solely on whether our actions are right or wrong? Or must we recognize our responsibility to be the lesser evil by intervening in certain countries to prevent a more harmful actor like China or Russia from doing so?

We intervened in Iraq based on lies. You mentioned Russia, the Russians opposed it, they would not have intervened. Which one was the lesser of two evils? The same thing happened in Libya: we intervened, we got NATO, we even got a UN Security Council Resolution (even though it didn’t allow for the intervention) but as soon as we could we turned it into a regime change effort. The Russians and the Chinese opposed it. Which one was the lesser of two evils? I think our interventions in the Middle East have been disastrous, and I do not see that every time we intervened, had we not intervened, someone else would have stepped in.

Even though the Russians did step into Syria, and I think they did play a very important role in keeping Assad there, the alternative is presumed to be that Assad would have fallen, and Syria would have been a wonderful democracy right now. There’s very little to suggest that, because in Libya, Gaddafi did fall, and there’s nothing left of Libya.

I think if we pursue a foreign policy in which we are not trying to dominate various regions militarily, we will see exactly what has happened in the Baghdad Conference, which is that these states realize their best option is actually to try to resolve their tensions with each other diplomatically. Again, it may or may not succeed. But as long as we’re willing to come in there with some sort of a security umbrella, which is a very unbalanced one, we actually disincentivize countries from resolving tensions on their own.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

…

Dr. Trita Parsi is the executive vice president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and recipient of the 2010 Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order. He is an acclaimed expert on U.S-Iranian relations and Middle East geopolitics, authoring several books including the award-winning “Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States.” His Twitter handle is @TParsi.

This interview was conducted by Editorial Assistant Uri Guttman.

Image Credit: Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

More News

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…