Title: Replacing Consociationalism with a Meshwork Model in South Sudan

Recently both scholars and mediators have called for a different approach to resolve the interethnic conflict in South Sudan. Foremost among these calls, with the most extensive deconstruction of the consociational approach, is the High-Level Experts’ seminar that was held in Juba, South Sudan, on November 5-6, 2019, which brought together think tanks, the Government of South Sudan, UNDP and other stakeholders to assess the implementation of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). The seminar also coincided with the first anniversary of the R-ARCSS since it was signed on 12 September 2018 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

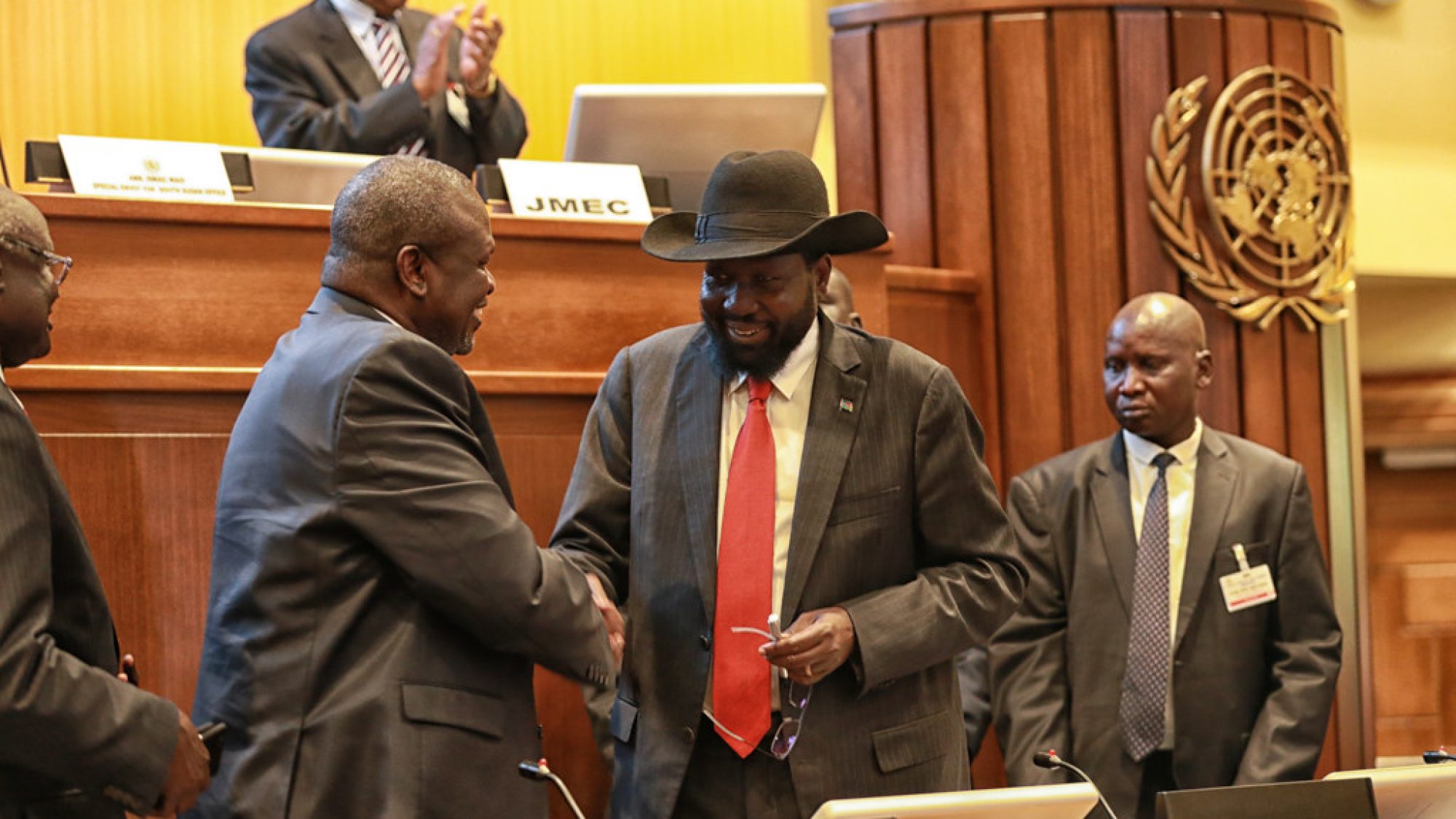

The R-ARCSS framework was designed to embody structural reforms aimed at transforming the politics, military formations, economy, and security architecture of the Republic of South Sudan. I was very much honored to be part of the lead experts’ team advising senior government officials and other interested parties during the seminar as a response to South Sudan’s increasing interethnic conflict and rising humanitarian catastrophes. Strategic dialogues that ensued thereafter drove President Salva Kiir and the First Vice President Dr. Riek Machar to adopt innovative approaches towards nationhood and stability, resulting in the inauguration of the South Sudanese Parliament in August 2021. The appointment of a female Speaker of the National Legislative Assembly was commendable of the two leaders and symbolized a victory against prevailing political biases as well as the revitalization of the peace agreement. Despite these constructive steps, post-war South Sudan may turn out to be more entrenched in civil conflict and political uncertainty than anticipated when the country seceded and attained independence from Sudan in 2011.

South Sudan’s ‘intractable consociationalism’ is remarkably recognized, both in scholarship and policy praxis. In the scholarly world, ‘consociationalism’ can be defined as “elaborate techniques and tools that make ethnicity the core building block in addressing conflicts and politics in a deeply divided society.” In this view, consociationalism is nothing but an extension of Arend Lijphart’s ‘politics of accommodation’ tactics to ethnic conflict and national politics. Political scientists view it as a strategy for analyzing the distribution of power in economic, cultural and political structures, particularly in ethnically divided societies. This viewpoint is based on the idea that a divided society can attain inclusivity and, hence, political stability through an ‘elite cooperation’ strategy, and is meant to ensure proportionality in representation, to build a coalition of community leaders, and to promote collective good. A fundamental difficulty has been that the theory of collective good rarely benefits everyone in the society because self-interested individuals who form part of the elite cooperatives in consociational arrangement are more often concerned with individual needs. Moreover, in what I have previously coined as the ‘clash of classification’, consociational arrangements seem to generate social dilemmas. The social dilemmas, hence, ‘consociational social dilemmas’ (CSDs) create a clash between individual interest (elite cooperatives) and collective good (general population). As such, consociationalism, with its self-interested social ‘profiteering’ breeds cyclic political violence, making it difficult to resolve conflict in ethnically divided societies such as South Sudan.

Thus, rather than being blind to the trappings of CSDs risks, the elite cooperatives in the country must ‘unlearn’ the outdated approaches to ‘learn’ alternative models of conflict resolution. Akin to what Ludger Helms and his colleagues have coined ‘de-consociationalism’, escaping CSDs risks may mean changing from the current consociational democracy to centrifugal forms of governance guided by what Artur Escobar referred to as the political ecology of difference. The political ecology of difference applies the logic of a nonhierarchical ‘meshwork-like’ structure – defined as a self-organizing, decentralized, nonhierarchical, and anti-domineering model of resolving conflict in ethnically divided societies – to create a political system with the ability to counter political and identity hegemony. Nevertheless, the intractability of ethnic conflict in South Sudan and the humanitarian catastrophes has made it no easier to sustain peace agreements, including the R-ARCSS, nor has it resolved the controversy over risks associated with consociationalism.

Risks and Complexes of Consociationalism

Lijphart’s proposition equating consociationalism with ‘politics of accommodation’ is relevant to South Sudan’s current political-security situation. Here, the article will discuss three major sources of CSDs risks and complexes starting with the so-called ‘new deal peace agreement’ mooted in 2021.

The New Peace Deal, 2021

In 2021, the ‘elite cooperatives’ invented what is popularly known as the ‘new deal peace agreement.’ The new deal precedes the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (R-TGoNU) that was established on February 12, 2020. Although R-TGoNU has demonstrated signs of progression in governance restoration, the exclusive focus on the two leaders—President Salva Kiir and his deputy Dr. Riek Machar—reflects the deep-seated risks associated with CSDs. It should be noted, though, that the risks of CSDs are not limited to a power struggle among the elite cooperatives. They are also engraved in the concept of ‘autochthony,’ or who belongs where. With the politics of ‘autochthony,’ individuals or ethnic groups claim to belong to a geographical space more than others on the basis of a naturalized claim to a collective territory. The obsession with the politics of autochthony, especially in the context of a fragile democracy, can be instrumental in determining who accesses consociational power-sharing benefits. Autochthony can become a dangerous phenomenon to statehood, nationhood, or even national unity in situations where those who believe they are the true ‘sons’ and ‘daughters’ of the soil demand a purification of citizenship.

Yet, with murky territorial boundaries in South Sudan, just like any other country in Africa, the question of who belongs and who is an outsider is dynamic. In the country’s Eastern Equatorial State (EES), for example, the sedentary Acholi and Madi claim ancestry to the land and view the pastoralists (mainly the Dinka, Toposa, Nyangathom and Jie) as intruders. It is this cultural claim to ancestral land that contributes to seasonal violent confrontations between the sedentary and pastoralist factions in areas such as Magwi, Torit, Nimule and Kapoeta. A number of factors have been studied contributing to this land attachment behavior, including, the notion of ‘belongingness.’ The complex idea of ‘belonging’ more than others has been exploited by elite cooperatives in South Sudan to justify the consociational power-sharing model. Yet, what counts in consociationalism is not necessarily who is born from the soil, but rather who knows whom through political connections between the ethnic entrepreneurs and elite cooperatives.

R-ARCSS, 2018-2020

In South Sudan, peace agreements are usually a domain for the political elites and military generals who negotiate, sign, and benefit from consociational power-sharing arrangements. This arrangement perpetrates exclusive policies, leading to political payoffs for insurgent violence and turning the peace process into the pursuit of individual interest at the expense of collective good for nationhood and statebuilding. This was the case in the downfall of the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Although the R-ARCSS achieved certain milestones, including the reappointment of Dr. Machar as the First Vice President on February 22, 2020, there are unresolved issues, including state boundaries and security arrangements. The conflicting view of how security arrangements ought to be structured in South Sudan remains a risk factor in the peace process because it reflects a lack of trust among the leading protagonists. In line with the conception of CSDs risks and complexes, this power struggle has remained the defining feature of South Sudan’s peace processes. Both national and international stakeholders attending the November 2019 seminar in Juba concluded that the power struggle was responsible for the recurring risks associated with the CSDs, including 1) the decentralization of decision-making; 2) regional biases and the supply of external military forces in favor of the incumbent president Kiir; and 3) risks of expanding the peace process beyond the SPLA and the SPLA-IO.

ARCSS, 2015-2016

Frustrations generated by perpetual CSDs persisted until the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS) was signed on August 17, 2015. As was expected, in 2016, the ARCSS came under attack through the eminent factional fighting that broke out in Juba between the SPLM-IG and SPLM-IO (taken from a personal interview with SPLM-IO Representative on November 28, 2019). In what has been seen to be the major source of CSDs, Dr. Machar insisted that a federal arrangement be agreed upon as part of a final peace agreement, while President Kiir’s government maintained that the matter should be handled through the constitution-making processes. Under the disguise of territorial federalism, South Sudan’s elite cooperatives retained access to the levers of state power with the aim of carving out ethnic identities as a platform for political and military mobilization. The consociational model has prompted skewed beneficiation from the system with the common narrative of victimization legitimizing violence against ethnic ‘others.’ It is therefore plausible to argue that the politics of ‘ethnic otherness’ is driven by a desire to control the clumsy system of politico-military patronage currently in place.

It is evident that politics of manipulation, military patronage and fake autochthony are inseparable contributing factors to CSDs. As such, the tendency of consociationalism to evoke CSD risks has prompted anti-consociational theorists led by Paul Dixson to cast doubt on the ability of consociationalism to deliver peace in South Sudan’s complex network of ethnic groups and external actors.

Therefore, the proposed ‘meshwork’ model of this article is premised on the idea that formal and negotiated institutions of power-sharing currently in place in South Sudan are insufficient and incapable of overcoming elite self-interests. Hence, can a ‘meshwork’ model overcome these risks and complexes?

Let’s Try the Meshwork Model

Derived from Artur Escobar’s political ecology of difference, the ‘meshwork’ model deals with the economic, ecological, and cultural conflicts that arise from control over a resource or power assigned to individuals or institutions. The framework calls for the re-embeddedness of individuals and groups while at the same time acknowledging the complexity of the various relations across different levels of society. In countries with significant ethnic diversity such as South Sudan, the model presents the possibility of reconstructing an alternative political world by recognising societal diversity. Contrary to the ethnic or individual hegemony characterizing consociational arrangements, the ‘meshwork’ model ensures power and authority are distributed across different tendrils of the society.

Accordingly, this network can be conceptualized as a self-organizing, decentralized, and nonhierarchical meshwork that applies a nonlinear logic in resolving conflict in deeply divided societies. Additionally, rather than forming a pyramidal political structure (symbolic of consociationalism), the ‘meshwork’ model creates an umbrella that allows all individuals and groups to coexist and contribute to statebuilding. While consociationalism embodies hierarchies (centralized control, capitalistic structure, ranks and tendency toward domination by the elite cooperatives), the ‘meshwork’ model presents a tree-like structure. In this approach, the logic of resolving conflict rests on addressing the various branches of the tree (economy, ecology, politics and culture), akin to what Escobar calls “naturalization and universalization of cultural constructs.”

In conclusion, consociationalism, as Arend Lijphartian puts it, represents ‘politics of accommodation,’ within which elite cooperatives have instrumentalized the predatory motives of the main actors in South Sudan. The implication is that contrary to Lijphart’s idea of representation in the consociational model, representational power-sharing is not always the solution to ethnic conflict.

The suggested ‘meshwork’ model for South Sudan and other countries experiencing sharp ethnic divisions offers an inclusive space, where elites and local groups can spontaneously compete, cooperate, diverge, or join to defend their space and identity. It is, however, important to note that the political ecologies of difference or sameness are not mutually exclusive; both can occur at the same time in a particular cultural setting. Therefore, in applying the logic of meshwork in resolving conflict, analysts, diplomats, and mediators are required to understand the extent of the network and patterns of ethnic diversity before any intervention.

. . .

Francis Onditi is associate professor of conflictology & Dean, School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Riara University, Kenya. He was recently enlisted as a distinguished research author and professor of research at the Institute for Intelligent Systems (IIS), University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is the 2019 recipient of the AISA Fellowship awarded by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), South Africa.

Image Credit: Flickr; UNMISS; Creative Commons License 2.o

Recommended Articles

This article compares U.S. and Chinese approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) exports in Africa and examines how these disparate approaches have produced both downstream benefits and challenges for the region.

On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly unanimously adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, an international treaty designed to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and…

As the Trump administration proposes a sweeping overhaul of the US foreign assistance architecture by dismantling USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and restructuring the State Department, there is an…