Title: Nuclear Nonproliferation After the Russia-Ukraine War

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, accompanied by nuclear threats to deter intervention by NATO states, is unlikely to spark a broad wave of nuclear proliferation. However, growing concerns among political leaders in Japan and South Korea about nuclear coercion by China and North Korea, and questions about the durability of U.S. defense commitments, is driving interest in nuclear acquisition. To stanch this interest, the United States may be pressured to share nuclear weapons with these allies, while Russia could look to deploy nuclear weapons on the territories of its allies.

A popular but ahistorical narrative is emerging about Russia’s war on Ukraine: if only Kyiv had retained the Soviet nuclear weapons stationed on its territory at the end of the Cold War, it could have deterred Vladimir Putin’s nuclear-backed annexation of Crimea in 2014 and attempted occupation of the rest of Ukraine today. This narrative ignores the fact that those weapons were controlled by Russia and Ukrainian leaders at the time did not want to be treated as an international pariah for attempting to become a nuclear-armed state. Rather than focus on a flawed counterfactual that emphasizes the importance of nuclear power, the world would be much better off asking how Russia’s actions could affect nuclear nonproliferation. In the context of perceived growing risks of inter-state conflict and a re-ordering of the international system, it is plausible that one or more countries worried about suffering a similar fate as Ukraine decide to seek nuclear weapons, or that Russia and the United States opt to violate international nonproliferation rules by sharing nuclear weapons with allies.

The impact Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has on nonproliferation will depend considerably on the outcome of the conflict and how states perceive the resulting lessons. If Russia defeats Ukraine and occupies, dismembers, or otherwise destroys its sovereignty, Putin’s use of nuclear threats to deter outside intervention may motivate other states facing perceived existential threats to seek the security of their own nuclear deterrence capability. Or, even if Ukraine survives as a sovereign entity, states may perceive that nuclear weapons could better deter aggression from nuclear-armed adversaries.

Alternatively, other potential coercers (China and North Korea) may observe the collective response to Russia’s invasion and be less inclined to attempt similar aggressive military action. In that case, the apt lesson may be that a strong and resilient conventional military capability, backed by the justness of defending one’s own territory and the support of the international community (including extended nuclear deterrence in the case of U.S. allies), is sufficient to deter aggression by a nuclear-armed adversary.

Even as the outcome of the conflict remains uncertain, growing concerns about the threat of nuclear-backed aggression–especially among U.S. allies–indicate significant challenges ahead for the nonproliferation regime.

A Referendum on U.S. Security Guarantees

Nearly all of the dozen or so countries that face perceived existential nuclear coercive threats today also possess nuclear weapons or are protected by alliances with nuclear-armed states. Of these, the countries most concerned about an invasion by a nuclear-armed neighbor are the Baltic states, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Notably, all of these states are security allies or partners of the United States.

To NATO states, South Korea, and Japan, the United States “extends” nuclear deterrence as part of its security guarantees, meaning Washington promises its willingness to use nuclear weapons in conflict if needed to defend these allies. (Only Taiwan does not enjoy a formal alliance that conveys such protections.) Whether the leaders and publics of these countries perceive a need for an independent nuclear weapon capability is largely a function of belief that the United States (and others in the case of NATO) will follow through on defense commitments, including by risking nuclear damage to its homeland during a conflict.

Contrary to fears that the U.S. and NATO members states will not follow through on their commitments, the U.S. and Europe have taken many punitive actions against Russia for its aggression in Ukraine. For example, there have been coordinated U.S. and European targeted economic sanctions on Russian individuals, banks, and companies, supply of advanced conventional weapons to Ukraine, and forward deployment of military forces to NATO’s eastern flank. These actions constitute strong demonstration of a joint commitment to “defend every inch” of NATO territory, including the Baltic states.

NATO has among its members three states with nuclear weapons, and the United States deploys nuclear weapons in Europe. (These nuclear weapons are shared in the sense that the United States retains ownership and control of these weapons, but if NATO decided to use them the weapons would be delivered by aircraft owned and piloted by individuals from the NATO states on whose territories they are deployed.) NATO’s nuclear strategy is characterized by a strong emphasis on collective nuclear deterrence, thus attenuating the main drivers of nuclear proliferation among NATO members.

Proliferation Pressures Concentrate in Asia

Japan and South Korea, in contrast, are more singularly reliant on commitments from the United States for their security. The U.S. “nuclear umbrella” over its East Asian allies does not comprise nuclear sharing agreements analogous to NATO or forward deployed nuclear weapons (apart from nuclear-armed submarines patrolling in the Pacific). Both Tokyo and Seoul have strong and improving conventional military capabilities, yet there are clear concerns in both capitals about American resolve to sustain the alliances in the face of nuclear threats from adversaries, concerns which were exacerbated by former President Donald Trump’s apparent disdain for alliances.

Accordingly, some prominent Japanese and South Korean political figures argue for bolstering existing extended nuclear deterrence arrangements–calls that have grown louder after the Russian invasion. On February 27, 2022, for example, former Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo argued that Japan should debate a nuclear sharing arrangement like NATO. In South Korea, numerous conservative politicians call for U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons with nuclear sharing arrangements; these proposals also appeared in conversative party political platforms in recent elections. These arguments are occasionally accompanied by threats that, if the United States does not meet these demands, South Korea and Japan would have no choice but to develop their own nuclear weapons. These statements have domestic political purposes and are not merely about intra-alliance bargaining, but are still notable.

Unlike nearly all non-nuclear NATO allies and Taiwan, Japan and South Korea have the capability to construct nuclear weapons in the near future. Proliferation is a hypothetical option that leaders in Tokyo and Seoul could exercise depending on their interpretation of the lessons of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Thus, how the United States responds to requests to augment nuclear deterrence in its security alliances in Asia is the most important determinant of future proliferation.

The Rise of Nuclear Sharing?

There is another, potentially broader consequence of Russia’s actions: the possibility that the United States or Russia decides to share nuclear weapons with their allies.

The United States is often accused of double standards by making exceptions to international nonproliferation rules for its friends–such as negotiating a nuclear cooperation agreement with India in 2005 or agreeing to provide Australia with a nuclear-powered submarine in 2021. In this regard, opting to develop nuclear sharing arrangements with Japan and South Korea may be seen as a pragmatic option that prevents or delays a decision by those states to acquire their own weapons. The United States would undoubtedly argue that such a move would not constitute proliferation as such, since it would maintain ownership and control of the weapons. Yet the legality would be contested, given that the United States, as a member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), is committed not to transfer nuclear weapons or control over them to states that do not have nuclear weapons. U.S. nuclear sharing arrangements with NATO pre-date the NPT and are therefore widely understood as a singular exception. Nonetheless, the willingness to ignore or selectively exempt allies from universal nonproliferation norms has been a feature of U.S. policy.

But the United States may not be the only one that decides to share or otherwise equip its allies with nuclear weapons. Russia’s actions in Ukraine indicate changing views in Moscow about the extent to which the current international order serves Russian interests. Indeed, with its invasion Russia eviscerated the security assurances it provided to Ukraine when the latter agreed in 1994 to return the Soviet nuclear weapons stationed on its territory. Such so-called negative security assurances by states with nuclear weapons to states without them are a pillar of the nonproliferation system. Russian leaders seem intent on undermining a system they believe favors the United States, which may require jettisoning rules perceived as inconvenient restraints.

Depending on the outcome of its invasion, might Russia assess benefit from breaking its nonproliferation commitments? Until recently it would have been unimaginable that Russian leaders might consider this option. Unlike the United States, Russia does not extend nuclear deterrence to its allies and partners. But in a world order post-invasion of Ukraine it seems plausible Russia might offer nuclear sharing or other nuclear inducements to states it seeks to recruit to its orbit. Already, Russia appears to be moving to re-station nuclear weapons in Belarus in violation of agreements put in place at the end of the Cold War. It does not seem far-fetched that Russia might make similar offers to some of its prospective clients in the Middle East. Indeed, Russia may justify such actions on the grounds that the United States shares nuclear weapons with its European allies and may soon with its Asian ones.

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine may broadly foretell a trend in the international system towards clashes between states seeking to maintain the existing order and those aiming to subvert it. One way the United States might seek to maintain the current order and prevent further proliferation is to create nuclear sharing arrangements with South Korea and Japan. Ironically, one way that Russia might seek to tear down the existing order is to share nuclear weapons with its prospective allies to broaden a coalition aligned against the West.

Neither outcome is assured, fortunately. The United States can seek to bolster deterrence in Asia in ways that do not require nuclear sharing. When the time comes to re-establish dialogue with Moscow on nuclear matters (which should be a priority regardless of the outcome in Ukraine), Washington should look for ways to sustain Russian cooperation on nonproliferation, including on cases such as Iran. Succeeding in both policies will be tricky and, in the latter instance, perhaps distasteful. But the security benefits of continued efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons are far greater than the increased risk of nuclear armed conflict if nonproliferation efforts fail.

…

Toby Dalton is senior fellow and co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His research spans nuclear nonproliferation and energy issues, justice and the global nuclear order, and nuclear challenges in East and South Asia.

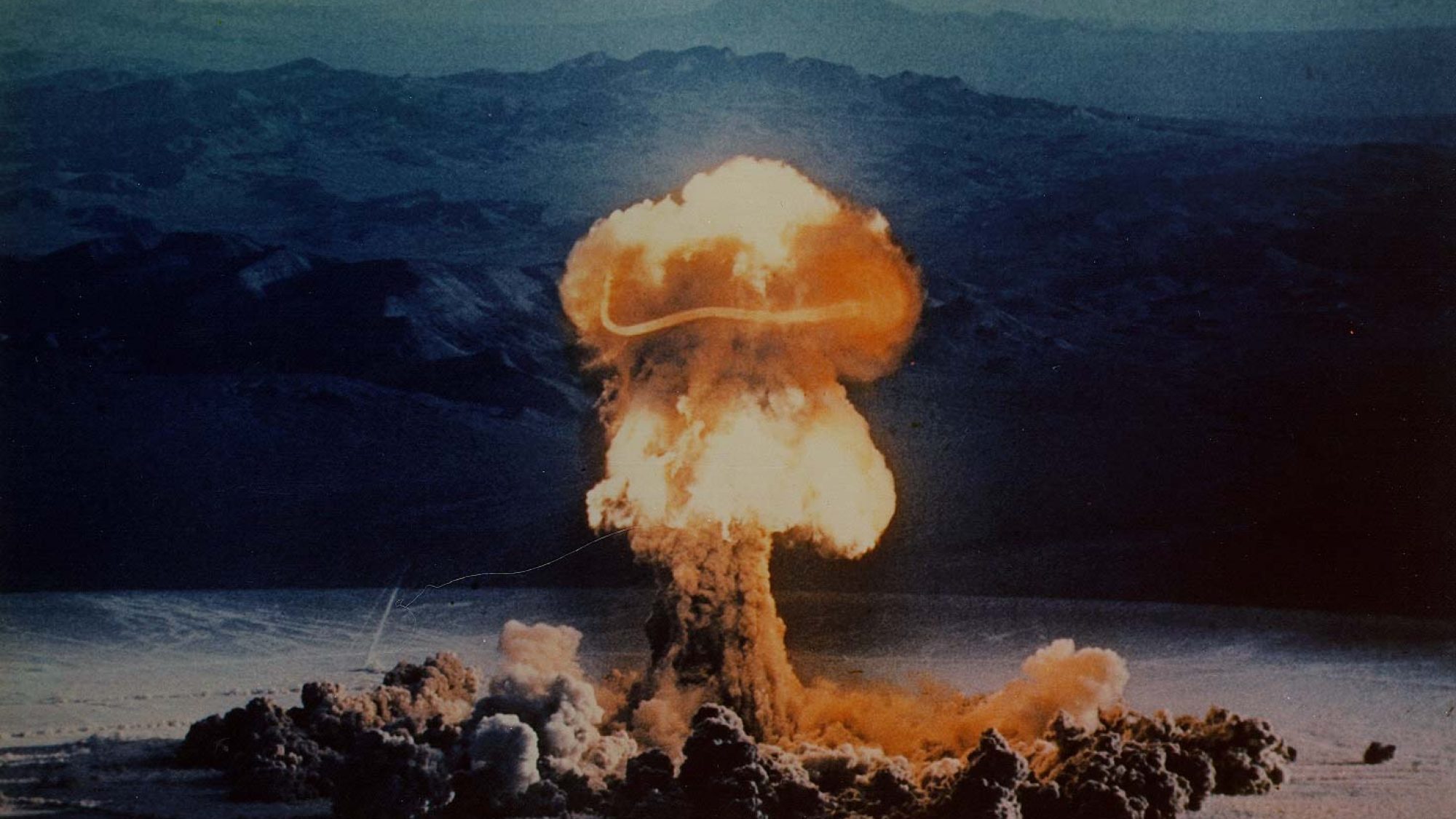

Image Credit: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

More News

This paper examines the interrelated crises facing the Maghreb region: water scarcity and gender inequality. It describes the current approach towards addressing water scarcity and how incorporating women’s voices into…

This article compares U.S. and Chinese approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) exports in Africa and examines how these disparate approaches have produced both downstream benefits and challenges for the region.

On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly unanimously adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, an international treaty designed to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and…