Title: Masspersonal Social Engineering and the Emergence of Individualized Information Warfare

Russia’s 2016 election interference operation challenged dominant assumptions about the nature of cyber conflict. That operation and others like it mark the emergence of what the authors call “masspersonal social engineering.” This essay argues that the combination of masspersonal social engineering with capabilities for individualized and personalized warfare developed during the war on terrorism point to the potential for masspersonal information warfare in future conflicts.

Russia’s use of cyber-enabled information operations to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election marked the return of great power competition and conflict after a decade and a half of U.S. focus on counterinsurgency (COIN) and counterterrorism (CT). This shift raised two important questions. First, by defying longstanding assumptions about how cyber warfare would be used (i.e. not the long-anticipated “cyber Pearl Harbor”), it brought into question the relationship between cyber and information operations, which had largely been seen as separate concerns to that point. Second, it raised the question of which, if any, of the lessons learned and capabilities developed during more than a decade of COIN/CT operations might remain relevant in a future of great power competition.

This essay draws from the authors’ recent work on the emergence of masspersonal social engineering to argue that the events of 2016, combined with the emergence of information technology-driven kill/capture operations during the U.S. war on terrorism, point to the potential emergence of masspersonal information warfare. Masspersonal information warfare merges cyber and information operations with principles of individualized warfare to deliver manipulative messages in an increasingly targeted manner and at scale. The essay first defines the practices of masspersonal social engineering. It then describes the features of individualized and personalized warfare and offers examples that point to the potential convergence of these two sets of practices into masspersonal information warfare.

Masspersonal Social Engineering

In the wake of the 2016 election, U.S. Cyber Command acknowledged that more work was needed to explore the relationship between cyber and information operations. The authors have addressed this challenge by exploring the histories of both computer hacking and propaganda to place the events of 2016 and its aftermath into a wider historical context. The concept of “social engineering” has been important to both fields and shares a number of common practices, including trashing, pretexting, bullshitting, and penetrating.

Trashing refers to the practice of gathering data on one’s target, whether that is an individual, organization, or entire population. Both hackers and propagandists engage in trashing, which often involves making use of discarded or forgotten data (such as from old email addresses, social media posts, or other sources).

This data is used to create pretexts for engagement, from a hacker playing the role of a repair person needing building access, to a colleague sending an expected attachment, to the propagandist creating a tool such as a front organization or collection of social media bot accounts.

After setting the pretext, social engineers engage in bullshitting. Bullshitting goes beyond mere lies or fake news, but is rather a clever combination of accurate information, deception, and friendliness meant to win over the target.

These social engineering tactics penetrate minds, machines, and media discourse, shaping targets’ perceptions and actions in ways that benefit the social engineer but is often not in the targets’ best interest.

Traditionally, the study of communication is divided between interpersonal communication (e.g. face-to-face or one-on-one) and mass communication (e.g. one-to-many and impersonal). Hacker social engineering represents a form of manipulative interpersonal communication, while traditional propaganda represents a form of manipulative mass communication. However, the internet and social media have blurred the distinction between the two, leading to the emergence of what communication scholars call “masspersonal communication.” From this perspective, 2016 marks the emergence of a form of social engineering that the authors dub masspersonal social engineering (MPSE). MPSE is a form of manipulative communication that combines the individualized and personalized targeting of hacker social engineering with the desire for mass effects found among propaganda social engineers of the twentieth century. MPSE takes advantage of developments in automation, big data, AI and machine learning, and behavioral advertising, but also harnesses individual hacks and low-tech armies of trolls interacting with others—one-on-one and en masse—in an effort to sway the perceptions and actions of audiences both large and small.

Individualized Warfare

How then might MPSE translate into situations of open conflict among states? The answer can be found in one of the capabilities developed during the U.S. war on terrorism. While some may lament that most of the lessons learned and capabilities developed to fight that war will be irrelevant amid great power competition, there is one set of capabilities that may also be important to the realm of cyber and information conflict: the individualization and personalization of kill/capture counterterrorism missions. Amid the war on terror, the difficulty of being unable to identify the enemy when it is not a traditional army, but often hidden within the wider population, drove a need for those changes in warfare. Identifying the enemy and, among the enemy, pinpointing a high-value target was increasingly viewed as a data collection and analysis problem. Family, biometric, social media, and associational data were collected and compiled into databases to be mined for potential targets. As targets were found, fixed, and finished, additional data was exploited, analyzed, and disseminated to further fuel the cycle of identifying and targeting the enemy.

These kinetic and often lethal efforts made use of existing data collection and analysis tools and techniques from the civilian world, including social media data, biometric collection technologies, and social network analysis platforms. Where information operations are concerned, the use of personalization and individual targeting is already evident in the civilian marketing space, where big data collected from purchasing histories and online activities, AI and machine learning, and micro-targeted advertising are increasingly combined. The use of those tools for manipulative political communication was displayed during the 2016 election in the now-infamous case of Cambridge Analytica. In fact, whistleblower Christopher Wylie went so far as to describe the firm’s actions as a form of “cyber warfare.” While Wylie may be hyperbolic, these trends will likely continue and affect the conduct of information warfare in situations of open conflict in the future. The next section details some examples that point in that direction.

Masspersonal Information Warfare and the War in Ukraine

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war offers some recent examples that indicate a potential future for masspersonal information warfare. During the Euromaidan protests in 2013, Russia individually targeted protestors with intimidating text messages. A 2017 study for the Army Cyber Institute at West Point reported that this tactic was later used against Ukrainian soldiers and their family members. These individuals were not only targeted with messages, but also had their social media posts monitored, their phones hacked, and contact lists stolen, all presumably for the purpose of targeting subsequent information operations. The report predicted that this novel combination of cyber and information operations, which had a demoralizing effect on those targeted, would continue. Indeed, these tactics have returned in Russia’s current invasion, during which Ukrainian soldiers have received text messages telling them to surrender.

But, as in the physical fight, the Ukrainians have performed better in the information battle than anticipated, even making use of the same individualization tactics used by their Russian counterparts. For example, Ukraine has recorded and broadcast the interpersonal communication of captured Russian soldiers calling their mothers, which has been shared and re-shared millions of times on social media. This example illustrates masspersonal communication for information operations. In another case, a Ukrainian newspaper leaked what it claimed was the personal information of roughly 120,000 Russian soldiers, totaling some 6,616 pages of data. Although it is unknown what use, if any, was made of this data, it certainly could have been used for targeted operations against those soldiers or their families if properly exploited and analyzed. In a manner similar to the participation of third-party hacktivists in hacking Russian computer systems, volunteer efforts at masspersonal information operations have benefited Ukraine. In one case, a Norwegian group set up a system that allows anyone to send messages relaying information about the war to hundreds of Russian email addresses at a time. A similar site, created by a group of Polish programmers, allows anyone to send text messages or emails to a collection of 20 million Russian phone numbers or 140 million Russian email addresses collected by the programmers.

Conclusion

These are only a few of the many examples of the increasing individualization and personalization of information operations over the last decade. Certainly, neither information operations nor computer hacking are new phenomena. Instead, what cases like Russia’s 2016 election interference and the operations of firms like Cambridge Analytica point to is the increasingly blurry line between mass and interpersonal forms of social engineering. Just as masspersonal communication has expanded into the realm of social engineering, so too will there be an increasing focus on individualized and personalized targeting. These developments point to a potential future in which an increasingly integrated and fast cycle of trashing, pretexting, bullshitting, and penetrating result in the emergence of masspersonal information warfare.

…

Sean Lawson is an Associate Professor of Communication at the University of Utah and Non-resident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare of Marine Corps University.

Robert W. Gehl is F Jay Taylor Endowed Research Chair of Communication at Louisiana Tech University.

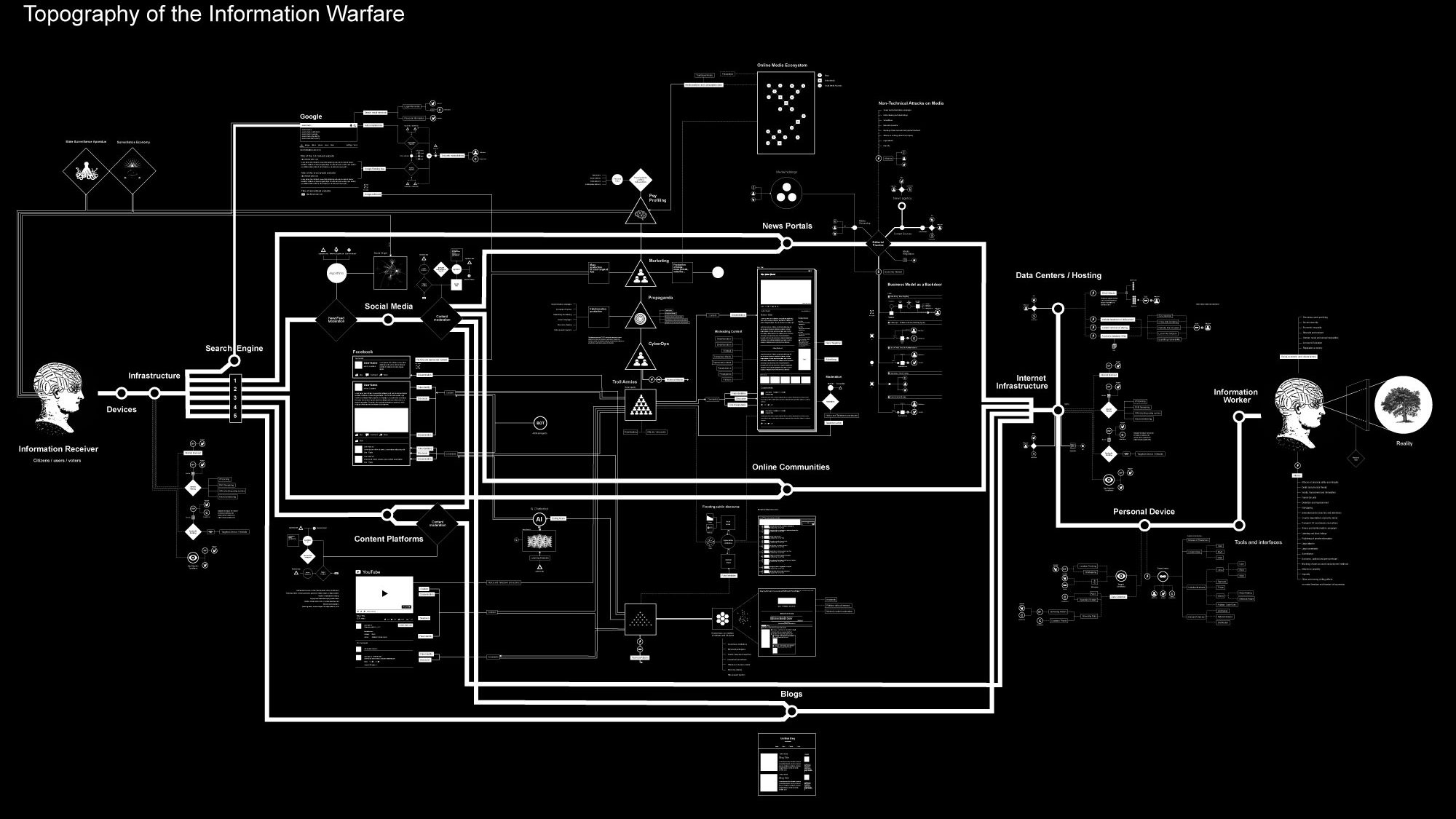

Image Credit: Vladan Joler, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

More News

This article examines the EU’s cyber diplomacy in Moldova’s parliamentary elections from September 28, 2025, which marked a new chapter in the bloc’s cyber diplomacy. Drawing on analysis of Russian…

Export controls on AI components have become central tools in great-power technology competition, though their full potential has yet to be realized. To maintain a competitive position in…

The Trump administration should prioritize biotechnology as a strategic asset for the United States using the military strategy framework of “ends, ways, and means” because biotechnology supports critical national objectives…