Title: The Role of Digital Technology in the Restitution of Cultural Artifacts

Should states and museums use digital technology as a replacement for restitution and repatriation of cultural artifacts such as the Parthenon Sculptures? Technological solutions that help them face up to the injustices of the past are laudable but will not necessarily defuse the repatriation claims they may be bound by. It is unrealistic to expect robots to settle disputes concerning the ownership and belonging of collection items that evoke relationships, knowledge, and sacrifice.

Introduction

A vast corpus of museum collections around the world contain items that were stolen, looted, or smuggled from their original sources and owners. To determine whether a museum is justified in keeping an individual collection item, provenance research may be undertaken to establish several factors such as: the conditions under which an individual object was collected; from and by whom it had been taken in the ownership chain; from where the item had been removed; and how long it had been in that location. This process, however, would be costly and time-consuming if applied to every contentious item. It is therefore worthwhile to consider this issue in a more creative, even “global” manner.

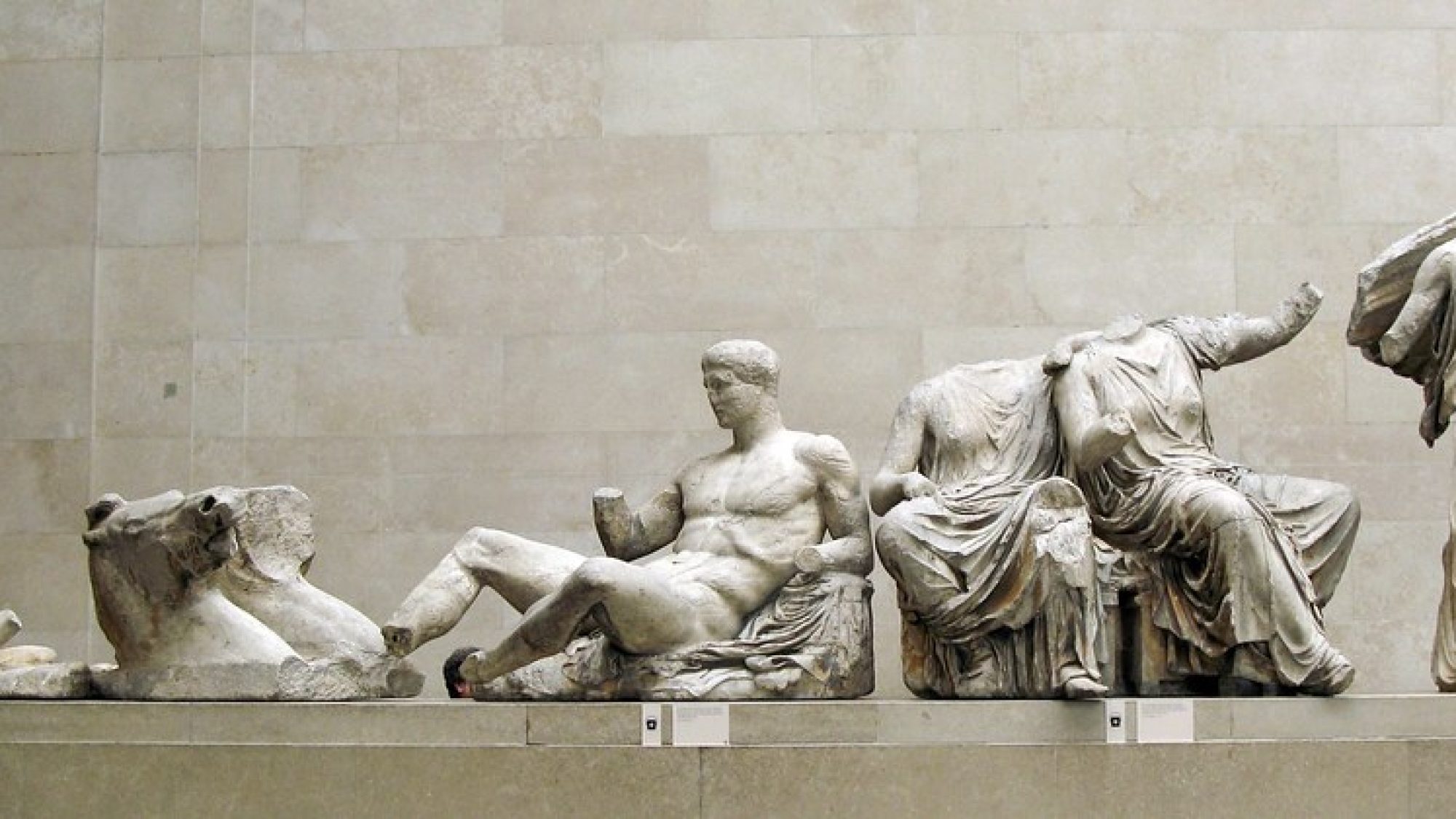

What role can digital technologies play in tackling the issue of stolen cultural heritage and questions about restitution and repatriation? Reports in digital media regularly suggest that virtual reality, 3-D printing, and related technologies could render the physical location of ancient artifacts less important and prompt the imagining of “a new kind of museum.” Ancient sculptures can be recreated in 3-D through LiDAR scanners or even replicated in the same stone as their originals with stone-carving robots. The physical forms of cultural heritage encompass material or corporeal artifacts and even digital artifacts, but the intangible heritage is embodied in people and the generations they give life to. Digital technology could widen public and research access to information about or images of cultural property and heritage that had been removed. For the question of rightful ownership and custody, however, access is not the appropriate determinant. Moreover, digital technology on its own cannot unlock the full meaning of the sacrifice heritage embodies. To explore this ethical dilemma, this article examines the case of the Parthenon Sculptures housed in the British Museum for the past two centuries. In 2020, the Greek culture minister Lina Mendoni declared that the ancient masterpiece’s displacement from Greece was a “blatant act of serial theft … motivated by financial gain.”

Digital reunification is a digitized representation of scattered artifacts and archival records in physically dispersed heritage collections. It reassembles and consolidates the cultural material and associated records that originate from the same location or that share a common provenance. Successful digital restitution provides a way to visualize and study a collection in a comprehensive manner. Pressure has been mounting on the British Museum to permit 3-D scans of the Parthenon Sculptures as a form of digital reunification to return the originals to Greece, where a “robot sculptor” would carve near-perfect replicas of the original set.

The British Museum’s refusal to collaborate with a recent proposal by the Institute of Digital Archaeology (IDA), one of the UK’s top organizations for heritage preservation, came to the attention of the public at the end of March 2022. The IDA announced its intention to seek an injunction to order the British Museum to allow scanning to raise public awareness about the decision-making process concerning access and the making of the scans. It wants to ensure that these decisions are taken even-handedly. The IDA expects the reconstructions based on scans obtained in April 2022 to be high quality even without access to the top and back edges of the stonework.

Stoking Debate

The Parthenon Marbles continue to stoke debate about the return of valuable and sacred cultural property and heritage. They symbolize the essence, aspirations, and sacrifice of the Greeks, as Melina Mercouri declared at the Oxford Union on June 12, 1986. Restitution claims for their return have been forthcoming since 1835, and in 1983 an official claim was made against the UK government.

The dispute has implications for understanding the role of the universal museum in our society and of encyclopaedic museums in the west. The idea of the universal museum was part of the aspiration of the Enlightenment to ensure public access to artistic achievements of the present and the past. These museums exhibit artifacts from a variety of cultures alongside each other for a comprehensive overview that contributes to a cross-cultural interpretation of a set of universal cultural values unconfined by borders. The British Museum has long justified its continued possession of the Parthenon Sculptures with reference to how its stewardship since 1817 has enhanced their intrinsic aesthetic and cultural value. The rhetoric is that they are part of the story which the communities in London and visitors representing all the cultures of the world continue to benefit from. The aim of offering an education to everyone who entered, and of achieving the widest possible access for the public, was considered so important that museums readily deployed plaster casts, copies, engravings, and photographs.

British historian William St Clair famously stoked debate by asking why universal museums seem interested only in originals in his essay on “Imperial Appropriations of the Parthenon.” [i] The “encyclopedic” character of universal museums imposes a burden of greater responsibility on account of their potential to educate and offer new perspectives to visitors. It is highly questionable that the ability of an encyclopedic museum to exhibit the diversity and range could sustain a claim that they account for all cultures of humankind without encountering ethical dilemmas. Divergence in power, memory, and taste in collections will undermine their sweeping propositions. Before any universal museum can claim to have fulfilled its role, the manner in which the objects and collections are sourced and displayed, and how the narratives about their histories are constructed must be transparent.

Critical Heritage Studies scholars frequently challenge the conventional emphasis on tangible expressions of heritage. They draw attention to the value of social practices and processes that other disciplines tend to overlook or undervalue. The true role of heritage is said to lie in constructing identities, developing memories, and ascribing values that deserve to be preserved for the benefit of future generations, rather than preserving the monuments or traditions that have survived from the past. In the new digital world of knowing and being, future generations will grow up with new technologies and new possibilities of seeing. Cultural organizations and states may yet be able to negotiate access to websites and databases, act as hosts, and provide data. Nonetheless, repatriation encompasses tangible heritage as well as intangible heritage embodied in the relationships and knowledge that the material evokes. A more comprehensive definition of restitution or repatriation would encompass the physical return of the material or corporeal cultural heritage that had been wrongfully taken, along with returning control over the intangible dimensions of the material and databases that offer researchers access to information or images about the cultural material in question. The restitution of stolen or looted cultural heritage without returning the intangible heritage related to the material is as incomplete a process as the restitution of intangible heritage without returning the cultural material it relates to.

Resolving Disputes About Cultural Property and Heritage

Provided the provenance and purpose of collections are clear, the educative value of collections does not depend upon the display and storage of original artifacts. Nonetheless, even the strongest proponents of technological solutions must concede that robots cannot chisel away the need for cultural institutions to come to terms with an unsavory past. It is as vital to link objects across collections located in different parts of the world as it is to link collections with archives so that in-depth research could begin or continue. Digital initiatives should be questioned if they do not promote this type of linking or if they undermine efforts to dismantle the physical, geographic, political, monetary, and other barriers to physical restitution. Digital repatriation can be productive when the claimant has no desire to receive back the physical material or when destruction or damage has occurred. One set of replicas of the Parthenon Sculptures in Pentelic marble could reflect the damage wrought by conflict and time, and another could be of the sculptures Phidias created around 447–438 BCE. However, digital repatriation will delay the settlement of disputes if it interferes with the free exchange of the information uncovered in the quest of verifying the provenance information to determine rightful ownership and custodianship. Information Society models lose sight of the rightful ownership/custodianship question if they imply that intangible heritage can be inventoried, removed from the public domain, and then “returned to the exclusive control of its putative creators.”

Conclusion

Confrontations between ontologies of the digital and ontologies of the physical are inescapable in a technological age in which the digital is layered onto the world of things with increasing frequency. When states and cultural institutions rely on digital archives and digital reunification alone, they maintain the status quo of museum collections in the west.

For over two hundred years the display of the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum has paid scant attention to the truth at the heart of the historical discourse. Virtual reunification by means of the display of near-perfect replicas of the Parthenon Sculptures could achieve the aims of the Universal Museum. Virtual reunification cannot achieve the restitution that Greece is seeking. Each carving was made to fit into the Parthenon Frieze at a unique angle and each panel sculpted for a specific place. Even among pieces that appear to have exactly similar proportions, the imperceptible differences are numerous. The sacrifice of the Athenians that grounds the restitution claim is an intangible dimension of the material that is more than the stock of knowledge the Athenians possessed. This explains the ontological priority of the question of their belonging in restitution claims for cultural heritage, as well as the urgency of responding to the real question of our time: “Can digital technology help cultural institutions and states to face up to the injustices of the past and the repatriation claims they may be bound up in?”

. . .

Dr Christa Roodt is Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Glasgow. She has published widely in the field of international cultural heritage law. Her current research interrogates the structure of law and ethics argument in the restitution and repatriation of sacred cultural heritage removed during the colonial era.

[i] William St. Clair, “Imperial Appropriations of the Parthenon,” in Imperialism, Art and Restitution, edited by John Henry Merryman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 65-97.

Image Credit: Flickr; Justin Norris; Creative Commons License 2.0

Recommended Articles

This article examines the EU’s cyber diplomacy in Moldova’s parliamentary elections from September 28, 2025, which marked a new chapter in the bloc’s cyber diplomacy. Drawing on analysis of Russian…

Export controls on AI components have become central tools in great-power technology competition, though their full potential has yet to be realized. To maintain a competitive position in…

The Trump administration should prioritize biotechnology as a strategic asset for the United States using the military strategy framework of “ends, ways, and means” because biotechnology supports critical national objectives…