Title: Could Compulsory Turnout Turn Out Something Fresh For Northern Ireland?

The democratic institutions created for Northern Ireland with the Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement in 1998 have not functioned for some 40 percent of the ensuing twenty-five years. This is, in part, because the legislature and executive are dominated by two hardline parties of opposing views, despite the majority of voters in Northern Ireland possessing more moderate views. Consideration should be given to changing the means by which members of the Northern Ireland Assembly are elected. Compulsory turnout could be one such avenue to ensure the electoral makeup of the Assembly better reflects the composition of society in Northern Ireland twenty-five years after the Agreement.

Introduction

The definition of insanity, so it is said, is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Northern Ireland’s democratic dysfunction exemplifies this idiom.

The Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive have functioned for only 60 percent of the time following their establishment in the 1998 Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement; they have been suspended for two-thirds of the past seven years. This precarious situation partly arises from a consociational arrangement in Northern Ireland involving mandatory power sharing between the two predominant political communities—unionist and nationalist—which makes it possible for the largest parties in each political community to effectively exercise a veto over the legislature and executive. This mechanism is used as a form of leverage: a refusal to govern until the party’s particular concerns are addressed, usually through governmental intervention. Despite the disruption and dysfunction that arise from this unusual political system, there is currently no concrete plan to change it.

In the absence of functioning Northern Ireland institutions, the Parliament of the United Kingdom has passed emergency legislation to allow basic governance in the region. According to its most recent iteration, if there is still no Northern Ireland Executive by January 18, 2024, another election must be held before a new legislature can be formed. Few, however, would realistically expect another election to result in an outcome that meaningfully shifts the political balance, no matter how lively the campaign. This is of particular concern for a region where paramilitary groups are still active, and where political parties’ commitment to “exclusively democratic and peaceful means of resolving differences on political issues” is posited (by the 1998 Agreement) directly against the “use or threat of force… for any political purpose.”

Bringing the Wider Electoral Pool to the Polls

One way of bypassing cyclical political stagnation could be the introduction of some form of compulsion in legislative elections. Approximately one-sixth of all the states in the modern world that hold elections do so under a compulsory voting regime. The UK Electoral Commission defines compulsory voting as “a system of laws mandating that enfranchised citizens turn out to vote.” There is wide variation in how such laws are codified and enforced (1), making it difficult to generalize the impact of compulsory voting on voter engagement, government spending, and policies (2). Such diversity helps explain why the empirical impact of compulsory voting does not seem very impressive even when examining turnout itself: the average voter turnout in countries with compulsory voting is only about 7.3% higher than in those where voting is voluntary.

The main argument in favor of compulsory voting is a subsequent increase in voter engagement, particularly among poorer and younger and less-educated citizens, which in turn bolsters the perceived democratic legitimacy of elected bodies. However, compulsory voting does not allow for the fact that the political system itself may be seen as illegitimate. In this sense, any act of voting in a system perceived as illegitimate may be seen as tacit approval for the status quo. This may be a valid concern for Northern Ireland, whose consociational model of power-sharing has been perceived as reinforcing unionist/nationalist divides that are increasingly irrelevant to the social and political values and attitudes in Northern Ireland society.

One way around this criticism is to orient electoral policy towards compelling ‘turnout’ rather than ‘voting’ per se. There is a subtle but important difference between the mandatory casting of a valid ballot (‘compulsory voting’) and mandatory attendance at a polling station or subscription for a postal ballot (‘compulsory turnout’). If turnout—rather than voting—is mandatory, people will be more likely to vote but less likely to cast a ballot on a purely random basis. If those who would have been non-voters by habit or inclination are compelled to show up at the polls, it is the responsibility of those seeking elected office to convince them to take the next step and cast the vote. In this way, as scholar Dean Machin writes, mandatory turnout can give “political parties greater reason to address non-voters’ interests and preferences” and thereby “broaden a polity’s democratic base.”

What Difference Might Such a Change Make?

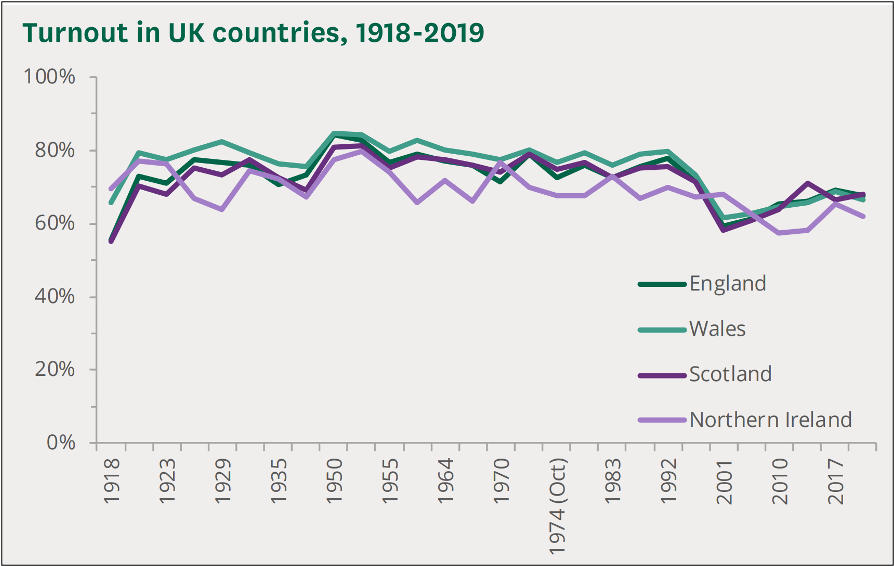

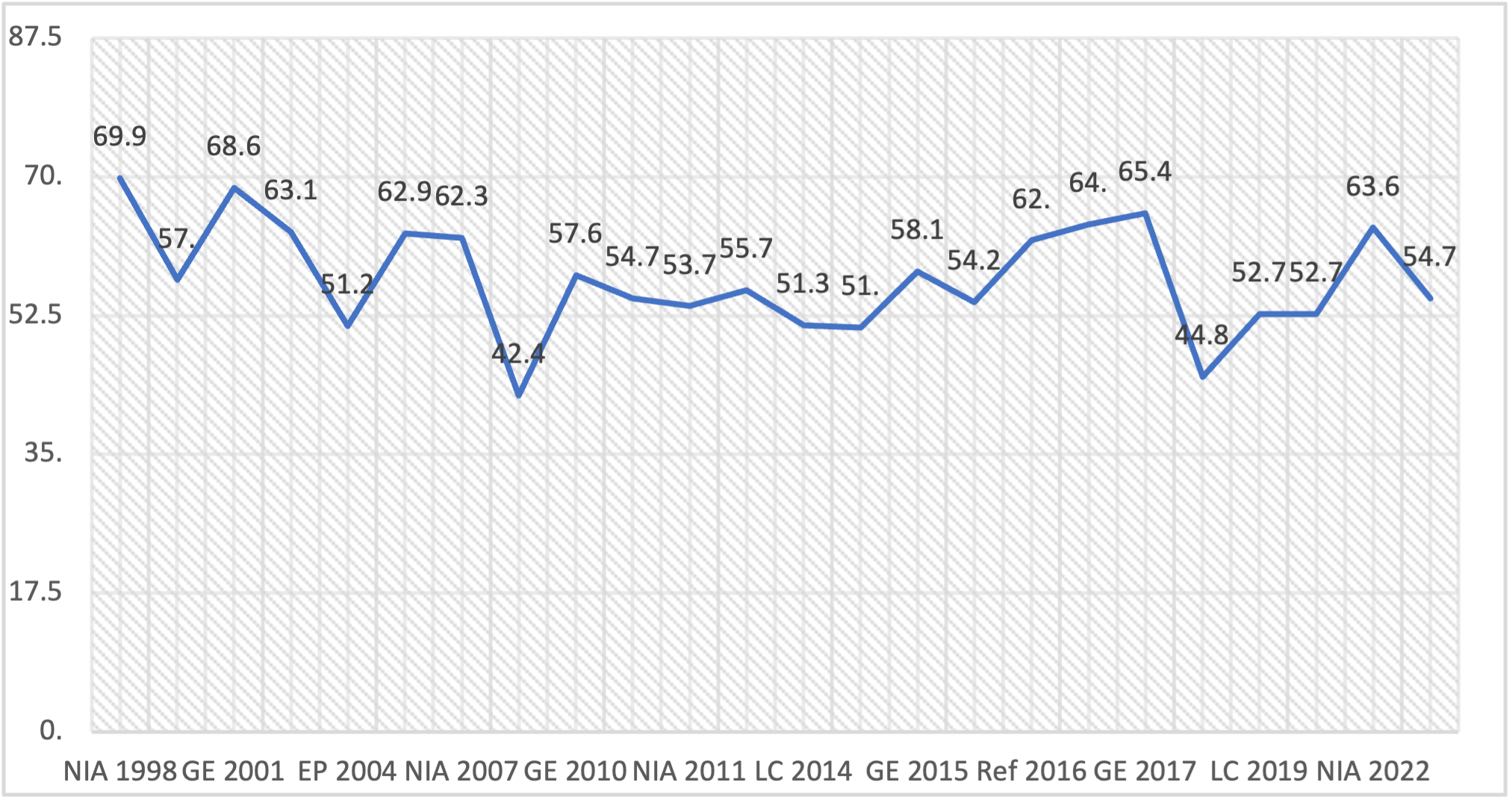

Arguments for and against compulsion in the electoral process should focus on the particular characteristics of each political system concerned. Voter registration is already mandatory in Northern Ireland and voter turnout is not particularly low compared to the rest of the UK (Figure 1), with an average of 57.2% turnout since the Agreement, including in referendums and European Parliament elections (Figure 2). However, turnout has been well below fifty percent in some areas, including in working-class unionist communities where paramilitary groups exert some control. The most significant variable when it comes to non-voting, however, is age. Northern Ireland Election Studies indicate that non-voters tend to be younger (around half of those under 30 do not vote) and to hold more socially progressive views.

Figure 1: Turnout in General Elections in the UK, 1918-2019 (Source: House of Commons Library, 2023)

Figure 2: Turnout in NI elections and referendums since 1998. Note that there are different electoral systems at play, with General Elections being First Past the Post and the others using the Single Transferable Vote system (NIA is Northern Ireland Assembly elections; EP is European Parliament elections; GE is UK General Election; Ref is Referendum; LC is Local Council elections)

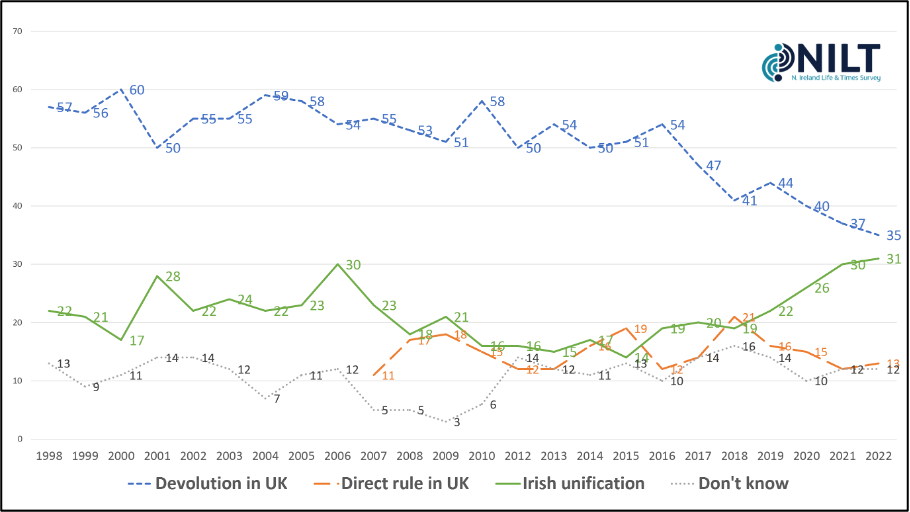

As such, we might expect compulsory turnout to result in a change in the active electorate (3) and parties will have to adapt to attract the votes of younger, more liberal citizens whose political thinking is not set in terms of unionism or nationalism. This may bode well for parties ‘non-aligned’ along the traditional unionist/nationalist binary – but, as noted above, that would depend on their ability to persuade those new to the polling stations to cast a valid vote (4). For instance, the growth in Catholic registrations on the electoral register since 1998 has not translated into a surge in support for pro-Irish unity parties; the majority of people in Northern Ireland continue to support having their own regional democratic institutions, with power devolved from Westminster.

However, support appears to be waning the longer those institutions are mothballed (Figure 3), which does offer a sign of hope.

Figure 3: ‘What do you think should be the long-term policy for Northern Ireland?’ (NI Life & Times survey, 1998-2022).

As things stand, voter disillusionment in Northern Ireland facilitates party complacency; instead, it should be a challenge that every party feels compelled to address. In the current system, there is little incentive for parties to reach out beyond their traditional electoral bases. Compulsory turnout could challenge assumptions about the relative size and habits of these traditional constituencies and might offer new ones. It would be a significant change, albeit insufficient on its own: compulsory turnout cannot guarantee the effectiveness of institutions, nor restore public confidence in them. But it would offer a touch of creative unpredictability in Northern Ireland’s democratic process. Amid a downward spiral of political deadlock, perhaps that is what has been missing the most.

(1) Article 37 of Argentina’s Constitution states that “suffrage is universal, equal, secret, and mandatory” whereas Australia’s compulsory voting laws are not formally in the constitution, but are enforced via federal law. Further variation can be found in who is required to turn out. In some countries, voters who reach a certain age (70 years old in Luxembourg and Peru) are no longer required to vote. In Brazil, voting is compulsory once an individual turns 18, but voluntary for 16-17 year olds. There are variations of enforcement too, with penalties ranging from the non-existent (Honduras) to the non-enforced (Greece), to the light ($5 fine in Singapore), to the heavy (‘civil rights’ are to be removed from non-voters in Ecuador).

(2) After a run of elections with low voter turnout, the UK Parliament flirted with the idea about a decade ago. The House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee conducted an inquiry on the subject, but failed to come to a conclusion on the effectiveness of compulsory voting. Support for the idea in the UK has fallen since (from 55% in 2015 to 45% in 2022), with Labour voters being more in favour than Conservative ones.

(3) The lack of change in the views/choice of the average voter seems to be the reason why compulsory voting in Austria did not appear to lead to policy changes.

(4) Change in the demographics of an active electorate can result in a change in the legislature. The October 2023 Polish general election saw its highest ever turnout (74.4 percent), with a particular surge among female voters and voters under 30 (up by 12 and 22 percentage points respectively, compared to the 2019 election ) and resulted in a pushback against right-wing populism.

…

Katy Hayward MRIA FAcSS is Professor of Political Sociology in Queen’s University Belfast, where she is also co-Director of the Centre for International Borders Research and a Fellow of the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice. Her most recent books are Northern Ireland a Generation after Good Friday (2021) and The Irish Border (2021). She wishes to acknowledge the research assistance of Dr James Greer and Dr Matthew O’Neill.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Recommended Articles

Africa accounts for approximately two percent of global air travel. Given the continent’s vast size and large distances between major trade hubs, enhancing intra-African air connectivity will be…

An estimated 7.9 million Venezuelans migrated abroad for the long term under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule as Venezuela’s political, economic, and social crises have deepened. Alongside rising Venezuelan migration, migrants…

Amid stalled U.S. federal climate engagement and intensifying transatlantic climate risks, subnational diplomacy has emerged as a resilient avenue for cooperation. This article proposes a Transatlantic Subnational Resilience Framework (TSRF)…