Title: Multicultural Policies in Malaysia: Challenges, Successes, and the Future

Since Malaysian independence in 1957, the Malaysian government has sought to manage its diverse ethnic groups. The Malaysian government has historically given preferential treatment to Malay people through the New Economic Policy, creating imbalances in Malaysian society. This paper considers this policy, explores its repercussions, and provides policy suggestions for resolving entrenched discriminatory practices with more equitable reforms.

Introduction

Malaysia is a multi-ethnic society of 32.4 million people, comprised of 69.4 percent Bumiputera (ethnic Malay and other indigenous groups, notably from Sabah and Sarawak), 23.2 percent Chinese, 6.7 percent Indian (these two ethnic groups collectively known as non-Bumiputera or non-Malay) and 0.7 percent “Other.” Malaysia’s multicultural policies have historically given preferential treatment to Malay people through the New Economic Policy, creating imbalances in Malaysian society. This paper considers this policy, explores its repercussions, and provides policy suggestions for resolving entrenched discriminatory practices with more equitable reforms.

These policies trace back to the colonial “divide and rule” policies, through which the British organized society based on “essentialized ethnic categories.” The British divided labor by ethnicity with the Malay in the unwaged peasant sector and the non-Malay in the waged capitalist sector. The groups were also geographically split, with a rural-urban divide. As such, the communities were highly segregated, engendering both unequal economic status and separate cultures. After gaining independence, though the government sought to rectify such injustices through the New Economic Policy (NEP), it has only inflamed divisions between Malay and non-Malay. As such, the new regime under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim seeks to reverse the legacy of the NEP. To do so effectively, Ibrahim must implement revisions incrementally to avoid political backlash, judge progress qualitatively, and include more non-Malay in the government.

The History of Ethnic Divisions in Malaysia

During their colonial rule, the Portuguese in 1511 and the Dutch in 1641 did not interfere with the local culture or structure of Malaysian society. Their aim was mainly the monopoly of trade. In 1726, however, the British, spurred by the need to consolidate raw materials for industrial capitalism at home, enabled unrestricted and large-scale immigration of Chinese laborers for work in the tin mines and later Indians for rubber estate cultivation. The Chinese, who predominated in the major commercial centers, were allowed to operate local trade in the villages and participate in a network of small shops and dealerships. The British, however, maintained the Malays within their traditional lifestyle. Hence, the British created two distinct and parallel methods of production: large-scale production and commercial activities of the British and Chinese versus the traditional methods of peasant agriculture and fishing practiced by the rural Malays. In the process, British colonialism subjected most Malays to limited economic and educational achievement, contributing to the later ethnicization of poverty.

By 1957, the British granted independence to Malaysia but first set up a power-sharing arrangement among the Malay, Chinese, and Indians. The Malay would possess political supremacy, while the non-Malay, specifically the Chinese, would remain economically dominant. The Malay recognized non-Malay rights to citizenship but maintained the power to determine non-Malay quotas in civil service, public scholarship, tertiary education, and trade and business licenses.

Post-Independence Challenges

After independence, Malaysia continued to struggle with structural inequalities between the Malay and non-Malay, leading to the eruption of inter-ethnic violence in 1969. This violence spurred the creation of the New Economic Policy (NEP), a series of affirmative action programs that favored the Malay in politics, civil service, business, higher education, language, religion, and culture. The ruling Alliance Party, composed of three parties representing the Chinese, Malay, and Indians, argued that affirmative action was needed to correct structural inequalities and lessen the sense of “relative deprivation” among the Malay, as the Chinese retained economic preeminence in Malaysian society. The dual goals of the NEP were to eradicate poverty and eliminate the conflation of the Malay race with economic disadvantage.

While the NEP sought to reduce poverty and restructure society, its implementation was problematic. Through political patronage facilitated by weak political institutions, Malay elites manipulated NEP policies for their political and economic gain, intensifying intra-ethnic inequities and deepening ethnic divisions. Improving Malay social and economic standing came at the expense of need-based poverty reduction. For example, since the 1970s, Bumiputera contractors have been favored by businesses, as political actors often award contracts and hence have obstructed fair competition. Despite favoring Malay people, the NEP never adequately developed their competencies. As a result, the Malay political elite were reluctant to phase out the NEP.”

Anwar Ibrahim and SCRIPT

The sharp rise of ethnocentric initiatives from Malaysian political leaders in the last decade, coupled with the economic and political instability engendered by COVID-19, led to the 2020 government. The 2018 election of PH marked the end of authoritarian rule, which had lasted for six decades. However, free elections were short-lived, as race-based rhetoric and political maneuvering by the Muslim-Malay nationalists caused the PH government to collapse after only two years of its five-year term. Nationalists tapped into Malay resentments over ethnic displacement, stoked antireform resistance, and called for the protection of Islam.

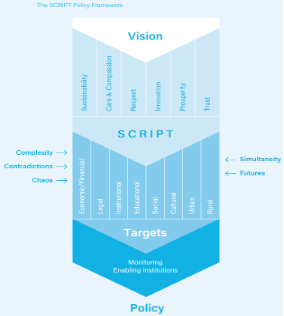

In November of 2022, the Malaysian King appointed the widely popular Anwar Ibrahim as Prime Minister with a coalition government of ethnically diverse parties. Contending with a fractured nation, in July 2023, Ibrahim enacted a new policy framework, Malaysia Madani, to build a sustainable, caring and compassionate, respectful, innovative, and prosperous Malaysia based on mutual trust (SCRIPT) between the government and its people. Figure 1 illustrates the SCRIPT framework.

Figure 1: The SCRIPT Policy Framework

SCRIPT intends to eliminate the NEP’s ethnicity and race-based social restructuring and focus instead on need-based programs. For instance, SCRIPT seeks to make the bidding process among contractors more transparent and avoid unfair preferences for Malay contractors. SCRIPT appears to address the ethnic tensions fueled by the NEP’s political manipulation, but its implementation remains a challenge. For example, within this policy framework, it is unclear whether or how pro-Bumiputera policies, such as the quota in public university enrolment, public sector employment, and public procurement, will be adapted. Even in the latest Madani economy, the essence of the NEP is still strong. As such, achieving equitable representations and ensuring SCRIPT’s success remain a challenge for Ibrahim.

Implementing SCRIPT

Since the beginning of his premiership, Ibrahim’s efforts have been complicated by internal stumbling blocks within his own party and roadblocks from the opposition. Though the influence of the NEP’s deeply-entrenched policies cannot be resolved immediately, SCRIPT can strengthen inter-ethnic relations if implemented in the following ways:

First, SCRIPT must cautiously adopt equitable representation, participation, and human capital development without employing quotas for various ethnicities. In both the public and private sectors, SCRIPT should implement practices that boost need-based representation. In higher education, for instance, rather than setting quotas on student intake based on ethnicity, as the NEP did, tertiary institutions could specifically incorporate need-based selection opportunities for economically disadvantaged individuals. While this is slowly taking place, Ibrahim understands that he cannot abolish the quota system immediately. Suddenly lifting the quota system and replacing it with a need-based system would be political suicide, as the Malays made up the largest single ethnic group in the country at 57.9 percent.

Second, SCRIPT should address the issue of unequal representation of ethnic groups in civil service, which has long been dominated by a Malay professional and administrative class. Currently, mostly Malay control the public sector, and non-Malay control the private sector. The public sector typically offers better work than the private sector in terms of work hours, leave, termination, and lay-off benefits. SCRIPT, however, has not addressed this issue. Policy dialogues in SCRIPT should start by clarifying the underlying principles and practical scope for promoting diversity in civil service–acknowledging that all ethnic groups should be represented. SCRIPT can also highlight and praise past efforts as well as current practices to increase diversity.

Currency, many non-Malay prefer private-sector employment to the public sector due to its better pay. The civil service should emphasize that it offers more autonomy and a more supportive work environment to draw in non-Malay talent. Ibrahim’s government, as the first of a multi-ethnic coalition, could steer policy discourses and seek new grounds for fostering diversity. Doing so will take time, but SCRIPT can start by including policies on this issue of representation and diversity early on.

Finally, the new administration should not solely use quantitative measures to assess the outcomes of affirmative action reform. Previously, the success of NEP policies has been measured quantitatively. For example, the NEP set 30 percent Bumiputera equity ownership as a central target (from the 2.4 percent measured in 1970). Such quantitative measurements, however, failed to assess more subjective capabilities such as participation, competitiveness, and self-reliance of the Bumiputera. SCRIPT policies have not yet addressed this limitation. Capability development through quality education, vocational training, experiential learning, mentoring, and coaching would likely reduce polarization between ethnic groups. Thus, SCRIPT policies should focus on achieving strong qualitative outcomes.

Conclusion

The NEP was created to empower the economically disadvantaged Malay ethnic group but has since been abused by Malay leadership. In introducing the Madani concept, from which SCRIPT policies originate, Ibrahim and his coalition government aim to radically rework the structure of Malaysian society by repealing NEP policies. This will be an uphill battle, as doing so remains politically contentious.

Though they have not been rigorously discussed in the government, SCRIPT policies have been embraced by grassroots organizations. A recent survey shows that Anwar Ibrahim is endorsed by all ethnic groups as the most suited to be Prime Minister. SCRIPT and Anwar Ibrahim appear to be gaining popularity with dissenting voices waning.

Ibrahim’s success will likely depend upon whether the political elite respects the interests of the Malaysian people. In its current form, SCRIPT reflects the political will of some elites, like Anwar Ibrahim, to move away from the destructive legacies of his predecessors. However, it remains to be seen whether this approach will garner widespread political support and yield lasting rewards.

…

Noraini M. Noor is a professor at the Department of Psychology, Ibn Haldun University, Turkey, prior to which she was with the International Islamic University Malaysia. A social/health psychologist by training, her areas of research include women’s work and family roles, work‐family conflict, work stress, race relations, religion, and peacebuilding. Currently, she is researching the Islamic tradition’s perspective on the nature of Man and how this differs from what is commonly understood in modern psychology.

Image Credit: Pexels