Title: Concurrent Challenges of Conflict and Climate Change in Myanmar

The relationship between climate change and violent conflict is complicated. Existing studies suggest that climate change increases armed conflict through indirect pathways, including detriment to livelihoods, displacement, migration, and existing conflict dynamics. The exact nature of this interaction depends on each country’s political, socio-economic, and military contexts. Violent conflict, however, increases vulnerability to climate change by aggravating societal vulnerability and making populations more vulnerable to weather shocks. This suggests a plausible feedback loop of violence and vulnerability, worsened by climate change. Myanmar provides an illustration of the concurrent challenges of climate change and violence exacerbating societal vulnerability with potentially consequential security outcomes.

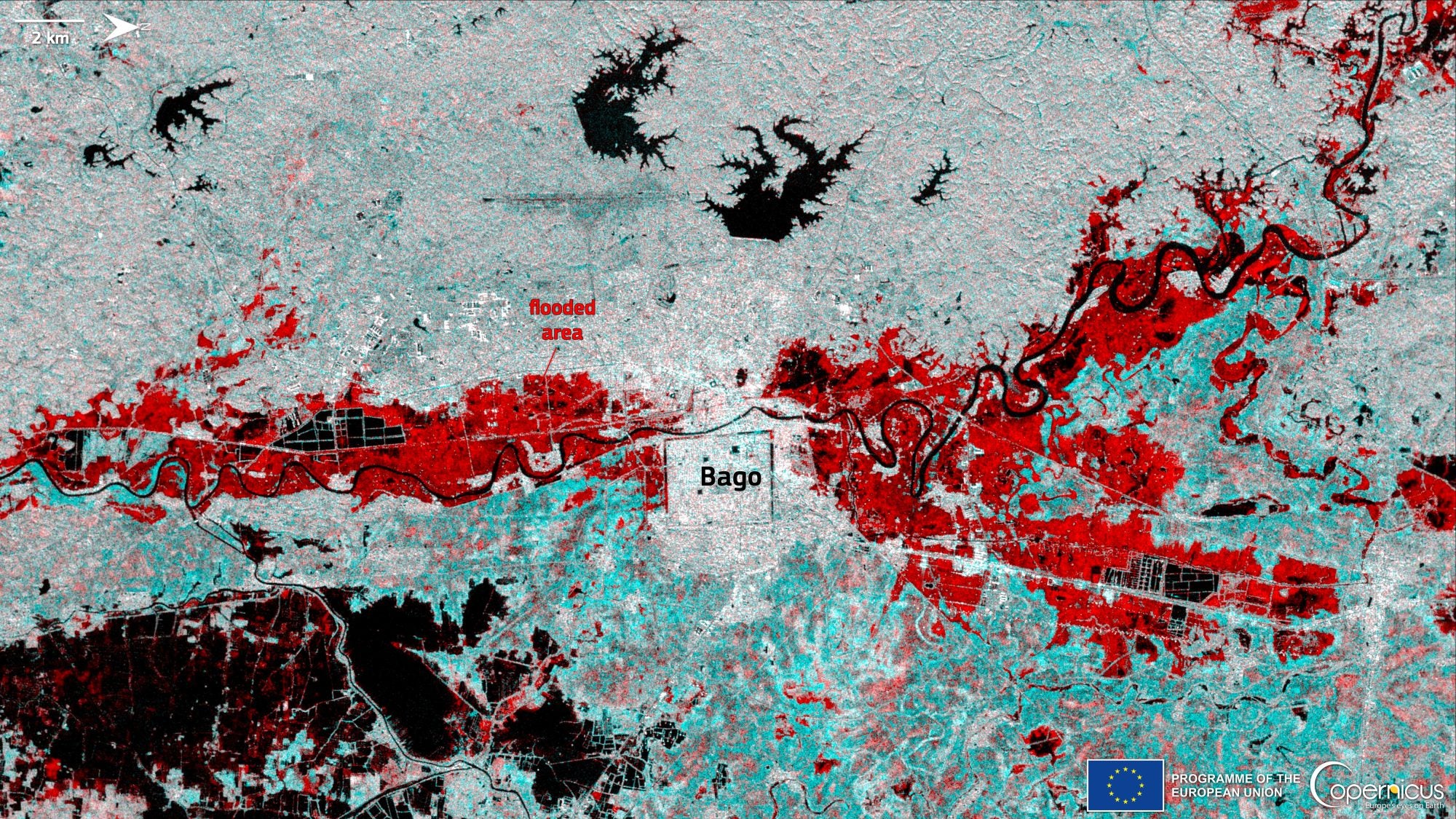

Myanmar’s Climate Exposure and Escalating Conflict

Myanmar is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. It faces a high risk of climate hazards such as floods, cyclones, extreme heat, and landslides. Myanmar’s vulnerable coasts are particularly exposed, threatening the more than 5 million people living in low-lying and coastal regions. Furthermore, Myanmar’s predominantly rural populations, relying on climate-vulnerable agriculture, fisheries, and forestry sectors for their livelihoods, are ill-prepared for an increasingly worsening climate. Environmental degradation, on the whole, increases vulnerability. For instance, practices such as illegal logging have worsened the risk of landslides during flooding, which annually occurs during the rainy season.

To add to these humanitarian challenges, Myanmar’s civil war is the world’s longest ongoing conflict. The military’s direct rule for nearly a half-century (1962-2011) plunged the country into isolation from the international community and exacerbated its extreme underdevelopment. Following a decade of liberalization, the military coup in 2021 pushed the war to a new height with new frontlines in even previously peaceful regions such as Magway and Sagaing. Violence escalated to an unprecedented level and extent when numerous local militias formed anti-coup resistance forces.

The 2021 military coup abruptly ended a decade of political and economic liberalization. During the 2010s, the country’s prospects looked hopeful as it entered a liberal reform period through a paced mode of transition, in which the country held two general elections that most international observers viewed as free and fair and made significant progress in discussing the country’s federal and democratic future. However, the democratic strides during the reform period had major flaws which led to the rise of violence and hatred against religious and ethnic minorities that resulted in the Rohingya genocide. Despite its flaws, the civilian-led government made some progress towards federal democracy and peacebuilding. The 2021 coup and subsequent conflict escalation have had devastating impacts on this progress. The military coup not only overruled the election outcome but also diminished the gains in institutional and policy building in national and regional governments, including policies for climate action and disaster risk management.

Violent suppression by the State Administration Council (SAC), a new name for the military regime, has galvanized pro-democracy groups into a broad-based anti-junta alliance including ethnic minorities. Many youth activists formed People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) to resist the junta by arming themselves, first as self-defense that later turned into militia groups against the military and its auxiliary forces. The National Unity Government, an exile government formed by elected parliamentarians, has supported the PDF formation as a security strategy against the military regime. These PDFs also fight alongside more established Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), such as the Kachin Independence Organization and Karen National Union.

The military coup and subsequent conflict have devastating humanitarian consequences. Prior to the coup, around 1 million people needed humanitarian aid. Now, more than 18 million individuals, roughly a third of the population, are in dire need of humanitarian assistance, with 3 million displaced within Myanmar. Additionally, 1 million Rohingya refugees are living in camps in Bangladesh, while thousands, including women and children, are undertaking perilous sea journeys in search of safety and a dignified life in Indonesia and Malaysia.

These two crises interact in Myanmar in a mutually reinforcing manner. The conflict frustrates environmental efforts and climate change exacerbates the conflict by increasing instability.

Climate Risks on Multiple Scales: Implications for Insecurity

The systemic risk of climate change to Myanmar’s population contributes to local, national, and regional vulnerabilities. The interconnected nature of this vulnerability can generate social and political outcomes with broader implications for both national and regional security.

Local

With declining livelihood and economic opportunities, exacerbated by the conflict, Myanmar’s rural populations turn to environmentally disruptive livelihoods as a coping mechanism. This problem is particularly pronounced in the southern coastal Tanintharyi Region, known for its high-quality charcoal from mangroves, where poor villagers turn from their traditional farming and fishing practices to charcoal production, leading to deforestation. Due to the unstable electricity supply since the coup, the demand for charcoal for household cooking has increased, accelerating deforestation. Since mangroves provide a natural barrier against storm surges during increasingly intensifying cyclones, this deforestation further harms Myanmar’s climate resilience. For example, the loss of mangrove forests contributed to the devastating loss of life and damage during Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

At the local level, climate change disrupts communities and marginalized groups, and cumulative and protracted marginalization can exacerbate existing grievances linked to conflict. Access to land is particularly an important factor in adaptive capacity for populations exposed to climate change, and insecure land tenure disproportionately affects ethnic minority groups relying on customary land and forests for alternative food sources. These local dynamics, in turn, perpetuate larger grievances against the military, and particularly among ethnic minorities who experienced decades of violence and displacement during civil war.

Climate change, in combination with conflict, also leads to greater human insecurity of the poor and the marginalized. Poor harvests due to droughts and flooding cause farmers to become indebted. Unless micro-finance can be provided by communal arrangements, poor families are charged up to 10% per month in interest rate by landowners. This climate burden disproportionally impacts women, ethnic, and religious minorities, calling for an intersectional approach to further our understanding of the human security implications of climate change.

National and sub-national

When extreme weather events have a nationwide impact, inadequate state responses can cause a political crisis, threatening state integrity. The previous military regime’s response to Cyclone Nargis in 2008, which claimed the lives of more than 130,000 people, was marked by complete incompetence. The regime’s only strategy was to restrict access and communication to the disaster-stricken Irrawaddy delta, in an attempt to deflect criticism. The cyclone precipitated the further deterioration of the junta’s political authority domestically and internationally. France urged the international community to invoke the ‘responsibility to protect’ in the UN Security Council to authorize the aid delivery to the cyclone-affected region. While unsuccessful, this attempt challenged the international legitimacy of the junta and shaped foreign policies toward the country. Furthermore, the military regime overruled domestic and international concerns about the scheduled constitutional referendum just 8 days after the cyclone’s landfall. The referendum was declared successful, and the regime announced the promulgation of the 2008 Constitution based on the reference. The opposition contested the regime’s claim of 90% turnout and reported widespread incidents of voter intimidation and fraud.

More recently, the SAC militarized responses to Cyclone Mocha in 2023 aggravated conflict dynamics in Rakhine State. The SAC restricted immediate access by the UN and international NGOs to the disaster-affected areas in Rakhine State. In the absence of international aid, the Arakan Army, a powerful rebel group, stepped up its efforts in humanitarian aid delivery with the help of local civil society actors. This effort entailed evacuating more than 100,000 people, providing relief, and supporting reconstruction and recovery. The stateless Rohingya, deprived of freedom of movement, were disproportionately affected by the cyclone, clearly illustrating the dire consequence of political marginalization in the context of climate change. While the SAC’s aid restriction may have been intended to weaken the civilian support of the Arakan Army, the regime’s militarized response backfired, heightening local grievances against the regime and boosting support from the rebels.

In addition to the rapid onset of climate disasters, Myanmar faces a tremendous need for climate adaptation for social and ecological resilience. The conflict has disrupted environmental and climate initiatives in the country, undermining the progress made during Myanmar’s “political opening era,” including work on climate change adaptation and reforms on natural resource governance. International funding for climate resilience and environmental management was cut off during the coup and not resumed. Additionally, since the coup, logging and mining activities have increased, including the exploitation of lucrative jade, rare earth minerals, timber, and gold. These unregulated, widespread resource extraction activities have led to environmental destruction, pollution, and land degradation, increasing people’s vulnerability to climate hazards.

Regional

At last, some climate-related security risks extend beyond national borders, potentially impacting the security of neighboring regions. Migration from Myanmar to neighboring countries is primarily driven by political and economic factors, worsened by climate change. Declining livelihood conditions and worsened economic situations since the coup have led young people in Myanmar seeking opportunities to emigrate. The adverse climate impact on agriculture, a vital source of livelihood, serves as a significant driver of economic migration for rural youths looking for employment in neighboring countries. Thailand currently hosts some 2.5 million migrant workers with permits from Myanmar, a number expected to rise. Some of these migrants hold legal documents, however many lack official permissions. A growing number of online and call scam centers along Myanmar’s border regions present a greater security risk with a rampant human trafficking and illicit trade crisis, as Khaled Khiari, Assistant Secretary-General for Middle East, Asia and the Pacific, Departments of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs and Peace Operations argues. As climate risks change migration patterns, these problems could grow into a regional issue, posing a risk of destabilizing the fragile borders.

Recommendations

Since the coup, Myanmar has faced concurrent challenges of climate change and armed conflict, with local, national, and potentially regional security implications. Resolving these challenges requires coordinated and persistent efforts at all levels.

Local civil society and community actors, who serve as frontline responders to day-to-day obstacles, play a crucial role in building climate resilience on the ground. Their importance lies in their knowledge of ecological, socio-economic, and intra-community dynamics at the local level and their potential for community mobilization for resilience building. Installation of micro-hydropower facilities in war-torn Chin State is an example of such efforts to expand renewable energy by local communities. Such effort also helps with combating deforestation as villagers can access electric cooking stoves instead of relying on charcoal. Supporting these local actors is crucial for any international and regional actors aiming to bolster climate resilience in Myanmar.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) should also have a significant role in reducing climate-related security risks and support climate resilience building in this crisis-stricken country through regional cooperation. While ASEAN’s engagement with Myanmar has been challenging, the role of the ASEAN-appointed envoy could be critically impactful. If the envoy can lead the international community in strategically engaging with the junta with coordinated sanctions and other international mechanisms, they may be able to influence the regime’s behaviors. At the same time, ASEAN envoys can constructively engage with resistance groups and facilitate support for local communities in non-government-controlled territories through practical and innovative channels. The leadership of ASEAN is much needed to immediately cease attacks on civilians and to ensure safe passage for humanitarian assistance amid climate-related disasters. Failing to do so could have lasting impacts on the affected Myanmar people and their future, as well as regional stability in Southeast Asia.

. . .

Kyungmee Kim (PhD) is a researcher at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University and a Senior Associate Researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s Climate Change and Risk Program. Her current research focuses on the intersection of climate change and insecurity, examining how climate resilience building can mitigate the risk of conflict and fragility.

Image Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2023, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended Articles

Critical maritime infrastructures (CMI), and in particular undersea communication cables, are increasingly under threat of attacks by malign actors who benefit from asymmetric capabilities and jurisdictional complexities in the maritime…

This article explores how the Palestinian crisis and the death of the two-state solution endangers the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. It illuminates the complicated relationship between Jordan, Israel, and Palestine…

This article explores the uncertain future of Arctic governance amid shifting global geopolitics. It argues that whether Washington and Moscow opt for confrontation or cooperation, multilateralism in the Arctic…