Title: Understanding 1960s Japanese Intermedia with Dr. Miki Kaneda

Art and music serve as a shared language among all humanity. Yet historically, they have often been easily categorized into different genres or styles with little discourse on the intersection of media, especially on a transnational scale. To understand intermedia as a bridge across various types of media, particularly within the context of Japanese-US relations during the pivotal 1960s, GJIA sits down with Dr. Miki Kaneda.

GJIA: In your piece “The Unexpected Collectives: Intermedia Art in Postwar Japan,” you discuss Japanese intermedia, particularly the art exhibited at the Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan, in 1970. Can you briefly describe intermedia and its distinct characteristics, along with other experimental or avant-garde practices seen in Japan in the mid-twentieth century?

MK: Intermedia was first used by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in the 19th century, later adopted by American artist Dick Higgins to describe artworks that did not fit into any single media category. There is a lot of performance–it’s experimental. The form of intermedia that I am interested in emerged in the 1960s in New York City. Japanese artists in New York at that time caught wind of this idea and brought it back to Japan, where it gained traction in the late 1960s. It was really short-lived, but I think it was a pivotal idea, not just for its cross-media status as an art form but also for how it changes the way we might think about what art is, what being experimental is, who makes it, and where it belongs.

GJIA: One key focus of your research is studying the transnational networks that have helped frame interpretations of 1960s Japanese experimental music. In your work, you challenge the narrative that Japanese avant-garde practices are merely “borrowed” or “derivative” of Western aesthetics in the post-World War II context. How do you believe the relationship between Japanese avant-garde music and other music movements around the world of the time should be viewed, and how can academics and the wider public resist falling to these outdated hegemonic narratives?

MK: In a sense, yes, intermedia art is borrowed and derivative, but under what frameworks is being derivative considered bad? This is the framework of the Western avant-garde, bringing us shock, novelty, and radical departure. What’s interesting to me about intermedia and the intermedia artists working in Japan is how they challenge us to rethink these systems from the beginning–systems of structure, language, and the very assessment of art itself.

It’s great and exciting to see a lot of movement towards diversity and inclusivity in the art and music world, but we can’t just stop at inclusion. The current challenge is that now we have included Japan as part of the narrative, it becomes almost a stand-in for the Western avant-garde–I see regularly that aspects and values dismissed once as modernist or heteronormative have been given a pass in the context of the Japanese avant-garde. The idea that “because it is not from Europe or America, we are being inclusive” reinforces existing values. I think that is the challenge we need to grapple with.

GJIA: How have you observed the legacy of 1960s Japanese avant-garde music and questions about the intersection of race, gender, and national identity play out in our world today, whether in contemporary art movements or beyond the art world?

MK: There has been enduring interest in 1960s Japanese avant-garde in the last couple decades. Major US museums have shows featuring Yoko Ono’s Japanese Fluxus, and at New York’s Japan Society, there is an exhibition curated by Midori Yoshimoto about Fluxus women. It is exciting to see the spotlight on women artists. In the 1960s, many active women who often got sidelined.

On the other hand, we cannot just rest on this as completed progress, and it’s essential not to uncritically celebrate these developments as revolutionary. Even within the Japanese avant-garde, there exists complicity with American discourse on race or gender. For example, many are familiar with the transformation of Black avant-garde or avant-garde jazz in the ’60s, but these narratives are often siloed under labeled trajectories like “the history of jazz” or “the history of the avant-garde.” Intermedia attempts to bring these threads together, but the lack of a cohesive framework for understanding the influence of jazz on experimental music poses a challenge. There exists a great intersection between race, gender, and nation within the Japanese avant-garde that was deemed radical, but when you look at the influence of jazz, there lacks a framework and language to talk about this. There is still room to develop that conversation.

How does this play out in our world today? I wouldn’t say the situation is a result of the direct influence or impact of Japanese intermedia or experimental music. I see resonance in contemporary artists, particularly black, indigenous, and other artists of color who are trying not just to be part of the art world or musical canon but to reshape the narratives by creating new language and naming things that were unheard of, invisible, and excluded by the historical narrative.

GJIA: Music is an important aspect of culture, which has historically served as a tool of political soft power for countries in the domestic and international realm. How do you view the potential benefits of countries better understanding and promoting avant-garde music movements on the domestic and international stage?

MK: There are two key moments for intermedia in terms of prominent cultural events. The first is the “Cross Talk Intermedia Festival” supported by the United States. In the Cold War, Japan was a strategic location for the United States, so the notion was that the people interested in this event would be urban cosmopolitan college students and educated people who were in positions to shape the future diplomatic discourse. By endorsing this festival, the United States sought to project its values of free speech, democracy, and experimental ethos. Underlying this event was an implicit expectation of “cooperation” from the Japanese people and companies–really a soft “coercion”–particularly under the shadow of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. The Japanese artists hence saw this event as an artistic opportunity to critique the system from within, creating space for critical reflection on US-Japan relations and the global power dynamics. Many musicians and composers in this event adopted the aesthetic of noise, symbolizing a direct against this diplomatic project and the national agenda for “cooperation,” as noise disrupts communication and subverts established narratives. At the same time, because it is noise, that message of critique is also potentially falling apart. For example, “Voices Coming” (1969) by Joji Yuasa demonstrates moments of conversation filled with expressions like “you know,” “oh,” and “hmm”–communication that has no content or message, only hesitation and ambivalence. That crystallizes some of the issues that composers were grappling with by using noise as an aesthetic.

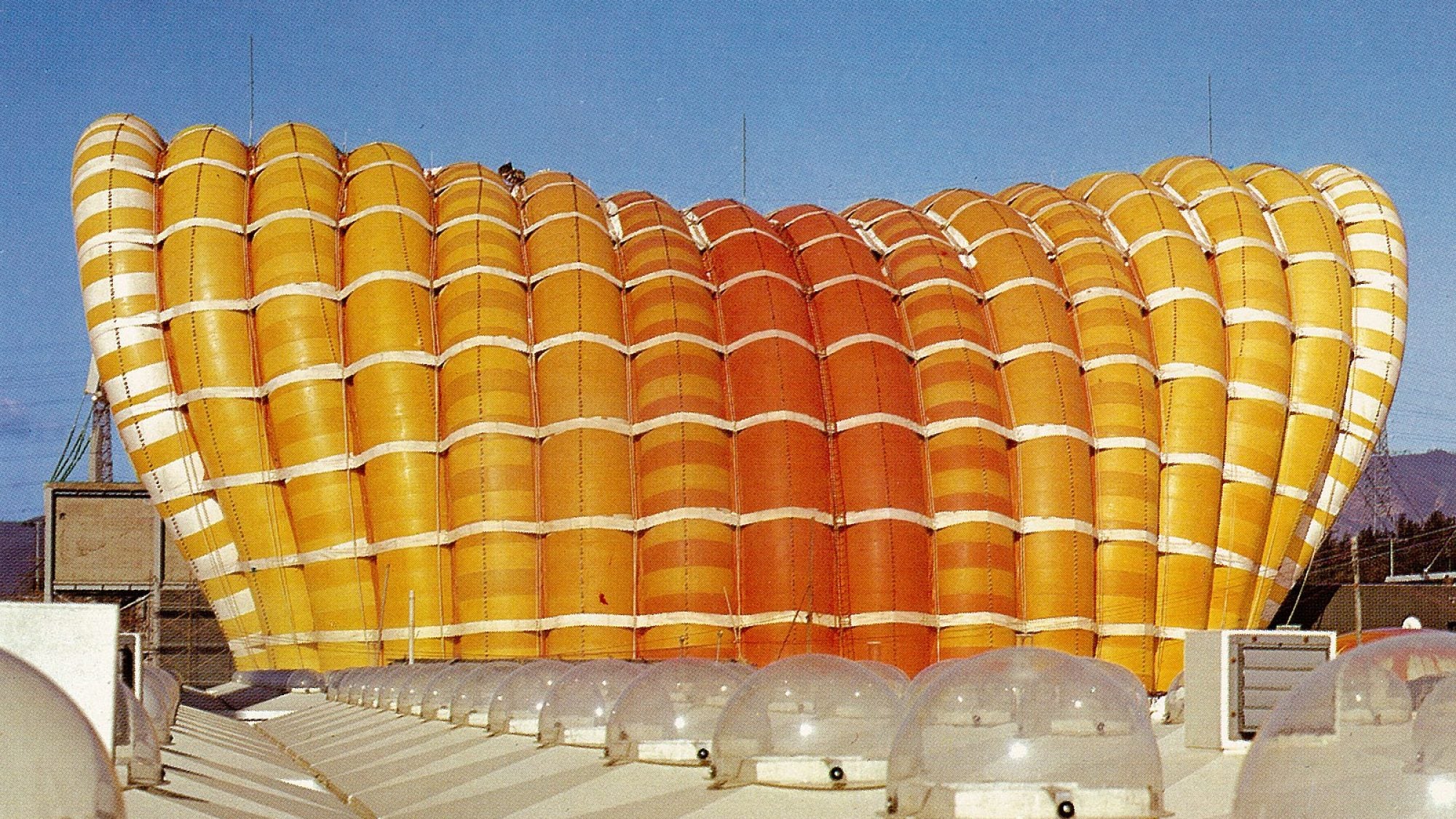

Expo ‘70 was the other key moment in intermediate art. It was international, but its largest audience was domestic. Again, we have a similar case where these experimental artists were invited by the government to put on spectacles. The visual landscape of Expo was psychedelic and colorful. While the Japanese government was trying to get young people excited about being Japanese and being part of this technological and economic growth, if you look carefully, these constructions were unfinished and weird.

There are many layers to Expo. For some, the final outcome is that the noise just all falls apart–this is the end of the avant-garde movement in Japan because it is complicit with the government’s agenda. On the other hand, some of the artists who participated were trying to be critical from within. Yet, if you are looking at the other people in the scene, Expo was not just for the artists. Expo was geared towards the young boys who are into Godzilla and collecting things. Expo was like a proto-Pokémon. This world of intermedia might not have worked out for the artists, but it very much took on its own life through anime and collector culture. For me, that is the real success or legacy of Expo. It did not unfold exactly as the government, corporations, or artists envisioned, but it took on a life of its own.

. . .

Dr. Kaneda is an Assistant Professor of Music, Musicology, and Ethnomusicology at Boston University. Her research focuses on transcultural movements and the intersection of race, gender, and empire in experimental, avant-garde, and popular music during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, with a particular focus on Japan and the United States. Previously, she held fellowship positions at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University, Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, and the Museum of Modern Art, where she was a founding co-editor of the web platform post.moma.org. She is currently working on her book project titled “The Unexpected Collectives, Transnational Experiments: Music and Intermedia in 1960s Japan,” which is under contract with the University of Michigan Press.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended Interviews

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

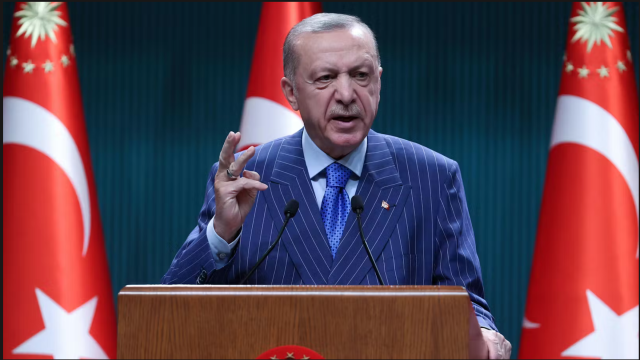

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…