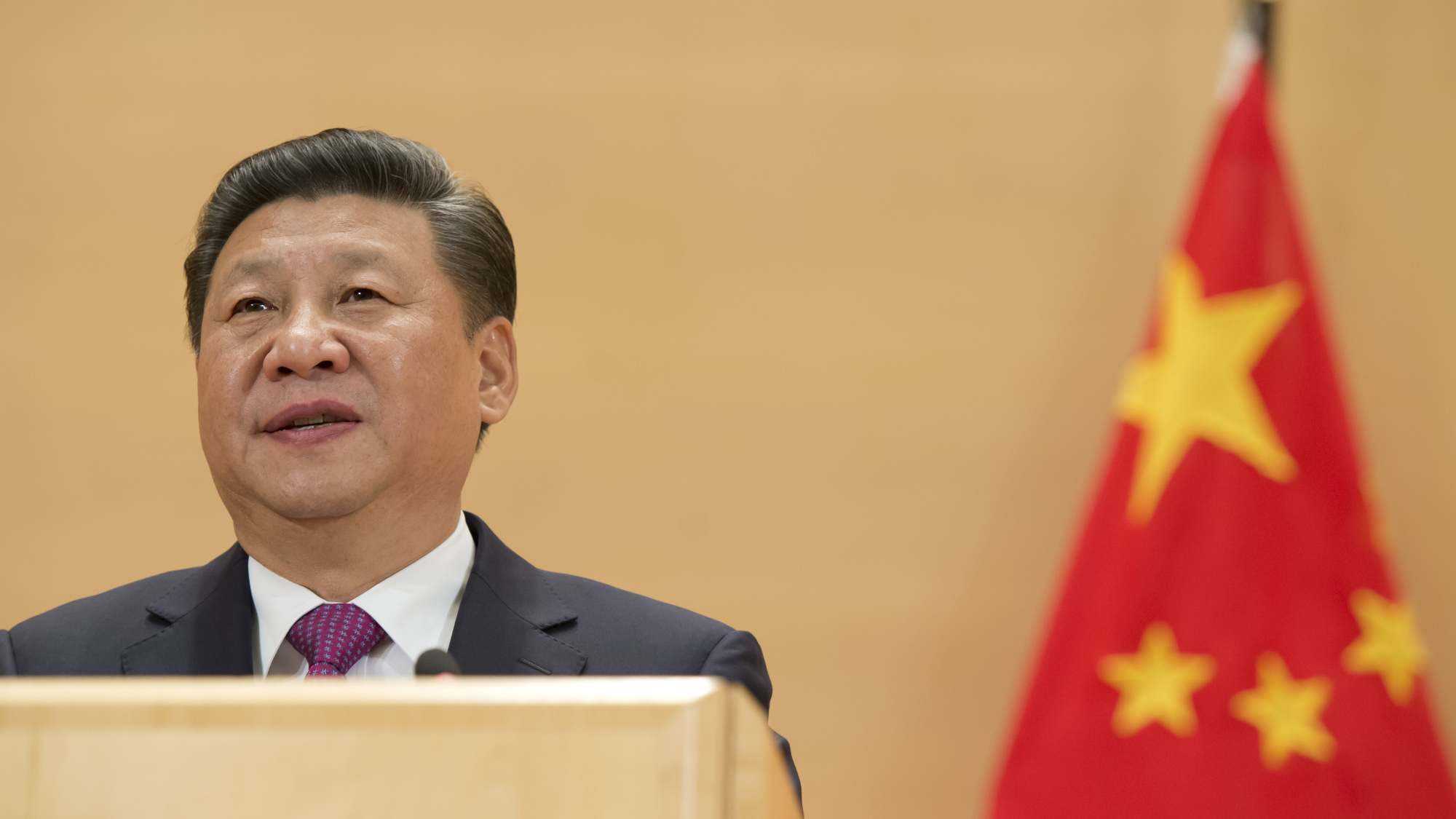

Title: From Deng to Xi, China’s Foreign Policy Identity Has Been Consistent

Despite claims that Xi Jinping’s leadership has adopted a more aggressive foreign policy driven by nationalism, the effect of national identity on Chinese foreign policy has been consistent in the post-Mao era. Instead, China’s perception of its capacity to act internationally is driving a more proactive foreign policy. Therefore, Western states’ China policy should focus on forcing China to question its capacity to act in international affairs by maintaining leadership in areas such as climate change and the war in Ukraine.

Is Nationalism in Chinese Foreign Policy New?

Many US policymakers consider the People’s Republic of China to be the United States’ key strategic rival. As the United States has refocused its attention on China in the past decade, it has found that China has become more aggressive and nationalistic under Xi Jinping’s leadership. To US leadership, China’s coercive “wolf warrior diplomacy” of the late 2010s exemplifies this new attitude. These US policymakers view recent assertive Chinese foreign policy as a departure from earlier post-Mao administrations, which they perceived as pragmatic. Prior Chinese administrations focused on economic engagement rather than ideological objectives and were therefore less threatening. However, contrary to popular belief, the effect of national identity on Chinese foreign policy is consistent and has changed little since the Mao era.

Background

Modern Chinese nationalism is rooted in Han intellectual and popular movements that emerged during the demise of the Qing dynasty in 1911. These movements created a Chinese state identity rather than the flexible identity that subjects of the Chinese empire held. After the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) created socialist patriotism, a form of Chinese nationalism interconnected with a socialist, anti-imperialist nationalism and rooted in China’s experience under Western imperialism during the Century of Humiliation (1839–1949). Then, during the reform era of the 1980s, the CCP adopted positive nationalism, which reduced the anti-Western, anti-imperialist nature of socialist patriotism. For instance, China rejoined the Summer Olympics in 1984 and promoted its success in the games as a Chinese success rather than a victory over Western capitalism. During this era, China sought to rejoin the family of nations.

However, the country soon reverted to socialist patriotism due to international isolation resulting from the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and the CCP’s resultant fears of regime change. This fear led the CCP to introduce patriotic education campaigns in 1994. These campaigns focused on three periods of Chinese history – “five thousand years of splendid Chinese history”, “the humiliation of more than a century,” and “the People’s Republic opens up for progress” – and became the collective narrative of Chinese history and current affairs. Despite possessing a vast, diverse population and a widely contested national identity, these campaigns promoted the national narrative that China is an ancient civilization that has continually resisted Western imperialism and is reclaiming its great power status. China is still far from a totalitarian state – the anti-lockdown street protest of 2022 is a clear example of the fact that the Chinese people are willing and able to push back against their government – but China’s campaigns of the 1990s effectively created one official Chinese historical narrative that reinforces loyalty to the CCP.

Nationalism in Foreign Policy

China articulates its nationalist identity through its foreign policy behavior in areas such as international law and global climate governance. Chinese white papers on Africa policy in 2006 and 2015 framed a narrative of shared victimhood at the hands of Western imperialism, colonization, and unequal treaties. China’s identity as a developing state motivates its foreign policy focus on the Global South and has driven real policy action outside China’s normal policy of non-interference in sovereign states’ internal affairs. For instance, China supported international military intervention during the 2011 Libya crisis, backing a UN resolution that referred Libya to the International Criminal Court on counts of violations of human rights and potential crimes against humanity. China justified its decision by supporting the views of fellow developing states in Africa and the Arab world. Li Baodong, China’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations from 2010 to 2013, stated that China considered “the concerns and views of the Arab and African countries when voting in favor of resolution 1970,” framing China as a sympathizer of countries in the Global South.

China also presents itself as a leader in climate change governance among developing nations. In COP climate summits, for instance, China portrays itself as a significant, responsible stakeholder. It champions the interests of the Global South by supporting positions such as the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR–RC), a principle that acknowledges the unequal distribution of climate action responsibility among countries due to their differing emissions profiles and economic capacities. This underscores China’s commitment to shaping its identity as a leading power on the international stage, where China sets rules that support the position of the Global South rather than accepting those created by the West.

China’s socialist patriotic identity also drives more aggressive foreign policy in territorial disputes and the international economy. China has been assertive in defending its territorial claims, including its “Nine-Dash Line,” which encompasses a significant portion of the South China Sea. Tensions have been rising between China and several states, including Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, over areas such as the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, and Scarborough Shoal. Since China has played a historically dominant role in the South China Sea, it is attempting to achieve a hegemonic role in the region that aligns with its nationalist identity of returning to great power status.

China’s geopolitical nationalistic stance extends beyond its regional neighbors. Epitomized by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambitions manifest in creating Chinese-centric forums for economic cooperation and hubs for financing and logistics across the Global South, including Central Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Rooted in the historical narrative of China’s “five thousand years of splendid history,” the BRI serves as a contemporary testament to China’s enduring position as a critical economic and civilizational center.

From Deng to Xi, China’s Foreign Policy Identity Has Been Consistent: The West Must Change Its Perspective

Many policymakers and media commenters have linked China’s assertive foreign policy to Xi Jinping’s policy of rejuvenating the Chinese nation. However, Chinese foreign policy has been consistent since the early 1990s. During this period, China sought to expand its power in the South China Sea steadily. In the late 1990s, China strived to establish amicable relations with Global South countries and moved toward leadership in global governance. Even the concept of a multipolar world order, evident in deepening Sino-Russian relations and highlighted as a policy change under Xi’s leadership, is rooted in the Chinese foreign policy discourse of the mid-1990s, which debated the extent of China’s development as a great power.

Instead, the key change since the 1990s has been China’s rapid economic growth. While growth has not fundamentally changed China’s identity and institutions, it has strengthened Xi’s ability to achieve the foreign policy objectives of Chinese nationalism. The West expected China’s identity to shift toward liberal, market-led democracy as it integrated with the global economy. This expectation was based on two factors. First, observers reasoned that China’s need for a fully market-led economy to sustain rapid development would require political reforms, including creating an independent judiciary and developing a multiparty political system. Moreover, China’s growing dependence on the international market would force it to support the Western economic order.

However, Western policymakers’ anticipated shift in China’s identity in the 1990s and 2000s did not occur. As the Chinese economy grew, the one-party system expanded to co-opt the newly wealthy and educated elites instead of transitioning to liberal democracy. And while China’s economy improved, China’s foreign policy, identity, and geopolitical ambitions did not change. Thus, China’s increased economic and military capacity supports its emergence as a global power that challenges the model of a unipolar world order dominated by the West.

Despite the development of Xi Jinping thought, the Xi administration has remained consistent with its predecessors in crucial areas of foreign and security policy, including China’s attitude toward Taiwan, which is the last remaining wound from the Century of Humiliation for many Chinese policymakers. This suggests that US policymakers should not expect changes in Chinese leadership to generate seismic shifts in Chinese foreign policy. China’s identity as both a victim of Western imperialism and a reemerging great power will remain the foundation for decision-making, even with positive or negative pressure from the West.

Given the relative stasis of Chinese foreign policy goals, China’s newfound capability to advance its critical interests under Xi’s leadership is the key difference from previous administrations. If China’s identity remains consistent, understanding China’s perspective on its capacity to achieve foreign policy goals is vital for Western states, as is the ability to shape China’s perception of its own capabilities.

Therefore, Western states’ China policy should focus on forcing China to question its capacity to act in international affairs. If Russia, for instance, were to lose the war in Ukraine, China might then question its capacity to defeat Taiwan in armed conflict. Moreover, if the United States were to lead on critical global issues such as climate change, China may question its capacity to lead in these areas. Chinese policymakers would view the cost of counteracting a fully engaged United States as beyond China’s current ability. While US leadership could use direct economic and military competition with China to change Beijing’s policies, this would feed into the Chinese identity as a victim of Western aggression. Compared to policies aimed at “countering China,” engaged US leadership on global issues is a far more effective strategy that would force China to exercise restraint without reinforcing China’s identity as a victim of the West.

. . .

Dr. Niall Duggan is a Senior Lecturer in international relations at University College Cork, Ireland, where he has taught in the Department of Government and Politics since 2015. His research interests include emerging economies in global governance, international relations of the Global South, and China’s foreign and security policies, mainly focusing on Sino-African and Sino-EU relations.

Image credit: UN Geneva, Flickr, via CC-BY-ND-NC 2.0.

Recommended Articles

Africa accounts for approximately two percent of global air travel. Given the continent’s vast size and large distances between major trade hubs, enhancing intra-African air connectivity will be…

An estimated 7.9 million Venezuelans migrated abroad for the long term under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule as Venezuela’s political, economic, and social crises have deepened. Alongside rising Venezuelan migration, migrants…

Amid stalled U.S. federal climate engagement and intensifying transatlantic climate risks, subnational diplomacy has emerged as a resilient avenue for cooperation. This article proposes a Transatlantic Subnational Resilience Framework (TSRF)…