Title: The Impending Danger of Informal Economic Coercion in Africa

China has frequently used informal economic coercion (IEC) to influence foreign governments to adhere to its foreign policy objectives. Given China’s focus on spreading its influence in the Global South, Africa faces extensive pressure from IEC. Notably, since the creation of China’s new Hunan model, Africa’s food sectors face the greatest threat of Chinese coercion. The United States must recognize that there are crucial regions of competition with China other than the Indo-Pacific and acknowledge the importance of economic statecraft in developing dependencies that bring states closer to China. In Africa, the United States needs to expand its diplomatic and economic presence by promoting sustainable development projects under an alternative model that counters China’s.

With the growing economic rivalry and weaponization of trade between China and the United States, economic statecraft has transformed into a new arena of great power competition. The United States remains deeply concerned about China’s economic rise, and the use of informal economic coercion (IEC) has drawn significant attention in the US policy world. China has used IEC measures, which target trade relations and are designed to spark disruptions in targeted countries, to retaliate against states that China believes violate its sovereignty and domestic affairs. China has also not established a formal legal framework for its unilateral coercive economic actions and often relies on selectively enforcing regulations.

China’s growing use of predatory economic coercive mechanisms, such as restricting imports, exports, and tourism, downgrading relations, sponsoring popular boycotts, and issuing empty threats of retaliation, to pressure foreign governments and companies to comply with Beijing’s objectives have prompted different responses across various regions. The West has developed measures against Chinese economic coercion, including the EU’s Anti-Coercion Instrument, which took effect in December 2023, and the US government’s new State Department team—informally known as “The Firm”—which advises countries targeted by China. In contrast, other regions of the world have not developed official mechanisms to address these practices. This relative lack of preparedness is especially evident in Sino-African relations. Beijing has provided financial loans and credits for infrastructural projects to more than 32 African nations, raising the continent’s debt to $93 billion. Despite Western criticism of China’s narrow definition of development as poverty reduction when evaluating programs, failure to establish institutions that encourage transparency and facilitate sustainable development, and poor labor practices in partner states, China has continued to promote the idea of a partnership of equals in its engagement with African countries. Indeed, African countries have widely accepted Chinese investments in the region, often pointing to the export advantages that improved infrastructure brings.

What Does Chinese Informal Economic Coercion Entail?

The Mercator Institute for China Studies has identified 123 cases of Chinese IEC between 2010 and 2023, most of which have occurred in regions close to China, where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) aims to foster conformity to its political demands and core national interests. China generally imposes such measures after flash events or ongoing disputes with other states, including non-adherence to the One-China Policy, threats to Chinese citizens abroad, disruptions to Chinese economic security and supply chains, and the adoption of anti-China policies. Following these disputes, China often informally applies IEC mechanisms to target states in a way that ensures the CCP possesses plausible deniability and flexibility in adapting and withdrawing economic measures.

Where This Fits into Africa

While China has yet to explicitly use IEC mechanisms within Africa, its growing presence on the continent creates vulnerabilities and risks. China’s expanding influence over Africa targets key strategic areas such as agriculture, minerals, and infrastructure, with the latter primarily promoted under the Belt and Road Initiative. The CCP continues to invest substantial resources to gain a greater monopoly over the expanding agricultural sector, which makes up 32 percent of Africa’s GDP. China’s growing investment raises the question of whether China could leverage this economic coupling in the future, especially because the CCP identifies food security as an area of high importance in its fourteenth five-year plan.

In recent years, Africa’s economic growth has become increasingly dependent on exporting raw materials and agricultural products, which make up a sizeable proportion of the $282 billion in China-Africa bilateral trade. China has yet to weaponize its influence over Africa’s agricultural industries, but its new Hunan Model may provide new opportunities to do so. The model, named after the Southern Chinese province leading agricultural investment abroad, specifically focuses on deepening economic relations regarding agriculture, heavy industry equipment, mining, and metallurgy, areas Hunan also leads within China. The model is also part of the broader Chinese 2035 Vision for China-Africa Cooperation, which seeks to enhance agricultural productivity, technical assistance, and trade, among other areas.

The expansion of Hunan’s two national-level trade platforms—the China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo (CAETE) and the China-Africa Economic and Trade In-Depth Cooperation Pilot Zone—illustrates Hunan’s growing role in China’s engagement with Africa. These new methods of engagement have increased annual agricultural exports from Africa to China to $9 billion in 2023. They also have fulfilled their intended function of expanding Chinese industries abroad, with groups such as Changsha Construction Machinery Industry Cluster (consisting of industry giants such as Sany, Zoomlion, and Sunward Intelligent Equipment) rolling out hundreds of new products to African markets since 2021. This growing economic entanglement has increased Africa’s vulnerabilities to IEC by allowing China to effectively mobilize stringent quality standards and tariffs as methods of economic coercion.

Another cause for concern is China’s growing trade surplus with African countries, which is likely to expand under the Hunan Model. China and Africa traded $282.09 billion in goods in 2023, a 1.5 percent increase compared to 2022. However, Chinese exports to African countries rose by 7.5 percent to reach $172.78 billion in 2023, while Chinese imports from Africa dropped to $109.31 billion, reflecting a 6.7 percent decline. African leaders have criticized this imbalance and questioned whether China can continue to ensure mutually beneficial cooperation as its geo-economic influence continues to grow. For example, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has emphasized the need for balanced value-added trade, urging China to open its market to African products. Even South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who regularly participates in BRICS summits and boasts about friendly relations with Beijing, has called for narrowing down the trade deficit “that exists in China’s favour.” This concern is also a recurring topic in the two sides’ multilateral engagement through the annual Forum for China-Africa Cooperation.

Warnings for Africa Regarding Its IEC Vulnerability

Although the Hunan Model may offer a partial solution to these concerns in leveraging Africa’s agriculture market to counter growing trade deficits, these emerging ties also pose grave consequences for African states. In Asia, China has already employed IEC to punish states for unfavorable foreign policy decisions. For instance, after China’s April 2012 standoff with Philippine naval forces near the disputed Scarborough Shoal, China restricted banana imports from the Philippines, claiming they were tainted with pests. In September 2024, China ended tariff exemptions on 34 Taiwanese agricultural products after the United States announced diplomatic visits and a possible sale of aircraft spare parts to Taiwan.

Historically, IEC concerns have centered on threats to Africa’s natural resources and oil exports. However, these vulnerabilities have since evolved to include numerous food industries, infrastructure agreements, and technological companies. African leaders must be cautious to avoid further dependence on Chinese trade, which could prove detrimental in the long run. China’s rising domestic consumption and need for resources may compel President Xi Jinping to solidify China’s control over Africa’s emerging industries.

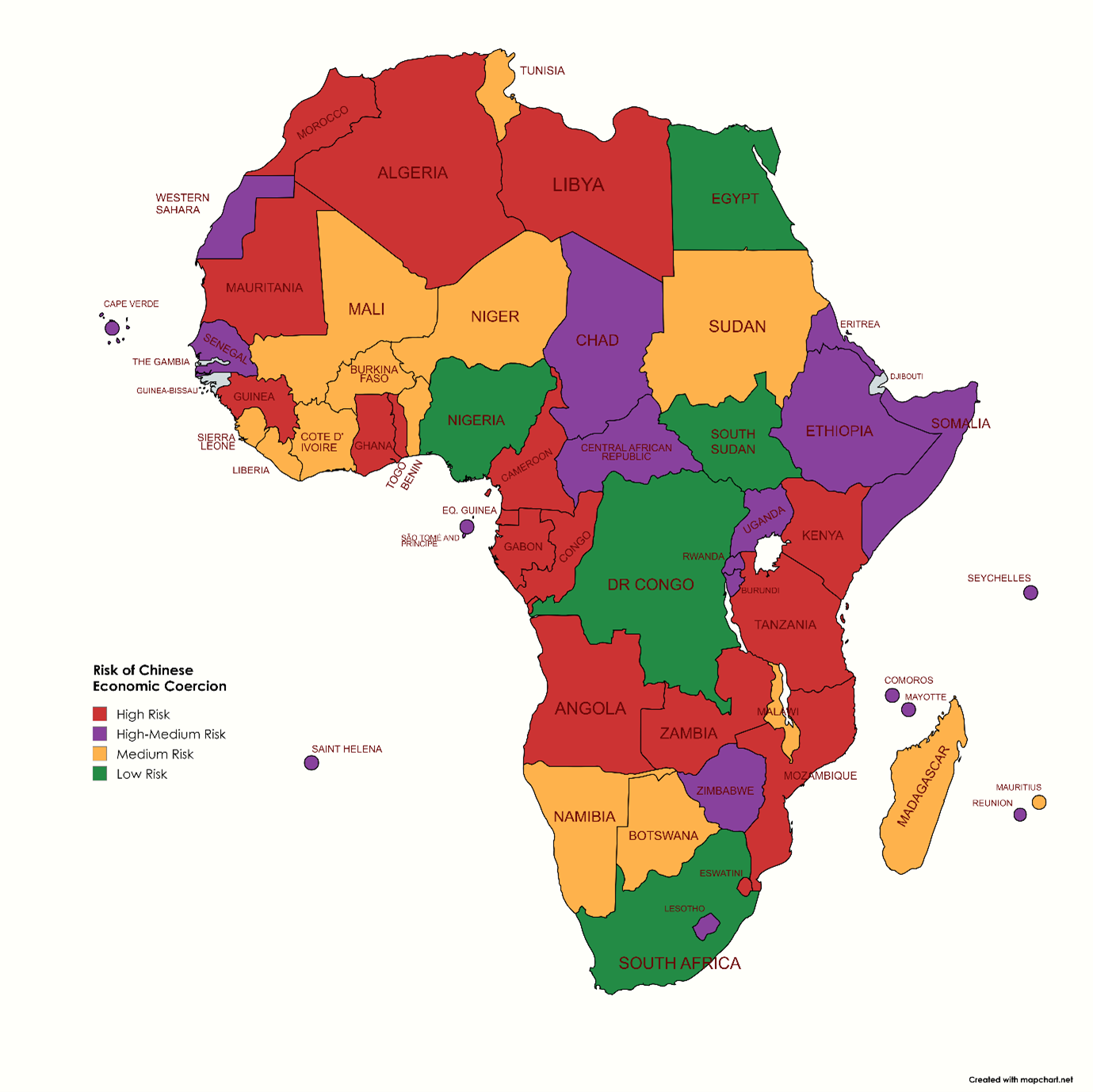

Eswatini has already faced Chinese IEC mechanisms twice, including state-issued threats and tourist restrictions barring Swazi citizens from Chinese embassies. China implemented both sanctions in response to Eswatini’s growing diplomatic relations with Taiwan. The accompanying map, based on trade and investment data gathered by the China-Africa Research Initiative, highlights the African states most vulnerable to IEC. Much of Africa remains in a perilous position, with China continuing to exert considerable influence over economic relations and development.

Source: Authors’ elaboration with data from the China-Africa Research Initiative at John Hopkins University.

Implications for the United States

Washington has already implemented measures to mitigate the dangers of Chinese IEC with the State Department’s creation of “The Firm,” which seeks to identify risks from China and support derisking measures in the United States and abroad. Although the forthcoming department’s capabilities cannot be ascertained yet, its predicted preemptive denial strategy—including cooperation with allies via sharing information, reinforcing vulnerabilities, and developing response mechanisms—is a positive step toward mitigating China’s actions. However, this small department’s consultancy status will likely be insufficient to effectively contain incidents of Chinese IEC.

In particular, the United States and other Western governments have disregarded the importance of Sino-Africa food cooperation via the Hunan Model. This cooperation remains indispensable to African economies and is a key conduit for Chinese influence on the continent, thereby enhancing China’s leadership status.

Except for monitoring teams, Western policymakers have not provided a competitive economic alternative to the Hunan Model, nor have they collaborated with the African Union to build institutions that promote transparency, addresse corruption, and contribute to regional growth and development. While the United States must prioritize the resilience of its own food supply chains amidst climate change and conflicts like the Russo-Ukraine war, it must also support international efforts to safeguard food supply chains against Chinese threats. Having seemingly retreated from Africa since 2011, the United States must once again foster greater opportunities for African states to reduce dependence on China by providing alternative economic solutions, prioritizing the restoration of weakened US-Africa economic ties. The United States should therefore follow through on its pledge to invest $55 billion in Africa, as announced during the US-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022, and expand its Prosper Africa initiative and the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). These initiatives are particularly crucial as a counterweight to the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, during which China committed to providing 360 billion yuan ($50.69 billion) to Africa over the next three years.

The upcoming US elections will significantly influence the direction of the United States’ China policy. A potential return to Trump’s mantra of securitizing US interests and taking retaliatory actions will likely undermine current long-term strategic efforts to invest in Africa and is unlikely to incentivize African leaders to decouple from Chinese actors. Conversely, greater continuity under the Democratic Party candidate, Kamala Harris, may result in the continued neglect of the growing threat posed by IEC, which remains on the periphery of US foreign policy. Therefore, the United States should continue strengthening preemptive denial tactics while ramping up efforts and funding to prevent African dependency on China. Only through such strategic adjustments can the United States counteract Chinese IEC on the world stage.

. . .

Jonathan Sebborn is a postgraduate student in International Relations at the University of Exeter, specializing in Chinese foreign policy and African development politics.

Maria (Mary) Papageorgiou is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow at Newcastle University in the UK. Before that, she taught at the University of Exeter, UCL, and SOAS University of London. Her areas of expertise include China as a great power, its engagement in the Middle East, and Sino-Russian relations.

Image credit: Paul Kagame, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

Recommended Articles

This article compares U.S. and Chinese approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) exports in Africa and examines how these disparate approaches have produced both downstream benefits and challenges for the region.

On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly unanimously adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, an international treaty designed to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and…

As the Trump administration proposes a sweeping overhaul of the US foreign assistance architecture by dismantling USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and restructuring the State Department, there is an…