Title: Gender Trolling: Digital Manosphere and Misogyny in China

This article discusses gender trolling in China’s media culture, exploring the tension between feminist activism, digital platforms, and state ideologies. It highlights how the growing digital manosphere and exclusionary feminist practices contribute to a hostile public sphere while emphasizing the need for alternative forms of feminist organizing that prioritize empathy, personal connection, and contextual understanding. The analysis calls for reevaluating digital spaces and offline resistance in fostering a more inclusive and just future.

Introduction

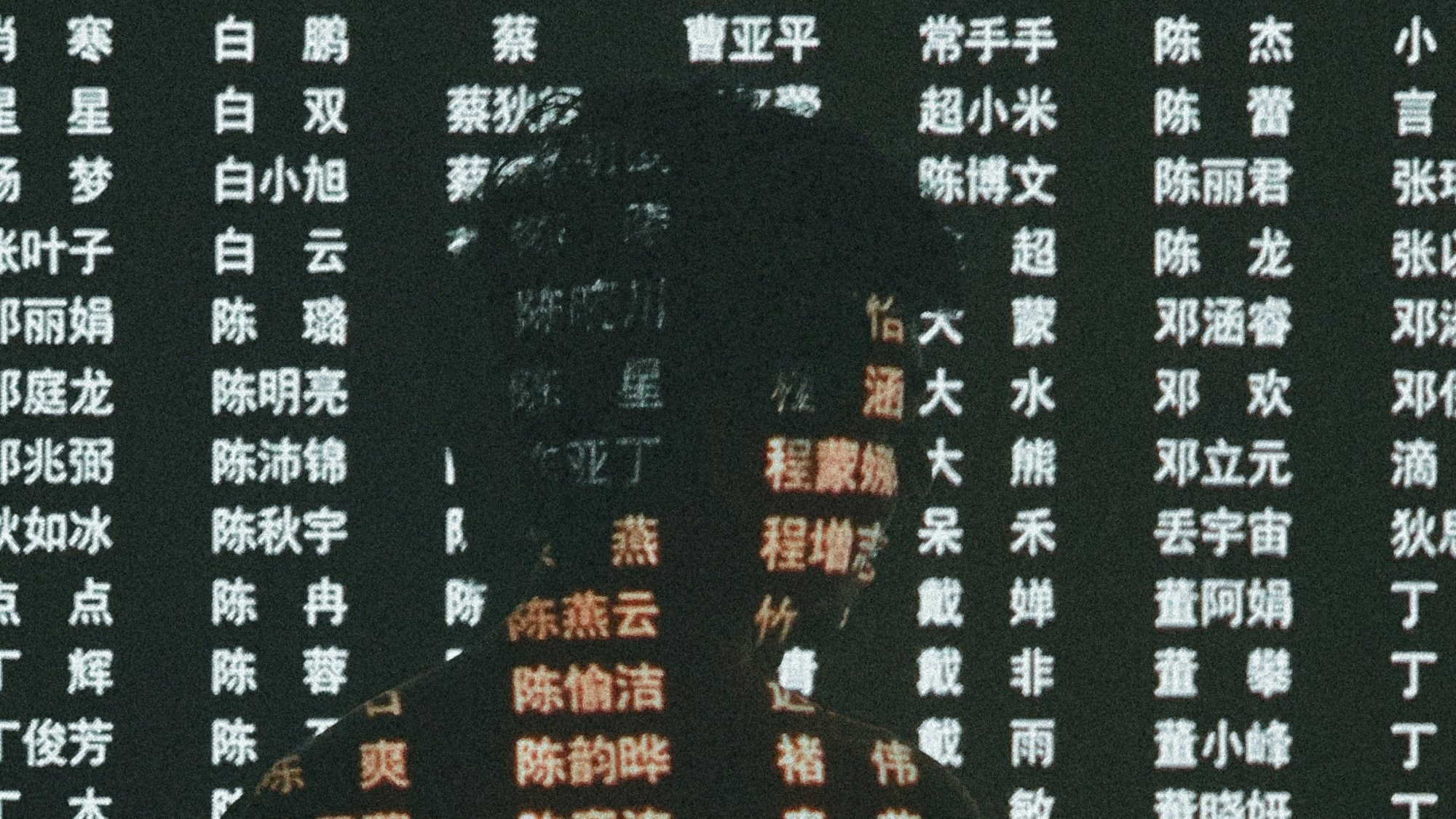

Trolling is a form of targeted harassment deemed deviant, offensive, and obscene. In the digital environment, gender trolling disproportionately targets women and is fueled by sexism, misogyny, and patriarchal norms. From the rise of the digital manosphere—fragmented online communities on websites, blogs, vlogs, social media accounts, forums, and Wiki pages spreading anti-feminist and misogynistic ideologies—to the weaponization of feminism against individuals, the culture of gender trolling reflects the entanglement of online entertainment, political ideology, and platform economy.

The discourse surrounding the Chinese movie Her Story (《好东西》(literally translating to “good stuff”) by female director Shao Yihui exemplifies how gender trolling manifests in modern online discourse in China. Acclaimed as the Chinese Barbie for its women-centered narrative, it became a box office hit and sparked polarized discussions on feminism and gender roles. The heartfelt portrayal of a single mother and a free-spirited single woman deeply resonated with much of its female audience, who appreciated its depiction of women’s experiences across different stages of life. However, it was met with criticism by predominantly male anti-feminist viewers, who accused it of pandering to “political correctness” and promoting women’s empowerment at the expense of men. The controversy deepened when Shao faced backlash from her feminist fans for liking a post on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, criticizing retired gymnast Wu Liufang for sharing sexually provocative content on Douyin, China’s TikTok. Shao’s “like” was framed as a betrayal of feminism, as the comment condemns women’s self-sexualization for men’s attention. The dual backlash—criticizing Shao’s feminist framing in the film and questioning her perceived ideological loyalty—illustrates the fraught dynamics of digital media and public discourse in China. Her Story and its surrounding controversy highlight how gender trolling has become both a weapon and a symptom of an online culture rife with polarization, where meaningful dialogue is often drowned out by hostility and misinterpretation.

This piece examines how gender-based harassment has become both a tool of ideological control and a form of digital spectacle, while also exploring alternative feminist organizing strategies that emphasize care, solidarity, and quiet resistance in the face of an increasingly hostile media environment.

Digital Manosphere: From Fringe to Mainstream

China’s internet, like many others, is rife with contentious gender debates and frequent instances of trolling, often targeting outspoken figures like Shao. Another prominent example is standup comedian Yang Li, who gained fame in 2020 with her sharp critique of male entitlement, coining the term puxinnan (普信男, meaning “average yet confident men”). While her humor made her a cultural phenomenon, her appearances in commercials garnered controversy, primarily as a result of backlash from men accusing her of being sexist, “anti-men,” or misandric. Her fans have even been referred to as “the Ta-li-ban”—playing on the homophony between her given name and the Taliban, the Afghan terrorist group known for gender-based violence.

A major driver of such gender trolling is the growing digital manosphere. Mirroring global trends, the Chinese manosphere thrives on platforms like Weibo, Bilibili (a top video streaming site), Zhihu (China’s Quora), Hupu, and Douyin. Voices in the manosphere have analyzed and critiqued feminist movements and women’s rights advocacy, drawing examples from neighbors such as Japan and South Korea. They are also known for commenting and distorting the focus on domestic gender issues by framing men as victims and employing inflammatory rhetoric against Chinese women. Another stark illustration of such online trolling is the forum Sun Xiaochuan Ba, or Sun Ba, notorious for its aggressive harassment of women. This 4chan-like space has become a hub for China’s digital manosphere or incel-type misogynists, where millions of male users exchange personal information about women, target feminists, and orchestrate doxing and cyberbullying campaigns. Victims range from public figures and survivors of gender-based violence to random women trolled for amusement or ideological spite.

The manosphere frames men as social underdogs, blaming women’s rights movements for undermining their roles and justifying trolling as a way to reclaim their perceived loss of rights to feminist “privileges.” For example, a university student’s report on “18 women’s privileges” ignited controversy by arguing Chinese society favors women over men, citing gendered differences in retirement ages and physical fitness test standards.

Anti-feminist trolling gains further traction when intertwined with populist nationalism in racial and gendered contexts. Prominent nationalist bloggers exploit this sentiment, portraying feminism as a Western concept that threatens traditional Chinese gender norms to bolster state-aligned narratives. In March 2021, feminist activist Xiao Meili shared a Weibo video confronting a man smoking in a hotpot restaurant. The incident quickly trended on Weibo but shifted from a public health issue to portraying feminists as instigators of social conflict and gender antagonism. Patriotic influencers sparked a widespread populist and nationalist attack on Xiao, involving doxing, slut-shaming, and insults, with accusations of her colluding with “anti-China foreign powers” to undermine national security and the safety of citizens. This alignment of misogyny with nationalism reflects a troubling collusion between the platform economy and state ideology—trolls amplify anti-feminist narratives to boost engagement while championing cultural confidence in China’s political system and national achievements for increasing their own cultural and economic capital.

Weaponized Feminism in a Digital Environment

Gender trolling is not exclusive to the manosphere; feminist activists have also leveraged trolling tactics to challenge misogyny. For instance, feminist groups have promoted a mirroring strategy, “simply replacing the words ‘women’ with ‘men’” to critique and subvert patriarchy, creating a provocative feminist counter-public. Chinese feminists parody misogynistic language, using terms like puxinnan (average yet overconfident men) or bug-men (guonan, phonetically echoing “this country’s men”) to expose the absurdity of gendered insults. While controversial, such mimicry demonstrates how trolling can be repurposed to challenge systemic oppression.

Yet, this same confrontational language is increasingly turned inward. As seen in the backlash against director Shao Yihui, feminist rhetoric is sometimes weaponized, not to challenge systemic oppression but to attack individuals, replicating the very harm it seeks to dismantle. This internal policing often draws stark lines between “good” or “bad” feminists, enforcing exclusionary politics. In China, this weaponized feminism shows up in heated online debates about gender: married women are reduced to submissive, burden-bearing laborers or called “married donkeys;” celebrity feminist mothers face backlash for giving their children the father’s surname, seen as submitting to patriarchy; feminists are expected to oppose surrogacy to maintain their “feminist citizenship.” Much of this discourse circulates within communities like jinü (激女), which grows out of the 6b4t movement inspired by South Korean radical feminism and largely advocates for gender separatism. However, the aggressive tone is not so exceptional but rather native to the unique political economy of media in China, where platform algorithms reward confrontation while skirting politically sensitive critique.

Amid tightened state control and official narratives framing feminism as extreme or foreign-influenced, weaponized feminism offers a safer outlet: it targets individuals, not institutions or states. Meanwhile, the commercialization of gender topics, particularly for the digital economy, serves feminist consciousness-raising campaigns, effectively manipulates public opinion, and profits from selling empowerment and choice feminism to consumers. The commodified feminism raises awareness yet flattens political engagement, offering consumption as the way to feminist resistance. Combined with the anonymity and fleeting nature of online interactions, weaponized feminism becomes a form of bottom-up ideological policing: excluding individuals and “purifying” the feminist community while amplified by algorithms, platform economy, influencers, state ideology, and media users’ willing and willful participation. The aforementioned Shao’s case exemplifies how feminist language is repurposed to enforce conformity, not critique power.

Such a media environment easily manufactures gender spectacles filled with trolling and hatred, transforming them into entertainment that provokes emotions and boosts ratings. In the show Goodbye Lover 4, which intends to explore the challenges and struggles of marital relationships, Mai Lin, the wife of an out-of-fashion singer, became the target of intense shaming, harassment, and cyberbullying from viewers due to perceived inconsistencies and manipulative behaviors. Underlying such relentless and humiliating criticism of a single woman is a new era of entertainment, where trolling is one of the best effects for show businesses and gender policing. Audiences are seduced to be entertained by the voyeuristic consumption of others’ lives, the manipulated realities in media, and the trivialization of human struggles.

Building Inclusive Spaces with Empathy

The rise of the digital manosphere and exclusionary feminist practices, compounded by China’s state-market complex, underscores the need for a more inclusive public sphere. Leveraging state-sanctioned discourses and offline organizing can offer strategic pathways for resistance in navigating digital commodification, censorship, surveillance, and restriction on feminist activism.

Integrating gender issues, particularly gender-based violence, into government-approved discourses in legal reforms has proven to be a practical and effective feminist digital mobilizing approach, possibly driving incremental change. In 2021 and 2022, the two consultations for the proposed revisions to China’s women’s rights protection law garnered over 80,000 people to contribute over 300,000 opinions and suggestions to the amendment, including further improvement on mechanisms for preventing and addressing sexual harassment and sexual assault. Digital mobilizing on social media platforms is vital in raising consciousness and guiding public participation in the legislative process. However, state priorities in these policies and the censorship risks of collective mobilization require feminist organizers to carefully navigate the limited space to push for meaningful change.

Given the risks of openly discussing controversial gender topics and challenging manosphere and state-sponsored misogyny, offline organizing remains crucial. Whereas digital mobilizing is still an option, traditional methods—such as small and intimate in-person gatherings, collective living experiments, and offline consciousness-raising—can offer safer spaces for constructive dialogue. These efforts should prioritize security, trust, and individual well-being over public confrontations, fostering safe environments for discussing gender issues without fear of surveillance and repercussions. These quieter forms of resistance, rooted in personal connection, contextual understanding, and empathy, are vital for building a more just and inclusive future.

. . .

Sara Liao is a media scholar and feminist who researches the intersection of digital media, feminism, globalization, and East Asian popular culture. She is currently working on her new book, Unpopular Feminism, which theorizes digital feminist activism and the culture of misogyny in the post-MeToo media environment in China.

Image Credit: Alvan Nee, Unsplash Content License, via Unsplash.

Recommended Articles

This article advances the idea that teaching children their mother tongues and learning adjacent national languages offers better prospects for consolidating nation-building and contributing to cultural preservation. Kenya’s case illustrates…

Despite the non-political positioning of its organizing body, the European Broadcasting Union, the Eurovision Song Contest plays an important role in shaping how the public imagines and understands ideas of…

Inuit across the Arctic have long witnessed dramatic environmental changes in their homelands. Their observations, deeply embedded in their relationship with the land and water, offer critical insights…