Title: February 28th, 28 Years Later: The Lasting Psycho-Social Impacts of Türkiye’s Hijab Ban

The 1997 hijab ban in Türkiye left lasting effects on Muslim women’s psychological, social, and religious identities, shaping their experiences across academia, bureaucracy, and politics. Evidence from interviews with 28 women working in academia, politics, and business illustrates how exclusion inflicted psychological, social, and spiritual harm while simultaneously fostering faith-based resistance. To prevent similar injustices, Türkiye must adopt policies that formally acknowledge the harms of the hijab ban, strengthen institutional protections for religious freedom, and invest in inclusive education and psychosocial recovery.

Introduction

On February 28, 1997, Türkiye experienced what became known as a “postmodern coup”—a military intervention that removed the government without the use of force—and institutionalized a hijab ban that profoundly altered the public presence of veiled women. What had been a personal expression of faith was transformed into a symbol of exclusion and political conflict. Nearly three decades later, debates over religious freedom, women’s rights, and authoritarian governance continue to define Türkiye’s political landscape, underscoring the enduring significance of this prohibition.

This article argues that the hijab ban demonstrates the dangers of coercive secularism: it traumatized citizens, fractured social cohesion, and undermined trust in the state, while paradoxically also generating strength, solidarity, and new forms of agency among the women it targeted. This argument is supported by a qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews with 28 women from academia, politics, and business who experienced the February 28 hijab ban. Their narratives, thematically analyzed and validated through expert review, illustrate how trauma, stigma, and symbolic violence shaped identity, resilience, and faith.

Historical and Political Background

The hijab has long been at the center of Türkiye’s struggle to balance secularism and religious expression. Shaped by the state’s interpretation of secularism, the hijab became marginalized as a symbol of anti-modernism and lower socioeconomic status. For much of the twentieth century, state elites regarded the veil as a threat to modernity. By the 1990s, this cultural suspicion hardened into policy. The February 28 coup codified restrictions on veiling, excluding veiled women from universities, public service, and politics.

This prohibition was not merely a bureaucratic matter. It rendered veiled women hyper-visible as symbols of political Islam and simultaneously erased them from public life. Media portrayals criminalized their presence, associating the hijab with extremism. One infamous episode—the “Fadime Şahin incident” staged in 1996—amplified public anxieties about veiling and framed religious women as threats to the republic. Thus, when the ban came into effect, it was experienced not only as a denial of rights but also as a stigmatization of identity.

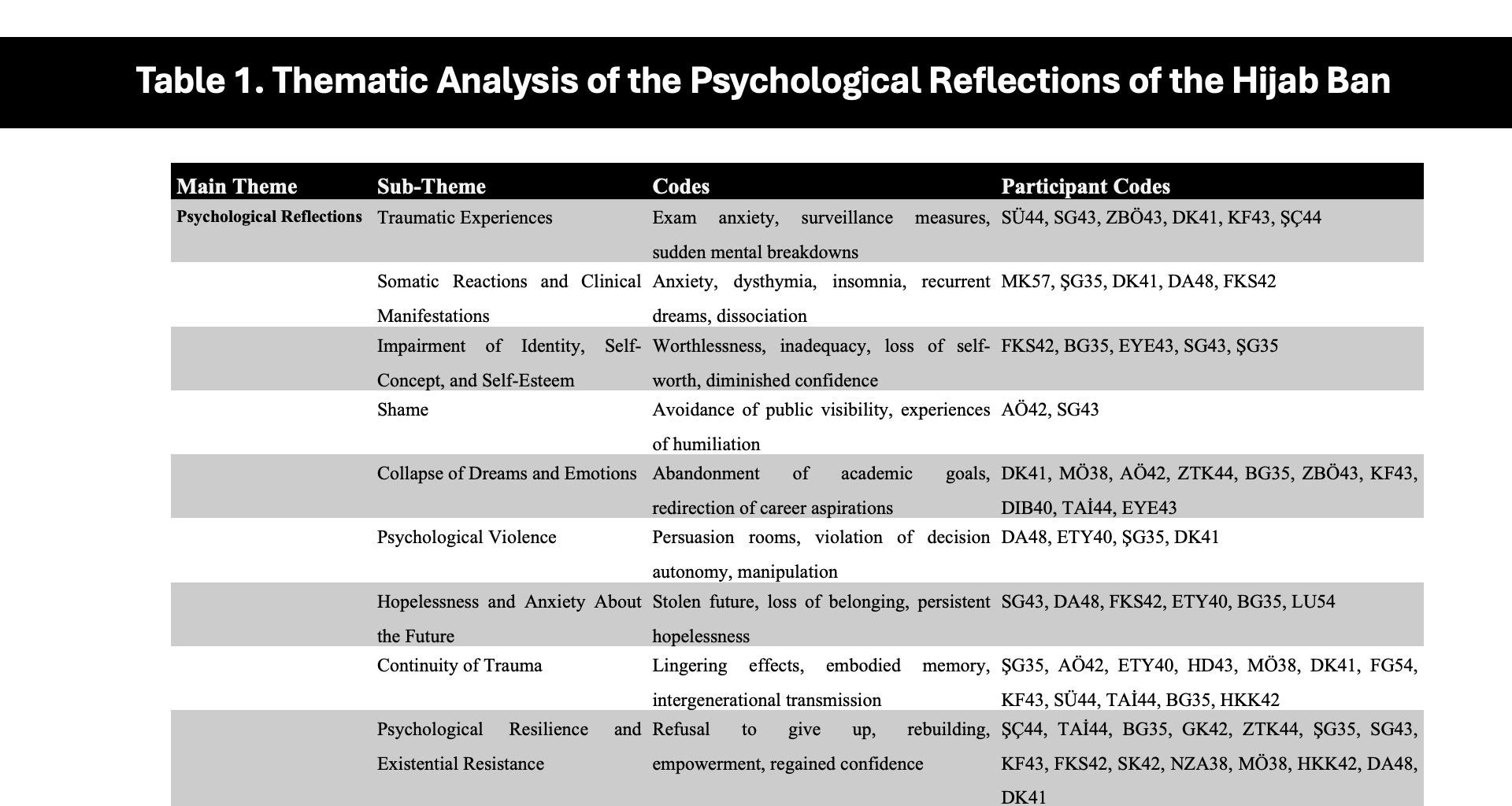

Psychological Consequences: Trauma and Resilience

For many of the women interviewed, the hijab ban represented a personal crisis. Denied the ability to attend university, sit for exams, or enter workplaces, they experienced what trauma theorist Ronnie Janoff-Bulman calls “shattered assumptions”: the collapse of fundamental beliefs in fairness, safety, and belonging. One participant recalled the devastation of receiving a rejection letter stamped with the words “You have not been placed in any institution.” Another described hair loss and chronic anxiety linked to the stress of hiding or removing the hijab.

The trauma was embodied. Women spoke of sitting in the back rows of lecture halls to avoid scrutiny or hiding behind billboards to shield themselves from stares. These are not isolated anecdotes but consistent with sociologist Erving Goffman’s concept of stigma and Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic violence—the subtle, systemic enforcement of social exclusion.

And yet, psychological suffering was not the whole story. Several participants described themselves as “pruned but stronger,” acknowledging that adversity had paradoxically deepened their resilience. The ban, they argued, had stripped away illusions of state protection but forced them to develop new sources of confidence rooted in faith, family, and community. This dual legacy—trauma and resilience—underscores how coercion can wound but also galvanize resistance.

Table 1. Thematic Analysis of the Psychological Reflections of the Hijab Ban

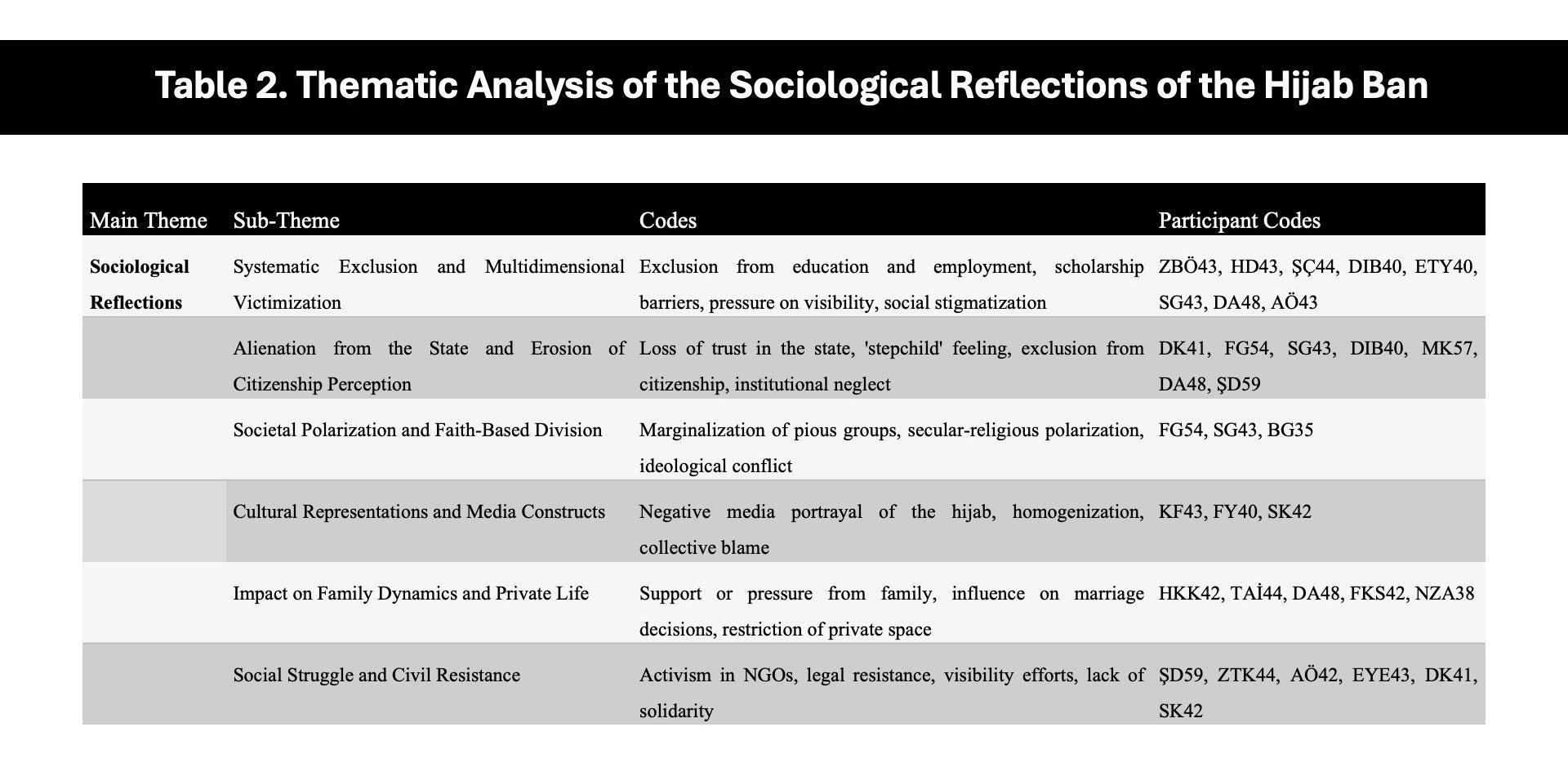

Sociological Consequences: Exclusion and Polarization

Socially, the hijab bans entrenched exclusion at multiple levels. Participants described being labeled “hooded girls” or“ninjas,” terms that reduced them to caricatures. In universities, they were barred from entering classrooms; in government, they were treated as disloyal citizens. One woman summarized the experience succinctly: “We were stepchildren of the homeland.”

This sense of alienation eroded trust in state institutions, deepening the divide between secular and religious communities. Families responded ambivalently—some rallied to protect their daughters, while others pressured them into marriage or discouraged resistance for fear of reprisal. These dynamics highlight how authoritarian secularism not only excluded women from public institutions but also restructured private relationships, shaping life trajectories in profound ways.

Yet exclusion also sparked activism. Many participants became active in NGOs, volunteered in rights organizations, and worked to redefine intellectual discourse. Instead of disappearing, they created spaces for civil society, often led by women. In this sense, the ban polarized society but also gave rise to new forms of civic participation, challenging the state’s monopoly on legitimacy.

Table 2. Thematic Analysis of the Sociological Reflections of the Hijab Ban

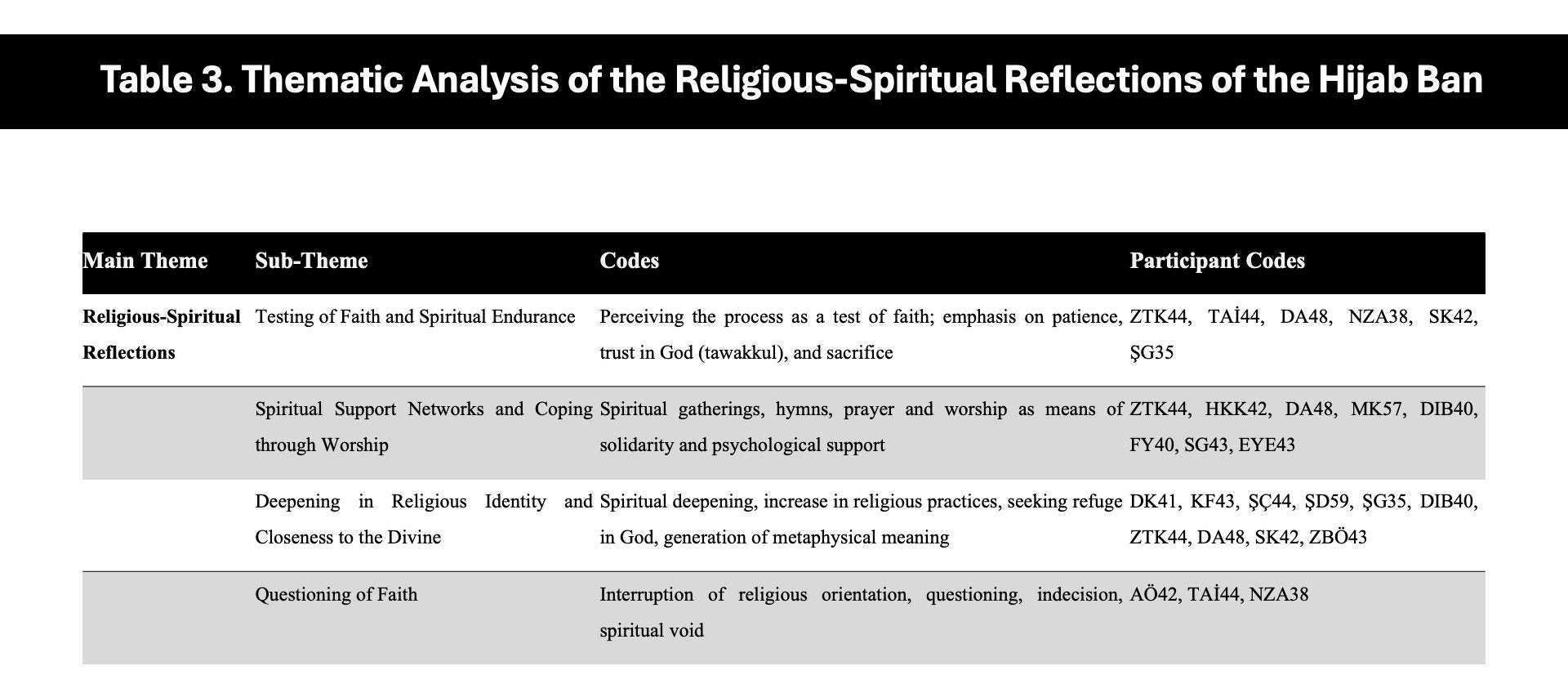

Spiritual and Religious Consequences: Rupture and Resistance

Perhaps the most intimate consequence of the hijab ban was spiritual. For women who saw the hijab as a reflection of their faith, being compelled to remove it felt like a separation between their identity and their beliefs. Some individuals expressed feelings of shame and doubt, questioning their worth as believers. Others mentioned confusion and a delayed reconciliation with their religious practices.

At the same time, participants highlighted how religious communities both provided support and contributed to conflict. Discussion groups and prayer networks offered solidarity. Some participants described being held in coercive ‘persuasion rooms’—spaces where students wearing headscarves were subjected to verbal pressure and threats in one-on-one meetings with university administrators aimed at forcing them to remove their headscarves—experiences that intensified their suffering, though they coped with them through the support of religious communities. In line with psychologist Kenneth Pargament’s theory of positive religious coping, women transformed suffering into a reaffirmation of belief. For many, the hijab itself became more than an article of clothing; it was a flag of resistance carried against authoritarian repression.

Table 3. Thematic Analysis of the Religious-Spiritual Reflections of the Hijab Ban

Redefining Citizenship

These findings reveal an intriguing paradox. The hijab ban aimed to exclude women from the public sphere, yet it unintentionally fostered new forms of agency. Women who had been denied entry into universities later became academics, journalists, and politicians. Their activism redefined the terms of debate about citizenship, secularism, and gender.

One striking pattern is how participants reframed exclusion as empowerment. “They tried to erase us,” one woman explained, “but we learned how to write ourselves back into history.” This perseverance complicates narratives of victimhood. While trauma and stigma were undeniable, they coexisted with defiance and creativity, reminding us that marginalized groups are never passive recipients of power but active agents in reshaping it.

Policy Lessons for Today

Although some commentators contend that the hijab ban was necessary to safeguard secularism and women’s equality, and that the tenacity women later displayed suggests its harm was limited, this reasoning is flawed. It confuses coercion with secularism, which in a democratic context should mean neutrality and equal citizenship, not exclusion based on religious expression. Moreover, this fortitude does not erase the trauma, stigma, and symbolic violence women endured. As the evidence shows, the ban fractured trust in the state and deepened social divisions rather than protecting democracy.

To move forward, Türkiye must confront the legacy of the hijab ban through deliberate policy choices that acknowledge harm and prevent its repetition. A formal state apology and symbolic measures would help rebuild trust, while stronger legal protections are needed to guarantee religious freedom and equal citizenship. Universities should be safeguarded as inclusive spaces, and psychosocial support provided to address the long-term trauma women continue to carry. At the same time, empowering civil society organizations—particularly women’s groups—can foster dialogue across social divides and strengthen democratic participation.

Conclusion

The February 28 hijab ban was more than a dress code regulation; it was experienced by participants as a direct assault on religious identity with enduring psychological, social, and spiritual consequences. While many women transformed trauma into defiance and faith-based agency, others continue to carry psychological wounds and disrupted educational and career paths. The persistence of these effects demonstrates that authoritarian measures against religious expression not only marginalize citizens but also erode trust in state institutions.

The structural reforms introduced under the Erdoğan administration—including constitutional and legal amendments and the dismantling of public barriers—significantly alleviated the adverse effects of the ban by curbing military tutelage, reinforcing civilian authority, and broadening religious and civil liberties through reforms aligned with the EU’s democratization agenda. However, since full confrontation and acknowledgment have not taken place across all segments of society—particularly within elitist secular bureaucratic and social circles—the collective trauma continues. Public apologies and symbolic reparations remain essential for restoring trust between citizens and the state. At the same time, women’s faith-based resistance has enabled them to achieve subjecthood and assert new roles in academia, politics, and bureaucracy, paving the way for a significant transformation in the reshaping of Türkiye’s public sphere and enabling substantial progress in this process. To consolidate these gains, policymakers must also ensure that future state policies do not reproduce similar forms of exclusion, thereby fostering an environment of inclusion, justice, and democratic resilience for future generations.

…

Saliha Uysal is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology of Religion at the Faculty of Theology, Istanbul University. She is the author of Awakening to Death: Near Death Experiences (in Turkish: “Ölüme Uyanmak: Ölüm EşiğiDeneyimleri”) and From Tradition to Future Islamic Psychology (in Turkish: “Gelenekten Geleceğe İslami Psikoloji”) and has published widely on religion and psychology. Her recent work includes a 2019 study on the psychological effects of Islamophobia and the hijab ban in Türkiye.

Image credit: Pavel Danilyuk via Pexels

Recommended Articles

Africa accounts for approximately two percent of global air travel. Given the continent’s vast size and large distances between major trade hubs, enhancing intra-African air connectivity will be…

An estimated 7.9 million Venezuelans migrated abroad for the long term under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule as Venezuela’s political, economic, and social crises have deepened. Alongside rising Venezuelan migration, migrants…

Amid stalled U.S. federal climate engagement and intensifying transatlantic climate risks, subnational diplomacy has emerged as a resilient avenue for cooperation. This article proposes a Transatlantic Subnational Resilience Framework (TSRF)…