Title: Criminalizing Ecocide: A Conversation with Stop Ecocide International’s CEO Jojo Mehta

In this interview, GJIA sits down with Jojo Mehta, Co-Founder and Chief Executive of Stop Ecocide International, to discuss the global movement to codify ecocide as an international crime. Mehta helps contextualize ongoing environmental degradation within the larger frameworks of international law, corporate accountability, and global cultural mobilization.

GJIA: For readers who may be unfamiliar with the term, what is “ecocide”?

Jojo Mehta: Ecocide refers to the most severe, widespread, and long-term harm to nature. While environmental laws and regulations exist worldwide, they are largely fragmented, piecemeal, and insufficient. Our organization works to advance legislation to criminalize ecocide, meaning that the most serious damage to the living world would be treated as a crime. Introducing ecocide into criminal law would not only provide foundational support to the diverse body of law but also help fill gaps and establish a much stronger deterrent against major environmental harms.

GJIA: Part of Stop Ecocide International’s mission is to see ecocide recognized under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Yet, the ICC has historically struggled with enforcement. What mechanisms do you believe will ensure ecocide charges are pursued and not simply symbolic?

JM: There are a number of reasons why we aim to have ecocide recognized at the ICC, even as we also support national and regional progress. Our mission is to have the most severe harms recognized as serious crimes in as many jurisdictions as possible. The ICC already prosecutes atrocity crimes, and if we aim to elevate severe environmental harm to that level of seriousness, it offers the appropriate framework for doing so.

Another reason is practicality. Some people have asked why we do not pursue a standalone international convention on ecocide. While this would undoubtedly be valuable, it would take a long time. For example, a convention on crimes against humanity has been sitting on the shelf for decades. By contrast, the Rome Statute is an already existing document with an amendment mechanism that has been successfully used before. Pursuing an ICC amendment is therefore a comparatively practical and efficient path forward.

A further consideration is coherence. If we were to push for ecocide laws to be adopted in a given jurisdiction, particularly in large economies, we might spend years navigating different ministries. Even then, legal definitions could differ considerably from country to country. By first establishing ecocide as an international crime, states that ratify the amendment will share a legal framework.

Regarding enforcement, the ICC was designed as a court of last resort. Its role is to step in when national courts cannot or will not prosecute. For existing crimes under the ICC, such as genocide or war crimes, national prosecution is rare because states committing such crimes are unlikely to prosecute themselves. The ICC then becomes the court of first resort. By contrast, ecocide typically stems from reckless corporate actions rather than state directives, meaning most cases would fall under national jurisdiction. In this way, ecocide would restore the ICC to its intended complementary role.

GJIA: Given that key emitters like the United States, China, India, and Russia are not parties to the ICC, how does their absence shape the prospects for enforcing ecocide law globally?

JM: It is true that some of the most polluting states are not members of the ICC, which has both pros and cons. One advantage is that, since they are not parties, they cannot vote against the inclusion of ecocide. Unlike the United Nations, the ICC does not have a Security Council or a veto system; it operates as a pure numbers game. This structure gives small states—for example, small island nations acting together—significant leverage.

Generally, the states driving the ecocide agenda tend to be victims of ecological damage. For example, Vanuatu, at the frontline of climate impacts, has been a champion of ecocide law for years. Vanuatu has been leading on a number of legal initiatives, such as the International Court of Justice advisory opinion campaign and the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. They may be small in size, but in the diplomatic world, they punch well above their weight. Now, the Democratic Republic of Congo has joined in its support from the perspective of protecting its threatened rainforests, often referred to as the world’s “second lung.”

Of course, there are also disadvantages. If ecocide occurs in a country like the United States, the ICC can not intervene directly. However, even then, if the harm affects a state that has ratified the law, that state may have jurisdiction over the perpetrators.

Ultimately, we support efforts to criminalize ecocide in all jurisdictions. Our strategy has been identifying states that can take action rather than focusing on the large emitters. While those major emitters are not directly relevant to ICC work at this stage, they are not excluded from the broader conversation.

GJIA: Why do some states strongly advocate for recognizing ecocide while others remain hesitant or resistant?

JM: A key factor in the rapid acceptance of ecocide law is the definition itself, which resulted from a drafting program commissioned in 2021. The definition focuses on the level of harm, not on specific activities or sectors. Similar to how criminal law works, a murderer is defined by the outcome, not the method. The ecocide definition emphasizes the harm caused rather than forbidding particular activities. It does not prohibit industrial fishing or mineral mining; rather, it outlines a threshold of harm that should not be crossed. This approach encourages best practices without alienating any sector, which has been hugely helpful in facilitating constructive dialogue. So, while there are countries that are not ready to support ecocide, we have not encountered many that openly oppose it.

Moreover, as an organization, we maintain strict political neutrality. In a polarizing geopolitical context, we report on conversations at the state level without taking positions ourselves. This neutrality allows us to engage diplomatically with all states and help keep the conversation moving forward.

GJIA: Given the role of corporate actors in large-scale environmental destruction, what approaches have been most effective for engaging private-sector actors in ecocide discussions?

JM: In recent years, we have seen, unsurprisingly, growing engagement from the sustainable business sector. Companies that have long invested in responsible practices have been at a disadvantage, because typically money flows towards the cheapest and most environmentally harmful operations. Ecocide law represents a major leveling of the playing field. It ensures that whatever business you are in, your activities must not cause severe environmental harm. Those already operating sustainably are therefore better positioned because they have been preparing for this standard.

What has been particularly interesting is the response from the investment world. For several consecutive years, the International Corporate Governance Network submitted statements to the UN Climate Conferences advising governments to legislate for ecocide. They recognize that environmental degradation is a risk factor. In an increasingly volatile world, investors need to know that their capital will still hold value ten years from now. A company engaged in severe environmental harm represents future liability.

Criminalizing ecocide carries a different weight in the corporate world than regulatory law. Much of existing environmental law is highly technical, detailed, and prescriptive. In practice, companies that can afford it often learn to navigate or manipulate those rules. Effectively, if there is a category of something that is not supposed to be done, then they will recategorize that activity. If the regulation sets an emissions limit, companies will push or just consistently operate at the upper limit.

Criminal law forces decision-makers to ask, before signing off on a major project: is this going to create severe harm? And if so, could I be personally criminally liable? That question is a powerful deterrent. It prompts executives to seek alternative approaches or establish clear operational boundaries. Additionally, the accusation of criminal behavior can damage both a leader’s personal reputation and the company’s value. Stock prices can fall immediately. There is a rational deterrence provided by the criminal aspect that simply does not exist in the regulatory sphere.

GJIA: Beyond formal law, how can broader public awareness and cultural mobilization help shift the perception of large-scale environmental destruction? In other words, how can ecocide become common knowledge?

JM: It really is an organic process. People often say they want to “start a movement,” but you cannot manufacture one. A movement happens around an idea that the public relates to. That is what happened with ecocide law. We did not set out to build a movement. We articulated a demand, talked about it publicly, and it spread because people recognized its value. Interestingly, legislative progress is way ahead of public knowledge, which is unusual and, in many ways, a nice place to be.

Our organization works on two levels. First, we support the diplomatic process: providing information, connecting stakeholders, advising, and briefing states interested in advancing ecocide law. Much of this involves working in a supportive and advisory role with legal advisers and diplomats.

Second is the public-facing narrative. We serve as a key source of information on global developments related to ecocide law. When something becomes public, we help amplify it and connect the dots between progress happening in different arenas—policy, business, faith communities, civil society campaigns, and more. The public conversation helps reinforce the legislative process.

Your question also touches on the sister goal in criminalizing ecocide, that is, making ecocide a cultural taboo. We urgently need a taboo around the mass destruction of nature. So, normalizing the language of ecocide contributes to building that cultural boundary.

GJIA: What are the key priorities for Stop Ecocide International in the year ahead?

JM: We have the ICC Assembly of States Parties ahead, where we will again have a presence and support state-led side events.

Broadly, one of our main priorities is helping people connect the dots between ecocide law and other areas of law, cultural perspectives, and existing environmental and criminal provisions aimed at preventing harm. We are encouraging a more holistic understanding of how ecocide law fits within broader international legal and institutional frameworks.

Part of that means engaging with different UN bodies that, while not directly responsible for mandating criminal law, are deeply relevant. For example, the UN Environment Programme’s mandate to protect the environment makes ecocide a natural topic; similarly, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime addresses transnational organized crime, which overlaps with many environmental harms. The idea is to integrate ecocide into conversations already underway across the UN system.

One of the areas of connection we are exploring is with outer space. Space is being rapidly commodified and militarized, and ecocide law could become one of the few legal tools to help govern activities there. Similarly, we are looking at global commons. The so-called “tragedy of the commons” is really a tragedy of misunderstanding and lack of legal protection. Commons function well when proper legal frameworks are in place. Ecocide law could be a key part of that.

Overall, developments are moving twice as quickly as we could have predicted. We expect that within five years, most of the world will either be adopting, progressing, or seriously considering ecocide law. What feels hopeful is how basic and common-sense the principle is. Some people say ecocide law is a response to the climate and ecological crisis; we tend to see it the other way around. The crisis exists because this law was not established 50 years ago. Ecocide law is a foundational piece that should always have been there, and now is simply the time to put it in place.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Interview conducted by Celine Teunissen.

. . .

Jojo Mehta is the Co-Founder and CEO of Stop Ecocide International, an initiative working to establish ecocide as an international crime. She is Chair of the Stop Ecocide Foundation and convener of the Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide, whose 2021 definition has informed legal and policy developments worldwide. A graduate of Oxford and London universities, Mehta has contributed to UN conferences, diplomatic forums, and international media, including TIME, The Guardian, and The New York Times.

Image Credit: © Vyacheslav Argenberg / http://www.vascoplanet.com/, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Recommended Articles

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

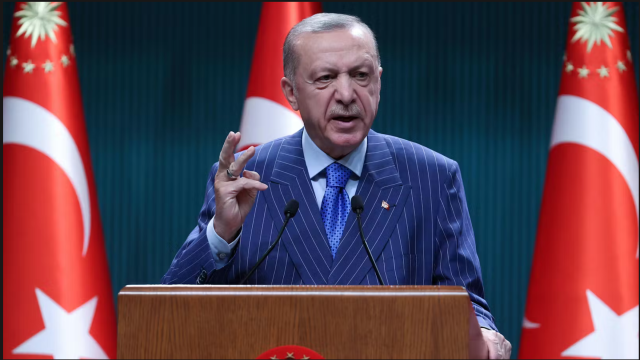

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…