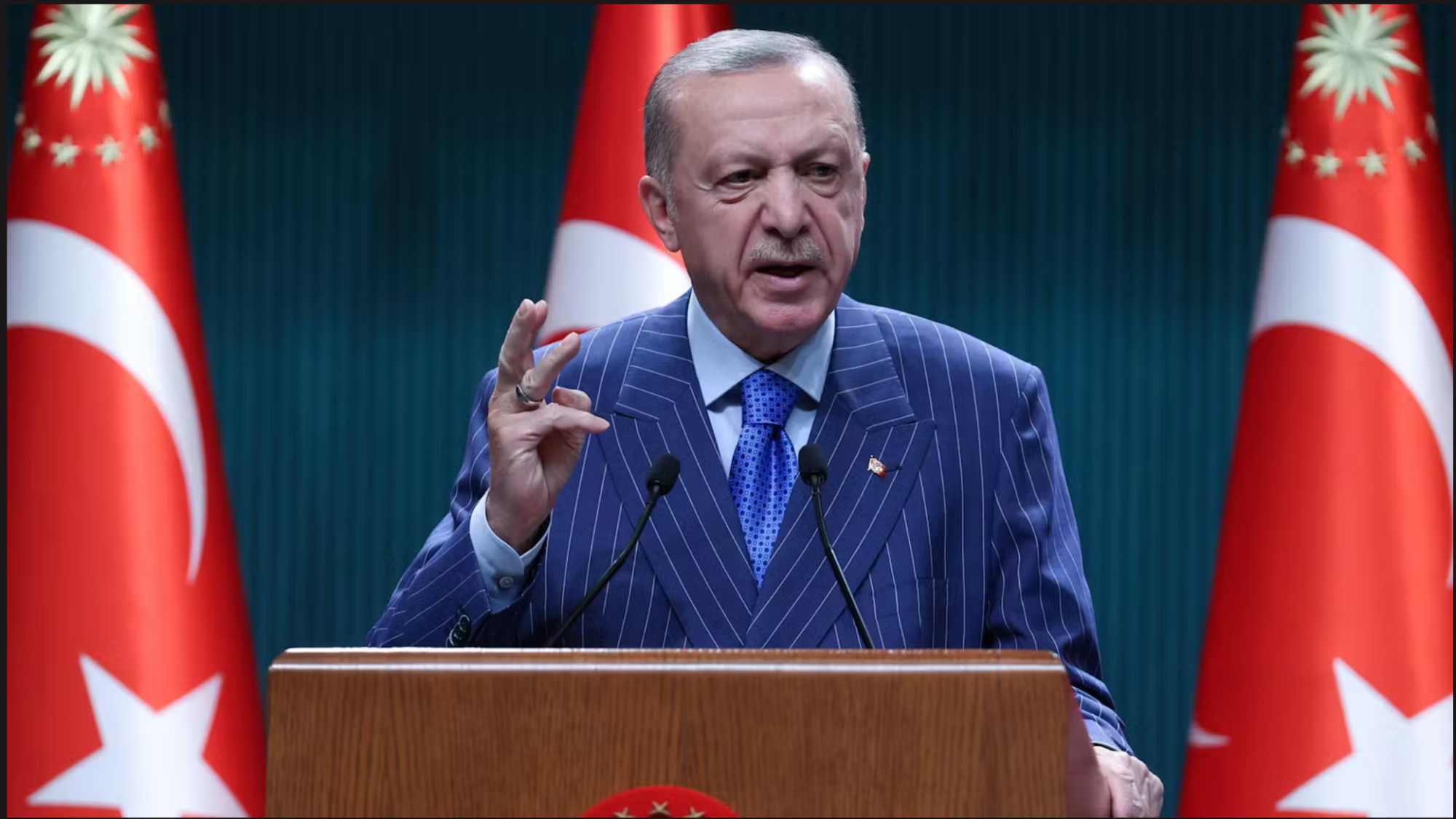

Title: How Erdoğan Has Maintained His Hold on Türkiye

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and emblematic of corruption under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Six months later, the political landscape remains at an uneasy impasse: in November, İmamoğlu was charged with 142 corruption offences and up to two thousand years of jail time. In this interview, Henri J. Barkey, Adjunct Senior Fellow for Middle East Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, reflects on Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian regime and assesses whether Türkiye’s fragmented opposition can mount a credible challenge to his power.

GJIA: In your opinion, what political conditions contributed to the arrest of former Mayor of Istanbul Ekrem İmamoğlu and the subsequent mass protests in March 2025?

Henri J. Barkey: There were no political conditions except that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s popularity had declined very significantly, and İmamoğlu emerged as the uncontested challenger. It is clear that if free elections were held in Türkiye today, İmamoğlu would steamroll somebody like Erdoğan despite his 23 years of continuous, unchallenged power. For somebody who is 33 years old in Türkiye, all they have ever known is Erdoğan. Even if people genuinely like a leader, there is a degree of fatigue with the same leader, and the population will naturally be tempted by change. In this particular case, İmamoğlu represents a new vision, a new set of ideas, and most importantly, a new face.

In March 2025, Erdoğan realized that İmamoğlu would defeat him in a future contest. Not one prone to take chances, Erdoğan decided to lay the groundwork to eliminate İmamoğlu by ordering the judicial system he totally controls to manufacture charges and accusations. Nothing was left to chance; the most absurd was a post-facto technicality: when İmamoğlu transferred from one university to another 33 years ago, Erdoğan’s henchmen incorrectly claimed he had lacked the “proper” paperwork, and therefore, his undergraduate degree was deemed to be invalid. The Turkish Constitution requires a presidential candidate to have an undergraduate degree. Overnight, İmamoğlu’s potential candidacy was voided. This was the most farcical charge, but they piled on hundreds of others to ensure he remains in jail for a very long time.

GJIA: Despite facing this extreme public backlash and continued opposition, how has President Erdoğan maintained political authority since 2014?

HB: Erdoğan came to power because he opened the economy and the political system, but also because he embraced democracy. He did all the right things for one and only one purpose: to protect himself from the Turkish military. Until 2010, the Turkish military was the single most powerful force in Turkish politics. But the generals made a strategic error in 2007. They tried to block the election of one of Erdoğan’s closest confidants to the presidency. What did Erdoğan do? He called national elections, the Justice and Development (AK) Party won with an overwhelming majority, and it was the defeat of the military. With the military out of the way, Erdoğan emerged as the uncontested leader.

Additionally, the Turkish press is completely controlled. No one dares to write independently because they can be prosecuted for the most unbelievable things. The prisons are full of journalists who have been arrested. İmamoğlu, for example, has been in jail for six months and hasn’t been prosecuted yet (as of October 2025) because once they throw you in jail, that is it. Eventually, they will find you guilty of something in order to keep you there. There are some very well-respected journalists who find themselves in jail now. In Türkiye, the rule of law is just the arbitrary implementation of Erdoğan’s wishes.

GJIA: Looking back over the past eight months (from February to October 2025), what have challenges from the opposition looked like, and why have they not been successful?

HB: It is a little bit like the problem Democrats have in the United States: if you cannot control the parliament, how are you going to challenge the government? All you can do is go out on the streets and make sure that people are aware of the failures of the government. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the previous leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), ran against Erdoğan and lost because he did not excite people and did not run the party well either. Until this new leadership came to power, the opposition had been rather meek, unimaginative, and stuck repeating the same unsuccessful discourse over and over. Now, however, it is very clear that if the candidate for the presidency were İmamoğlu, the opposition party would win.

GJIA: How has the Kurdistan Workers’ Party’s (PKK) recent decision to withdraw and renounce armed conflict affected Türkiye’s domestic political climate? Does this development meaningfully advance prospects for a sustainable resolution to the Kurdish question?

HB: I think it was a Kurdish member of parliament who said, “You can’t have democracy in Diyarbakir and fascism in Istanbul.” That is to say, the Kurds have always wanted democracy, the ability to express their culture and use their own language, and to be recognized as Kurds. When Erdoğan came to power, he hinted that he was interested in a solution to the Kurdish problem. But the political leader of the Kurds, Selahattin Demirtaş, one of the brightest, most democratically minded people I know in Türkiye, and a possible solution to the Kurdish problem, has been in jail for almost ten years. For Erdoğan, it is personal. Demirtaş is in jail not because he committed any crimes, but because he successfully stood up to Erdoğan. Resolving the Kurdish question requires a political system willing to make concessions and become inclusive. Erdoğan does not believe in any of these.

The Kurdish question is not a military problem; it is a political one. The PKK has been militarily defeated; it may have one significant mountain hideout in Iraq, but the Turks have 158 bases that completely encircle it. The Kurds in Türkiye have two demands: democracy for themselves and recognition of the Kurdish entity in Syria. It is hard to see Erdoğan agreeing to either of these, hence a solution is unlikely. The PKK has finally adopted a smarter political strategy. To date, the concessions they have offered have not been reciprocated. The current negotiations are more about Erdoğan wanting to somehow neutralize the Kurdish vote in Türkiye. It remains to be seen if he is going to be successful; he will call for new elections if he manages to reduce the opposition to him among the Kurds through these concessions on the peace process. He needs to neutralize part of the Kurdish vote, and his participation in the peace process is all about that.

GJIA: What are the broader implications of Türkiye’s democratic backsliding and how should the international community respond?

HB: Türkiye’s backsliding has been going on for a very long time now. The United States used to closely watch Turkish domestic politics, and even Erdoğan had to be very careful in how far his government could go in terms of domestic repression. Today, unfortunately, the U.S. government has essentially decided that Erdoğan can do whatever he wants. Trump likes him because he’s a “tough guy,” but it is not just Türkiye; it is writ large everywhere. American criticism used to be the most important influence on Turkish behavior. I remember participating in human rights reports—we took them very seriously. That tradition continued until Trump came to power.

Europeans have been critical, but they need Türkiye to limit immigration because many migrants to Europe come through Türkiye. Additionally, Türkiye’s misbehavior serves Europe because many Europeans do not want Turks in the European Union—they see their presence as politically overwhelming the continent. So, I would argue that Turkish authoritarianism paradoxically serves the Europeans, because it gives them reasons not to integrate Türkiye.

What is interesting is that when Erdoğan came to power in 2003, Europe was genuinely optimistic. Only in the far future from now do I see the situation changing. There will have to be reforms in Türkiye, and the international community will have to be convinced, because clearly the supposed reforms from 2003 turned out not to be worth the paper they were written on.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Interview conducted by Chloe Taft.

. . .

Henri J. Barkey currently serves as the Bernard L. and Bertha F. Cohen Chair in International Relations at Lehigh University and on the Council on Foreign Relations as an adjunct senior fellow for Middle East studies. He has previous experience as the Director of the Middle East Center at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars and Chair of the Department of International Relations at Lehigh University. He also served on the State Department Policy Planning Staff from 1998 to 2000. Professor Barkey has written extensively on issues in the Middle East and Türkiye.

Image Credit: Adem Altan, CC BY 4.0, via Heute.at

Recommended Articles

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In this interview, GJIA sits down with Jojo Mehta, Co-Founder and Chief Executive of Stop Ecocide International, to discuss the global movement to codify ecocide as an international…