Title: The Cruise Industry: An Insight into International Tourism in the Face of Global Fragmentation

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand passengers and landmark amenities. This comes despite a tumultuous period in global politics and relationships, to which the travel industry is uniquely exposed due to its transnational operations. In this conversation with GJIA, Clinical Professor and Naval Commander (Retd.) Andrew Coggins, with over 20 years’ experience researching cruise lines, explains their unique approach to international laws and security, and suggests what international tourism can learn from their role over the coming years.

Over the past year, we’ve noticed a rise in global tensions when it comes to international travel, with many countries issuing visa restrictions and charging special taxes. Are there any broad shifts that have stood out to you in particular?

By far, the biggest shift has been the decline in inbound travel to the United States. As a professor in academia, I’ve noticed it firsthand in terms of our decline in foreign students, but it’s also reflective of tourism in general. When people have difficulties getting visas to come to the United States, they go elsewhere; when German tourists on a visa waiver program get caught up in Hawaii by immigration, that creates a negative reputation back in Germany and affects a lot of potential travel we would’ve seen coming from there.

It’s unfortunate because the United States is approaching its 250th anniversary next year, and we really should be seeing a booming year for travel. We’re also meant to host the World Cup, so it’ll be interesting to see what the advance booking figures look like in January for the year. In terms of second-order effects, overseas tourists tend to spend more on a magnitude of 50 to 100 percent, compared to domestic tourists, for the same given location. As a result, we can absolutely expect a lower economic growth figure than we otherwise should have seen.

International institutions like the UN World Tourism Organization and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) are particularly relevant to international travel. Amidst the overall decline in the influence of multilateral organizations, do you see them adapting to this new global reality?

They will have a similar role to play for many years to come, particularly because they work at a government level and are facilitators. Their singular goal is the ease of travel and promoting safety, which is in everyone’s interest. Social media narratives have been a factor in this declining trust you mentioned, but unless we see something like an air crash, organizations like ICAO are going to do just fine without pressure. The institutions are heavily involved in collecting and analyzing data, which is a key resource that both companies and governments rely on for their own projections, so as long as that is the case, I see no concerns for these kinds of multilateral groups.

Your expertise is in the cruise industry, and with cruise lines operating so globally and visibly, would you say they represent the broader travel industry’s overall health?

Cruises are what I call the “last resort of safety.” If security tensions are running higher than usual in a place, people may postpone a land vacation, but if they decide to take a cruise, we find they often stick with it. It’s very much a controlled environment, and travelers know that cruise lines are not going to visit a port that has civil unrest or high crime. So, in that sense, this industry is relatively isolated from some of the pressures that afflict other parts of travel, like airlines or hotels.

When travel is doing well, cruises do well, but when travel is not doing so well, cruises tend to still do alright because passengers know that companies will not send a half-billion-dollar asset into a dangerous situation

International travel has seen a turbulent few years since the pandemic. How has the cruise industry’s recovery looked post-COVID?

The cruise industry is finally looking forward to a very good year. There is a period in the early part of the year called “wave season” when many bookings are made, and projections are showing that there will be a very good “wave season” this year. Travel numbers are finally attaining pre-COVID levels, and it has taken almost six years to get there. Compared to other parts of global travel, the cruise industry took longer to recover because it was more cautious. COVID forced the established lines to take a hard look at their ships, and many older vessels were scrapped or sent into the second-hand market. Rebuilding this capacity with newer ships takes time. Moreover, not all regions have recovered equally. For instance, the Asian market is still down compared to 2019, and this goes for all parts of the industry. There are fewer direct flights to Asian destinations from North America, in part due to airspace restrictions over Siberia after the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Many cruise lines rerouted away from areas like the Red Sea due to operational vulnerability. Do you foresee a broader trend of cruise itineraries becoming less globally ambitious and focusing on “safe” regions?

The Red Sea is an emerging market, with some young Saudi cruise lines, which is why it drew back so fast. The issue with being globally ambitious is that companies have to take a hard look at what their emerging markets really are, and often, there are other reasons why they find it difficult to expand into them. India should be an increasingly popular choice, but due to local laws, only Indian-flagged vessels can sail directly between two Indian ports. Their long coastline means you can’t fit an international stop very easily, so cruise lines just avoid the market altogether, independent of other political concerns.

But remember, cruise lines, like airlines, go where people want to go. You can have all the amenities you want on these new ships and never leave the boat, but people tend to book cruises because they want to go somewhere in particular. That itself is a function of political stability and ease of access. Therefore, a company’s operational department’s first consideration is analyzing where its market is excited to be. There is a very high repeat factor within the cruise industry, where if a given individual takes a cruise, they are almost 95 percent likely to take another one. This is why many cruise lines focus on a set of marquee ports that they know are popular and accessible, while also looking at new destinations reachable from these stable ports to avoid oversaturating their market.

What are the international legal concerns that affect cruise lines’ business more than other kinds of travel?

One really unique concern to keep in mind is this principle of cabotage regulation that I just mentioned. In broad terms, cabotage is the right to transport certain things within a country. The United States is a place that restricts this to U.S.-flagged vessels only. This is why Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) America exists as a separate division of the firm, because if a ship wants to sail around Hawaii, it has to fly the U.S. flag. With fifth freedom rights, airlines don’t really have to deal with this.

Also important to consider is taxation and labor law. This is actually one of their strengths. Cruise lines can—and very much do—register their vessels in places like Liberia or Panama, even if their corporate operations are based out of the United States. Where you register a ship plays a major role in how much of the profit you can bring back to your firm. Additionally, some countries mandate cruise lines to pay subsidies to shipyards or staff their crew to a certain percentage of their nationality. Because cruise lines factor all these laws in, they tend to build very flexible operational models and are thus more resilient than other parts of the tourism industry.

On this topic, many famous destinations like Venice and Alaska have tightened environmental regulation or restricted tourist capacity. Will these pressures reshape which destinations remain viable long-term for cruise tourism?

Look, people will always want to go to Venice. So, for the Venetians, this is a question of “How many visitors do we really want?” One way of answering this is by restricting the days cruise ships can come in. But it is important to remember that in terms of a tourist footprint, Venice deals with not only the cruise passenger, but the ones who come in through land or air. In this equation, cruise lines tend to pay more in fees and taxes to the local government, so I’m confident they will keep their share.

Alaska is a premium destination that is more profitable for cruise lines, so they will keep it viable come what may. Moreover, local towns are also very reliant on income from cruise passengers. Instead of restricting numbers, they are focusing on regulating the type of fuel cruise ships use. There is a limit on the amount of sulfide that can be emitted, which requires cruise ships to burn a higher quality of fuel at a higher price. To counter this, local ports are increasingly offering onshore power to docked vessels, so they aren’t releasing emissions while idle. This has been a partnership between the companies and the ports they visit, and I think is a model for the way they will adapt to future challenges down the road due to their uniquely symbiotic relationship, which hotels and airlines will also begin to consider more and more.

Countries around the world have raised alarms about losing shipbuilding capacity. Do you see this affecting the cruise industry?

Although there has been a rise in the number of Chinese shipyards and a decline in U.S. ones, the center for building cruise ships continues to be Europe. It has been that way for a while, because not only because of the shipyards there, but also because the secondary industries like infrastructure and technology. Unlike freight, the cruise industry is supply-driven, where a company brings out a new ship and then markets it to fill it. Meanwhile, freight requires there to be demand first to build a ship, which then has a long lifespan. This is why it is important to draw a distinction between the kinds of shipbuilding out there. Just because you have a poor freight or military shipbuilding capacity doesn’t mean you have an equally poor passenger shipbuilding capacity.

Airbus and Boeing can build everything from airplanes to spacecraft, but individual shipyards do not operate at such large scales and are more focused on specific kinds of production. A military shipyard can do maintenance work or renovations for a Carnival ship, but it can’t build one because of how specialized a cruise ship model is. It goes the other way, too, and you must remember that ships are vastly more expensive than aircraft are. European yards do sometimes build cargo ships as well, but it is far cheaper to build the ship in Asia than to waste your limited resources trying to do too much at the same time.

Do you think the cruise model can remain a resilient form of global travel in a more fragmented world, or will the industry need to fundamentally rethink how it operates?

Let’s go back to the value proposition—what a cruise offers. A passenger receives a fantastic leisure and travel opportunity for a reasonable price. It combines the novelty value of flying somewhere with the experience value of a hotel or resort. To add, cruises provide this value in a safe environment. Because of the high cost of building ships, they design routes and experiences so precisely to ensure that, once the ship is finished, they will recoup their investment. This is why startups have a very difficult time breaking into the industry, relative to say, an airline or boutique hotel, and why it is relatively stable.

The only major threat to cruises would be a genuinely global downturn like the COVID pandemic. Because cruise clientele is very diverse, if one part of the world is not doing too well, cruise lines can focus their operations somewhere else without losing their investment. That’s the benefit of having a mobile five-star resort. Even during the pandemic, cruise lines were able to find bridge financing guaranteed against their multi-billion-dollar ships to carry them through, despite all their operations being shut down. Very few cruise lines actually went out of business, so that level of expertise and establishment is still around, which keeps the industry resilient. Changes in international laws may move registrations around here and there, but unless those lucrative global tax gaps completely disappear, the cruise model will be around for a while.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Interview conducted by Sid Mehrotra

…

Dr. Andrew O. Coggins, Jr. is a professor at Pace University and an internationally renowned cruise industry analyst. He is an annual attendee at Seatrade’s Global and Asia/Pacific Cruise Conferences and has spoken at and served as a moderator for numerous past conferences. He has discussed topics ranging from travel and tourism trends to maritime law, the Costa Concordia disaster, and the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean. He is a regular contributor to the New York Times, MSNBC, NPR, Bloomberg, and many other reputable publications and periodicals.

Dr. Coggins is a retired U.S. Navy Commander with 23 years of service on seven ships and various diplomatic and international assignments. He is a 1985 graduate of the German Armed Forces Staff College in Hamburg, Germany. He completed his M.S.M. was completed in 1994 at Boston University Brussels, and earned his PhD. in Hospitality and Tourism Management at Virginia Tech in 2004. His dissertation, “What makes a passenger ship a legend: The future of the concept of legend in the passenger shipping industry,” won the ITB 2006 Science Award for Best International Paper.

Image Credit: Jean Beaufort, CC0 Public Domain, via Public Domain Pictures

Recommended Articles

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

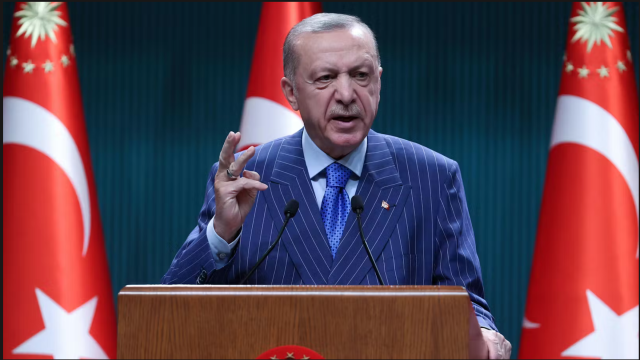

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…

In this interview, GJIA sits down with Jojo Mehta, Co-Founder and Chief Executive of Stop Ecocide International, to discuss the global movement to codify ecocide as an international…