Title: Critical Undersea Infrastructures: A Framework to Address Threats in a Post-Physical Context

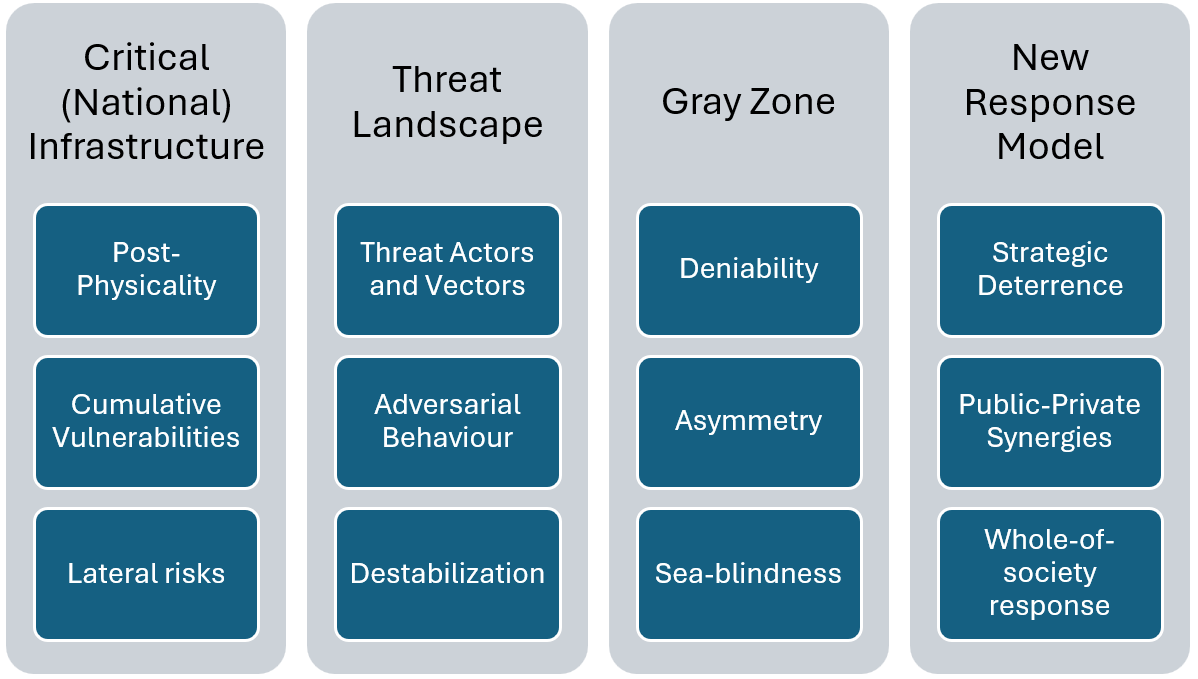

Critical maritime infrastructures (CMI), and in particular undersea communication cables, are increasingly under threat of attacks by malign actors who benefit from asymmetric capabilities and jurisdictional complexities in the maritime “gray zone” to disrupt the flow of data that is critical to economic and national security. Current models of deterrence and governance are structurally inadequate and require a shift from state-centric to multi-stakeholder, post-physical resilience. To that aim, this paper develops a new framework for analysis and policy action centered around three dimensions: first, cables as critical (national) infrastructures, second, the evolving threat landscape, and third, the “gray zone” and questions of deniability and asymmetry. The paper suggests actionable, integrated responses across the spectrum from deterrence and prevention to rapid response and societal resilience.

Introduction

In 2025, undersea cables in the Baltic Sea, Taiwan Strait, and Red Sea were sabotaged or meddled with, disrupting global connectivity. Despite NATO warnings and coast guard interceptions, the international community remains largely powerless to deter these “gray zone” attacks beneath the waves.

Undersea cables are a key component of Critical Maritime Infrastructure (CMI), which also encompasses other vital assets such as pipelines, energy interconnectors, offshore oil platforms, wind farms, ports, and cable landing points. While societal dependence on the free and continuous flow of digital data has increased tremendously, so have vulnerabilities and adversarial behaviors. This is expected to intensify over the coming decades due to escalating geopolitical tensions and new technologies, such as autonomous underwater systems and cyber-offensive capabilities. These technologies introduce new attack vectors and provide malign actors with asymmetric, low-cost tools to interfere with CMI.

Anticipated developments include a rise in cyber-attacks, efforts to intercept data transmissions for future decryption via quantum computing, and targeted attacks on cable landing stations (the weakest points in maritime infrastructure). Additionally, sabotage attempts by non-state actors against submarine cables are likely to become more prevalent. For example, the Houthis have demonstrated an understanding of the strategic advantage gained by destabilizing maritime systems. The convergence of these threats, alongside the fragility of other critical infrastructures (e.g., satellites and energy grids), may significantly undermine future digital resilience and sovereignty. Current models of deterrence and governance are structurally inadequate to protect undersea infrastructure, requiring a shift from state-centric to multi-stakeholder, “post-physical” resilience.

Critical National Infrastructure in a “Post-Physical” Context

Economic prosperity and global security depend on the free and continuous flow of digital data via undersea cables. This dependence is expected to persist over the following decades, primarily because current satellite communication systems lack the capacity to manage the large volumes of data traffic. A substantial reliance on undersea cables entails heightened exposure to both accidental and deliberate disruptions.

Furthermore, digital sovereignty depends on the security of critical undersea infrastructures. However, cables are often distributed far beyond the borders of the origin state—complicating governance, accountability, and policing mechanisms.

A “post-physical” security framework rests on three pillars. First, it recognizes that undersea cables are post-physical systems, exposed to cumulative vulnerabilities and cascading risks. Second, it accounts for an evolving threat landscape with the capacity to disrupt Western societies. Third, it addresses the dynamics of the maritime gray zone, where deniability and asymmetry complicate deterrence. Together, these dimensions support more integrated and actionable responses to threats against CMI.

Figure 1. A multi-level framework for assessing threats to undersea infrastructures and formulating policies

Academic commentators and policymakers have likened undersea cables to critical national infrastructure. This does not account for the multinational, transnational, and global nature of undersea infrastructures. This misconception hampers responses to threats against CMI. For example, international communications via both undersea cables and satellites could be simultaneously disabled. Terrestrial communication systems, whether physical or wireless, are also at risk from sabotage, cyberattacks, or signal jamming. The use of foreign-based data servers further exacerbates these vulnerabilities.

Moreover, specific vulnerabilities associated with undersea cables include lateral risks, such as the impact of extreme weather on cables, landing sites, and the energy infrastructure that supports them. These intersecting risks demonstrate the fragility of digital communication systems and pose significant challenges to the long-term maintenance of digital sovereignty and national security. Preparing for combined and cumulative disruptions requires a whole-of-society approach to security, whereby citizens, economic actors, and governments work together to prepare for and address crises. Thus, it is urgent to conceptualize undersea cables not as a critical national infrastructure but rather as a critical international, transnational, and post-physical infrastructure that requires new and innovative models of governance.

An Evolving Threat Landscape

CMI includes physical assets, transmitted data, and cyber-physical systems, making it vulnerable to both kinetic and cyber-attacks. Threats range from espionage—such as tapping communications or mapping undersea networks—to sabotage of cables and landing points, as well as hybrid operations aimed at destabilizing societies.

Recent incidents in the Baltic Sea and in the Red Sea have shown that malign actors increasingly exploit the opacity of the maritime domain to conduct disruptive activities and hamper Western resilience under the sea while maintaining plausible deniability. These cases exposed systemic weaknesses in surveillance, coordination, and crisis response, particularly when infrastructure spans multiple jurisdictions and ownership structures. They highlight why a shift toward multi-stakeholder, post-physical resilience is no longer optional but necessary.

Malign actors can be divided into two overlapping categories: those driven by ideological, political, or geopolitical motives (such as states, their proxies, and terrorist groups) and those primarily motivated by financial gain (usually criminal organizations). But in many cases, criminal networks operate on behalf of state actors. A well-documented example is the so-called “shadow fleet,” where malign actors register their vessels in countries with lax regulations, low taxes, and minimal oversight to bypass restrictions and destabilize CMI more easily. Many “flag states” often lack either the capacity or the political will to effectively monitor their vessels.

Furthermore, it is essential to consider lateral risks to critical maritime infrastructure that do not originate in adversarial behaviors: accidents (e.g., damages by fishing equipment or dragged boat anchors), extreme weather, technology failures, or a combination of these events.

The threat landscape for undersea cables is multi-angle, involving a broad spectrum of adversarial behavior and diverse threat actors whose common aim is to destabilize Western societies. Rather than simply interrupting data flow, these operations seek to disrupt normality, spread fear, and undermine coherent responses to external shocks and emerging threats.

The Gray Zone

The concept of the “gray zone” is not tied to any specific geography but rather represents a functional space situated between peace and war. Within this zone, legal jurisdictions are often ambiguous, contested, or unregulated, and responsibilities and accountability are unclear. This ambiguity facilitates activities that are difficult to attribute, giving malign actors plausible deniability and making the gray zone particularly conducive to sub-threshold operations (actions designed to cause damage or disruption but not start armed conflict).

Despite its importance for security and prosperity, policymakers still lack an understanding of the specificities of the maritime domain that make it particularly well-suited to gray-zone activities. Its vastness, overlapping jurisdictions, and the complex web of transnational maritime operations (where vessels may be registered under one flag, owned by entities in another country, and crewed by nationals from yet another) make oversight and enforcement challenging. Furthermore, international law does not explicitly prohibit military activities in Exclusive Economic Zones, giving malign actors the physical space they need to carry out attacks.

In addition to being vulnerable to gray-zone tactics, critical maritime infrastructure suffers from governance limitations stemming from the private and multinational ownership of undersea cables. This results in “digital un-sovereignty,” where a society or government does not have full control over its digital infrastructure.

These physical, legal, and political factors complicate both national and international oversight of CMI and hinder effective intervention. This further allows malign activities to be conducted with minimal risk of attribution or accountability. Additionally, malign actors have a comparative advantage in conducting sub-threshold activities in the gray zone since the financial and political costs of attacking undersea infrastructure are lower than the cost of deterrence and responding to attacks.

The pervasive “sea-blindness” of policymakers has so far hindered an appropriate risk assessment of CMI and has misguidedly geared responses towards terrestrial mechanisms, such as surveillance and policing.

What Should Be Done?

Immediately, governments must apply strategic deterrence. The goal of threat actors is not limited to disrupting data flows—the threat also encompasses destabilizing Western societies. Thus, states must adopt a broad posture to prevent a wide range of adversarial behaviors across domains. Effective strategic deterrence requires limiting plausible deniability through rapid response and credible identification as well as attribution of threat actors by coastal states’ law enforcement agencies and NATO or EU multinational naval task groups. Publicly denouncing perpetrators through diplomatic channels reinforces accountability.

Structurally, strengthening private sector accountability and addressing post-physicality would build resilience. Cable operators should enhance resistance and resilience by deepening cable placement, diversifying routes, implementing network redundancy, deploying decoys and technical defenses against autonomous systems, and separating energy and communication cables.

In terms of addressing post-physicality, undersea cables cannot be reduced to critical national infrastructure. They are part of an international and transnational network of assets, stakeholders, data, and interests. Responses must adapt to a post-physical domain with blurred ownership and jurisdiction by building strong public-private partnerships, modeled on the close alignment between states and shipping companies such as Denmark and Maersk, and increasingly reflected in regional undersea cable consortia involving major technology companies and telecom operators.

Normatively, so long as policymakers overlook the limitations inherent to the maritime domain, response mechanisms lack the flexibility to tackle threats in the maritime gray zone. Enhanced Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) enables early threat detection and real-time monitoring. Proactive tracking of suspicious civilian vessels is vital, especially in gray zone scenarios where plausible deniability is a strategic asset.

To counter sub-threshold threats, clear protocols for responding to espionage, erratic ship behavior, and sabotage, both in real time and post-incident, should be established at state level. At the international level, legal reforms must address gaps around opaque jurisdictions and open registries, while sanctions should target non-compliant private actors.

A comprehensive strategy must also involve state institutions, international bodies, private actors, and local communities. Public awareness is crucial, including contingency planning for simultaneous cable and satellite disruptions, e.g., sovereign backup payment systems and cash reserves. These recommendations, if implemented, should eventually lower the vulnerability of CMI.

. . .

Basil Germond is Professor of International Security at Lancaster University, United Kingdom, and is Co-Director of the University’s research institute, Security Lancaster. His research focuses on maritime security, sea power, the maritime threat landscape, and the strategic governance of ocean spaces. He has published extensively in leading peer-reviewed journals and regularly contributes to academic and policy debates on international security and maritime strategy.

Image Credit: Undersea cable reels by David Martin, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Recommended Articles

This article explores how the Palestinian crisis and the death of the two-state solution endangers the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. It illuminates the complicated relationship between Jordan, Israel, and Palestine…

This article explores the uncertain future of Arctic governance amid shifting global geopolitics. It argues that whether Washington and Moscow opt for confrontation or cooperation, multilateralism in the Arctic…

Twenty-five years ago, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, establishing a framework that underpins the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Agenda. The Resolution recognized both the…