Title: Wukan Village, China: A Narrow Path for Local Democracy

On March 1 2012, the villagers of Wukan (13,000 inhabitants), in Southern China’s Guangdong province, will elect their village representatives under the supervision of a self-chosen committee. This unique case of village democracy is the result of almost a year of demonstrations protesting massive land grabs by local officials. Over 75 percent of the village’s arable land, worth millions of dollars, was sold to developers, leaving many peasants without resources or adequate compensations.

The situation escalated on December 11th as Xue Jinbo, one of the protesters’ leaders, died in custody, which triggered large-scale demonstrations and destruction at local government offices. The nine members of the village committee fled, leaving the village in a situation of de facto autonomy. After ten days of a quasi-siege situation, provincial authorities stepped in to end the crisis, finally granting what was considered a victory for the villagers: the suspension of real-estate development projects, the promise of an investigation of the death of Xue Jinbo (and the release of other detained leaders) and a commitment to run free elections.

As of today, it is not clear how the land issue will eventually be solved and Xue Jinbo’s body has not been released (it probably holds evidence of beating or torture). However on February 1st the villagers selected the committee that will organize March 1st elections, in what was Wukan’s first transparent vote in decades.

This outcome is all the more important as Wukan is but one of tens of thousands of “mass incidents” each year in China, a large proportion of which occur over illegal land seizures. Some think that it might pave the way for future reforms of local democracy in the whole country. However, despite an undeniable political breakthrough, the democratic outcomes of these events remain extremely uncertain.

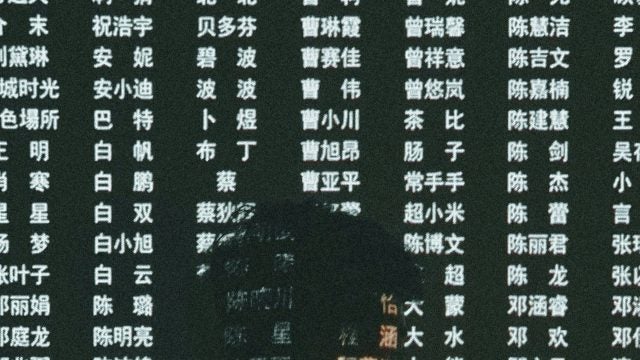

Wukan village has proven wrong the assumption that the Chinese may not be “ready for democracy.” The journalists and activists who snuck into the village during the 10-day siege all underlined the villagers’ discipline and militant efficiency. As soon as the Party officials had left, the villagers designated a temporary committee. They organized regular mass rallies and created outstanding protest signs and banners. They were particularly skillful at developing a sophisticated communication strategy, which ranged from providing food and information to journalists to posting videos of police violence online. They fooled online censorship by changing keywords in their tweets about Wukan events. Most importantly, they paid great attention not to frame their demands as a protest against the Communist Party, but as a local, ad hoc claim for justice, despite the hopes of activists and dissidents who encouraged them to point at more general, systemic causes of local corruption.

This careful framing is probably one of the reasons for the relatively “peaceful” success of their mobilization, as it enabled the villagers of Wukan to preserve an upper hand in negotiation with the provincial authorities. The leaders of the protest consistently stated their support of the Communist Party and their “satisfaction” with the response of the provincial government. However it also underlines the capacity of the regime to channel even the strongest contestation so that it does not question the ruling of the Community Party.

Indeed some details suggest that not everything has changed in Wukan as the authorities are using very classic strategies to keep the situation under control. The late acknowledgment of the villagers’ claims by the provincial Party secretary corresponds to a relatively ordinary scheme in which local authorities are blamed for not paying attention to the interests of the people, whereas the provincial and central authorities are portrayed as being more responsive and accountable. Besides, the charges against three of the leaders of the protests were not dropped as promised, while Lin Zuluan, the head of the temporary committee chosen by the villagers, was designated in January as the local Party secretary. As often, co-optation on the one side and threat on the other side are used to neutralize and divide potential opponents.

The villagers of Wukan are determined to make these elections a success and a starting point for further democratic changes. They are also well aware of the pressures and conflicts that are taking place right now. The path is indeed very narrow.

. . .

Severine Arsene, Ph.D, is the Yahoo! Fellow in residence at the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University. With a focus on China, her current research focuses on Internet governance and online protests.

Image Credit: Kc1446 at Chinese Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

Recommended Articles

Despite the non-political positioning of its organizing body, the European Broadcasting Union, the Eurovision Song Contest plays an important role in shaping how the public imagines and understands ideas of…

Inuit across the Arctic have long witnessed dramatic environmental changes in their homelands. Their observations, deeply embedded in their relationship with the land and water, offer critical insights…

This article discusses gender trolling in China’s media culture, exploring the tension between feminist activism, digital platforms, and state ideologies. It highlights how the growing digital manosphere and exclusionary feminist…