Title: From Tehran to Khartoum: Thirty-Five Years As An American Diplomat Interview with Ambassador Joseph D. Stafford III

Click here to view as PDF || Shop the Entire Current Issue- The Integration of Regions || Return to The Integration of Regions index

“I know it is an important challenge for U.S. foreign policy…to press the Iranian gov- ernment for responsible behavior on issues…” “I think it is important in Sudan, as elsewhere in the region, to impress upon the government and public that we are aligned with the forces of reform, but that we recognize the process of democratic transitions can be a difficult one…” “Our fundamental objective remains to promote the emergence of a Sudan that is at peace internally and with its neighbors…”GJIA: What has been your favorite part about being a career Foreign Service Officer, and why?

Stafford: I think my favorite part has been having the opportunity to live and work overseas, in other cultures, and to work on issues of importance to the United States and our international relations. The assignments in Washington have also been interesting but, in my mind, the most stimulating and enjoyable part of my Foreign Service career has been the chance to work overseas and meet ordinary citizens and members of civil society across the world, and to represent the US government.

GJIA: During your first tour, you were forced to flee the embassy in Tehran while it was under siege. How did that experience influence your career in the State Department?

Stafford: That was certainly a stimulating first tour. In a number of ways it reinforced my interest in the Foreign Service. I realize my wife and I were very lucky to be able to seek refuge with the Canadians, and then leave surreptitiously and avoid being taken hostage. I would say on balance, recognizing that it was not a typical first tour in the Foreign Service, that nonetheless, in a way, it only heightened my interest in continuing that type of career. We also had the opportunity a couple months before the assault on the embassy to travel around Iran a little bit, and we inter- acted with Iranians on a daily basis on the visa line. Those experiences were formative for me, and they only furthered my desire to be a Foreign Service Officer.

GJIA: What was your first reaction when you found out that Ben Affleck was making Argo, a film about your experience during the hostage crisis? How did you feel about having such a deeply personal and terrifying experience relived in the public spotlight?

Stafford: I have to tell you, I was sort of bemused. It was not the first film that had been made. A Canadian outfit had done some sort of film a year or two after the event, and there had been a couple of books. I guess I was sort of bemused. I viewed it that way. For me it was an experience that happened a long time ago. Memories of it for me—to tell you the truth—have faded. I do appreciate the fact that the film has served to highlight, in a positive way, the role of the U.S. Foreign Service, the CIA and, of course, the important, vital role of the Canadian government, to whom we are eternally grateful. That is my take on it. I hope to see the film myself someday. My wife has seen it and she says my character comes off well.

GJIA: What are your impressions of Iran today, and what do you think the future holds for U.S. engagement with the Iranian government?

Stafford: I have not, to tell you the truth, followed events in Iran very closely in recent years. I recognize what an important country it is, and I certainly hope that there will be a change in the Iranian government’s behavior and that we can find a modus vivendi in the form of normalized relations someday. Iran is a large, strategically located country. It has a rich culture, rich history—a mosaic of cultures, peoples, and languages, really. I know it is an important challenge for U.S. foreign policy, and I’d say for the international community generally, to press the Iranian government for responsible behavior on issues ranging from developing nuclear capabilities, to combating terrorism, to promoting peace, stability, and democracy in the Middle East. It is obviously quite a tough endeavor, but I recognize that we have to keep at it, in the hopes that someday Iran can regain a respectable place in the international community.

GJIA: As an expert on the Middle East, and as an Arabic speaker, what do you envision for the future of U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East and North Africa? Who will be our key allies? And what will be the key challenges for policymakers?

Stafford: I have spent some time in the Middle East, and I have been in North Africa in recent years. I would say, of course, the fundamental issues of Arab-Israeli peace, in particularly Israeli-Palestinian peace are extremely pressing. We must do everything we can to encourage the parties to move forward constructively. The establishment of a viable Palestinian state is part of that process, but also the normalization of the Arab-Israeli relationship needs to be considered, more generally. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, there is a need to be as supportive as we can be in every way of the processes of reform and development underway in the Middle East. It is important to bolster the forces of moderation, and those forces, in general, seeking peace, modernization, and development. It is also important that we work to isolate extremist forces in cooperation with our moderate Arab friends in the region, within the greater context of combating global terrorism.

We also have an ongoing challenge of impressing upon Muslims—and people in the Middle East are obviously a key element of the Muslim world—that the United States has a deep respect for Islam, and that we as a nation do not equate Islam with terrorism, death, or destruction. On the contrary, Islam has noble teachings and those that resort to violence under the guise of Islam are distorting it. In any case, I’m confident that we will remain deeply engaged in the Middle East. We have compelling reasons for doing so.

GJIA: In the wake of the Arab Spring and continued violence in Syria and Egypt, what role should the international community play (if any) in helping to shape new democracies?

Stafford: I think that it’s important, in engagements with leaders of the Arab Spring states, to make clear that we support the development of democratic institutions. It’s also important to conduct vigorous outreach efforts with civil society, and with forces for reform, democratization, and political openness. We must also make clear our opposition to violent extremism.

In Syria, of course, the ongoing horrific violence is a reminder that regimes that steadfastly reject the forces of change and reform and resort to such brutal repression cause tremendous damage to their countries. The ongoing death and destruction we are witnessing in Syria is so regrettable.

We have to continue our efforts on different fronts and respond to the situation in Syria as we have been doing. Doing our best to mobilize the international community, working with key friends and allies, and helping to shape an international consensus to pressure the Bashar al-Assad regime to make way for the forces of democracy, reform, and change in Syria.

GJIA: September 2012 saw increased protests at Western embassies across the Middle East and North Africa, and the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum was certainly not immune to this trend. What challenges do you envision the United States having to contend with as a result of the Arab Spring movement?

Stafford: I think it is important in Sudan, as elsewhere in the region, to impress upon the government and public that we are aligned with the forces of reform, but that we recognize the process of democratic transitions can be a difficult one. When one considers the experience of the United States, with the decades and decades, or really centuries, that it took for our democratic experiment, including a bloody civil war, it puts things in perspective. So our effort needs to be one of patient work with the governments in question, while also making full use of the diplomatic and public outreach tools at our disposal, such as official dialogue, economic cooperation, and humanitarian assistance. In the case of Sudan, for example, we are providing a considerable amount of humanitarian assistance in the conflict areas—first and foremost to Darfur, but also in the southern part of Sudan, where conflict continues to rage. Beyond those more critical, lifesaving efforts, our dialogue with and outreach to pro-democracy activists, our civic education work with political parties, our efforts to strengthen election commissions and to enable them to conduct free, fair, and transparent elections, are all key ways that American engagement can help during this critical transition period.

Additionally, beyond official economic assistance, I believe that private commercial cooperation with these countries is very important, not just for the trade, investment, and economic benefits, but also in the sense that people in these countries gain exposure to U.S. companies that operate and respect the democratic values and the rule of law. This is also good experience for U.S. companies. Unfortunately, in the case of Sudan, this type of interaction does not really occur due to the array of sanctions over the years that the U.S. government has imposed upon Sudan, for various reasons, including the issue of genocide in Darfur and the ongoing violence there going back years, previous associations with terrorist elements, and the latest violence that erupted over a year ago in the southern part of Sudan following the secession of South Sudan. So we have some special challenges in the case of Sudan, but I would still say that it is important to draw upon the wide array of tools in promoting peaceful change and reform, as well as development.

GJIA: You arrived in Sudan under difficult political conditions: Sudan is fighting rebel movements and political unrest in the West, South, and East, including a deadly campaign against both rebels and civilians in the Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile; Sudan and South Sudan still have not fully implemented aspects of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended decades of bloody civil war; the oil life- line that both countries depend upon was shut off due to disputes and both countries now face grave economic crises; and for a moment, the armed forces of both countries looked to be on the path back to full-scale war, with northern warplanes bombing southern territory and southern troops seizing the northern oil field of Heglig. As a career diplomat who certainly has not shied away from countries with seemingly intractable political rows, what hope do you see on the horizon for the two Sudans, and for the U.S. relationship with the Khartoum government?

Stafford: In terms of the relationship between Sudan and South Sudan, I think that we need to continue our robust support of the African Union mediators’ efforts to get the two countries to move forward on the cooperation agreements that they’ve signed in September 2012. The process has already been delayed far too long in the actual implementation, so that has to be a key focus with the ultimate aim of securing a renewed sense of good- will and commitment on both sides in implementing those agreements. Now, I think that both sides recognize that a return to war has to be avoided at all costs, that the vital interests of the two peoples are at stake and so it’s vital that they implement the security arrangements they agreed upon last September, and, particularly the agreements to resume oil flow and to open up the border for badly needed trade between the two countries. These things are essential for the two countries’ development, and for the hopes of improved standards of living for the people. Those considerations must be paramount in the minds of the two leaders and their two governments. So I am cautiously optimistic that we will see progress, simply because the two parties will realize that there is no alternative or that the alternatives are unacceptable; war, a status quo of tension, of a frozen relationship in a certain sense, and closed borders are not viable for either country in terms of coming to grips with the challenges each faces. So, the bottom line is that both sides recognize that a return to war must be avoided, and that we will see progress in implementation, delayed as it has been, of the cooperation agreements.

On the U.S. relationship with Khartoum, I think the key there is to look for opportunities—and encourage the government of Sudan to look as well— for the expansion of our dialogue and our search for ways to deal with these fundamental issues of peace and stability, democracy, good governance, and development for Sudan. Our fundamental objective remains to pro- mote the emergence of a Sudan that is at peace internally and with its neighbors, particularly with South Sudan. So we need to continue finding ways to expand that dialogue and develop that dialogue with the Government of Sudan and encourage responsiveness on the questions of peace that are fundamental in moving forward in the relationship. In that respect, there are many salient issues we hope to address, including: progress in removing sanctions, a process for removing Sudan from the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism, moving forward on the peace process in Darfur, resuming political talks with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North and reaching an agreement on the cessation of hostilities, permitting humanitarian access that has been delayed far too long to displaced persons in the Two Areas, and of course, moving forward with implementation of the cooperation agreements with South Sudan. So that’s quite an agenda, as you can imagine—and governance and respect for human rights will always be a central theme permeating that agenda—but we hope for an expanded, productive dialogue with the Government of Sudan to deal with these challenges, and remove some of the obstacles on the path to normalization and improvement of ties.

Beyond our engagement with the Sudanese government, I also think it is vital to expand our public out- reach and demonstrate to the people of Sudan that we are not hostile toward them, that we are committed to providing close to $300 million a year in humanitarian assistance, as well as some development assistance. So that’s quite an investment we’re making. Our work with members of Sudanese civil society, with political parties, and with the national election commission that we’ve been involved with in the past, will hopefully present a multitude of opportunities for us to engage with the Sudanese during the run-up to national elections in 2015. So we have quite the agenda here in Sudan, an important country and an important relationship for us, as strained as it has been in recent years.

GJIA: You have experience serving in countries that have been sanctioned by the U.S. government and the international community, such as Iran and Sudan (granted, in the case of Iran, sanctions were imposed after you left). Do you think that sanctions are effective instruments in getting a regime to change its behavior?

Stafford: Well, the sanctions need to be, in my view, accompanied by a robust diplomatic process with the international community to ensure that there is, beyond the pressure resulting from sanctions, the diplomatic pressure from the international community in general. It is not a quick or easy process, that of applying pressure on regimes to get them to change policies that the international community finds objectionable, but it is, again, going back to the idea of tools, a tool of diplomacy—the tool of economic pressure embodied in sanctions—while I think that another important part has to be the provision of humanitarian assistance and making every effort to mitigate the impact of sanctions on ordinary citizens because after all, the target is the governments whose behavior we are trying to change through sanctions, through diplomatic pressure. Again, I return to the idea of the patient, hard-slogging efforts of using every available channel to apply pressure on these governments, and sanctions is part of the package, but it’s not the only part. Diplomatic pressure and humanitarian assistance also have to be essential parts of the overall strategy.

Joseph D. Stafford was interviewed by Warren Ryan via telephone on 19 February 2013.

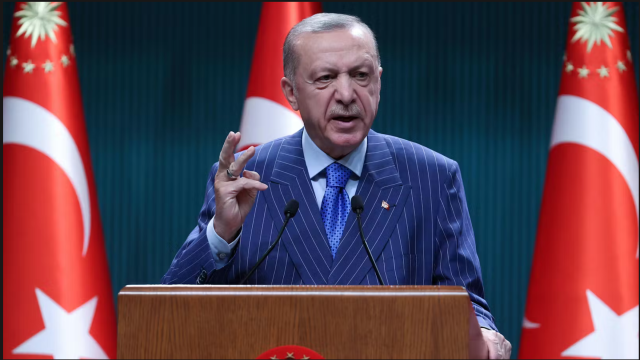

Joseph D. Stafford III is a career Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State, holding the rank of Ambassador. He joined the Foreign Service in 1978, serving his first assignment in Tehran, Iran. Ambassador Stafford and his wife, Kathleen, were among the six diplomats who evaded capture during the Iranian Hostage Crisis, eventually being smuggled out of Iran by the CIA. In June 2012, he was assigned to Khartoum, Sudan as Chargé d’affaires of U.S. Embassy, Khartoum. Image Credit: Don Koralewski, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is an archived article. While every effort is made to conserve hyperlinks and information, GJIA’s archived content sources online content between 2011 – 2019 which may no longer be accessible or correct.

More News

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…