Title: Looking Back to Look Ahead: The Case of US Immigration

Currently, in a US election year, immigration has once again become a hot-button political issue. Candidates must contend with political claims that immigrants are taking Americans’ jobs and disrupting the country’s social fabric. My grandmother, Anna Remmerie, came to the United States in 1921 as a maid. In the 1930s, she returned to Belgium, where I was born.[1] Her experience reflects the history of American immigration and immigrants and discussions about their impact on the US economy. US policymakers cannot lose sight of these economic realities, as they seek to win voters over.

Introduction

The US immigration system currently suffers from immense strain and poor policy. Immigration quotas have been set for countries without considering their size, distance to the United States, or whether they are an ally. The system focuses on family reunification, which disconnects legal migration, to some extent, from the economy’s changing labor needs. Finally, the institutions that administer migration are underfunded and have years-long backlogs. They are overwhelmed, as thousands of immigrants cross the southern border–many seeking asylum. Backlogs invite undocumented overstays.[2] Still, migration reform is unlikely. We are now in an election year, and immigration is central to both presidential campaigns.

Former President Donald Trump’s campaign proposes to heavily restrict immigration. His rhetoric and past policies echo the 1920s and 1930s, during which US policymakers restricted immigration due to immense backlash against immigrants from civil society. Now, in 2024, politicians must avoid repeating these past mistakes, as historically, immigration has driven US economic growth.

Looking Back

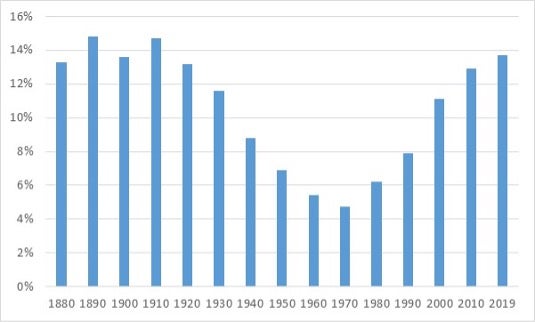

In an environment with few realistic policy options, studying migration and its past offers a helpful perspective. After my grandmother arrived in New York, she circulated in the immigrant communities of the Northeast. She was part of the last wave of European mass migration at a time of unprecedented democratization of long-distance travel, as steamboats shortened transatlantic crossings drastically.[3] As a twenty-one-year-old woman, she left war-devastated Belgium (which had been occupied by Germany during WWI). Millions of men and women had left Europe since the mid-nineteenth century.[4] In the 1920s, around 13 percent of US residents were born outside its borders, which is comparable to today (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1. Percentage of US residents born abroad, 1880–2019

Source: Migration Policy Institute

As a live-in servant, Anna served the wealthy. Census records indicate that her colleagues originated in Germany, France, Belgium, Ireland, and sometimes Canada. In the Northeast, live-in maids for the rich typically hailed from western and northern Europe, although by 1900, 80 percent of all arrivals came from eastern and southern Europe.

The 1920s was The Great Gatsby era, with levels of inequality comparable to today. The United States was a very hierarchical society with rampant anti-immigrant sentiment. The Ku Klux Klan was active in the North, targeting not only Black, Jewish, and Catholic people but also immigrants.[5] Different European nationalities and ethnicities were perceived according to eugenic racial hierarchies. Eastern (Jewish) and southern Europeans suffered the most abuse and discrimination.[6] At the end of the nineteenth century, Italian immigrants were even lynched in Louisiana. Anti-immigrant sentiment had simmered for years, especially in rural areas with the least exposure to immigrants as is also the case today. By the end of the 1920s, the door to America was effectively shut. Drastic migration reductions (by up to 75 percent) took effect, as laws restricted country quotas and limited immigrants. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought migration to a virtual halt.[7]

Presidential candidate Donald Trump has propagated xenophobia, claiming that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country” and coming from “shitholes.” He has also suggested that a second Trump administration would carry out mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, withdraw birthright citizenship, (ideologically) screen immigrants or countries, and reduce legal migration. Trump’s rhetoric echoes the xenophobic rationalization for the restrictive migration laws of my grandmother’s time. Those laws that excluded non-Europeans were justified in part by considering only white Europeans to be truly American (not Native peoples, Black Americans, or descendants from other continents).[8] Before the United States enacts new migration policies, it should consider its own myths about immigrants as well as the extensive research on immigrant integration and migration’s economic impact.

“Immigrants Pulling Themselves Up By Their Bootstraps”

Some 70 million Americans descend from European mass migration.[9] They are a self-evident part of the US fabric despite (past) ethnic differences. The colonies around Detroit where Belgian immigrants used to live have fully assimilated into US society, as have many similar enclaves.[10] Since WWII, the United States has called itself a nation of immigrants.[11]

A selective, romanticized view of European “can-do” immigrants prevails. Past discrimination is often forgotten as is the help European immigrants received. Before WWII, European immigrants in the Northeast relied on local public safety nets. After WWII, they benefited from the Great Society’s federal programs such as unemployment insurance, Social Security, and childcare support.[12] Many organizations provided short-term lodging, opened access to immigrant networks, and assisted immigrants with job searches. Some, like the Belgian Bureau where Anna initially worked, were private initiatives, while others were formally backed by foreign nations. Some European immigrants also came illegally, but former compatriots lobbied to adjust their legal status. White Europeans also benefited from privileged racial positions.[13]

This era of European migration was a massive natural experiment, and only recently have its effects been systematically studied. Researchers at Stanford and Princeton have investigated the integration process using millions of migration and census records. In Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success, Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan summarize these findings and draw parallels to current trends in predominantly non-European migration.

US politicians such as Trump blame immigrants for ongoing national issues. However, studying the ethnicities of migrants’ neighbors, English language acquisition, intermarriages with other communities, and name Americanization, Abramitzky and Boustan find that the pace of twentieth-century European immigrant integration is comparable to that of (non-European) migrants now. All migrant children climb economic ladders and adopt the culture of the new home country more easily than their parents do. This is true today, as it was in the past. Yes, immigrants bring, as Trump put it, “languages into our country that nobody has ever heard of,” but they also master English after only one generation. Even my uneducated grandmother spoke English (in Belgium) until her death.

Looking Forward: The Special Case of Migration

The current backlash against globalization can be rationalized. Unequal access to education and health care, tax evasion by wealthy individuals and multinationals, technological change, and an increasingly global economy have certainly contributed to existing US income inequality. Economists have also documented the adverse effects of international trade on lower-skilled workers in terms of pay and employment, among other factors. It is, however, much more difficult to rationalize the vitriol towards migrants and to pinpoint the negative economic impact of migration, especially in the long run.

Indeed, while economists dislike the current chaos at the border, they see migration predominantly as a source of strength.[14] In aging societies, migration offsets a shrinking workforce and covers the rising costs of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid for the elderly. Migration can also supply much-needed workers in health and social services. It answers the strong labor demand at the lower and higher ends of the skill spectrum. It delivers low-skilled workers in construction, food preparation, and cleaning services as well as seasonal labor in agriculture. At the higher end, new arrivals, including my students, deliver human capital for high-tech industries and universities. Immigrants are more likely to be scientists and entrepreneurs and have won over a third of the US Nobel Prizes in the last thirty years. Immigrants tend to be more entrepreneurial, mobile, and high-skilled relative to the rest of the population in their origin countries.

Any downward wage pressure due to immigration is short term and limited. The skills of immigrants do not always compete directly with those of domestic residents and may actually complement them. Low-skilled migrants often accept jobs domestic workers do not desire such as manual harvesting roles in agriculture. Additionally, no evidence suggests that migrants are a net fiscal cost, especially when tax contributions and benefits are weighed over the entire lifecycle of their stay. In short, it is difficult to make the case against immigration from a purely economic point of view.

In short, migration is a legitimate topic of political debate; a nation’s migration laws should reflect society’s consensus. However, the history of European migration to the United States is relevant for that discussion. Migration reform must balance culture wars with pragmatic, unromanticized, fact-based accounts of migration. The integration of immigrants has never come easily. We must invest in immigrants and their children, as they quickly connect with and improve their new home country.

. . .

I (Professor Peter Debaere) am an immigrant and an economics professor at the University of Virginia, a top US business school. Roughly one-third of my MBA students are immigrants, and many of my colleagues were born abroad. My students with non-US passports report increasing difficulties in getting US companies to sponsor their visas and green cards. Recently, an Asian colleague of mine was confronted at a gas station by someone urging him to go back to where he came from.

In my courses, we analyze the current backlash against globalization. We relate it to the aftermath of economic downturns (the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic) and to inequality. As such, we do not expect the anti-globalization wave to disappear soon. We also discuss the United States’ inflexible immigration system, which defies economic forces and invites illegal immigration.

My brother and I wrote a book about our grandmother’s life, To America and Back Again (in Flemish, Naar Jouw Amerika en Terug). The work offers a lens into the immigrant experience and evokes parallels with our current predicament.

. . .

[1] Anna Remmerie’s migration story was published in Belgium, drawing on her personal correspondence, photos and documents, as well as the academic migration literature in economics and history. Debaere, P. and S. Debaere, 2022, Naar Jouw Amerika en terug. Een brief voor Anna, Pelckmans, Antwerpen.

[2] The Immigration Policy Institute discusses all aspects of the current U.S. migration system. This article draws on among others,: Muzaffar Chishti, Faye Hipsman, and Isabel Ball, “Fifty Years On, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Continues to Reshape the United States,” Migration Information Source, Migration Policy Institute, October 15, 2015. Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, and Doris Meissner, “Rethinking the U.S. Legal Immigration System: A Policy Road Map,” Migration Policy Institute policy brief, May 2021 Cecilia Esterline and Jeanne Batalova, Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States, Migration Policy Institute, March 17, 2022. See also, “How the United States Immigration System Works,” Fact Sheet, American Immigration Council, September 14, 2021 See also, Debaere, P., 2023, “U.S. Migration in 4 Acts,” Darden Business Publishing, UVA GEM 214.

[3] Feys, T., 2013, Transatlantic migration at full steam ahead : a flourishing and well-oiled multinational enterprise, in : Beelaert, B. (red.), Red Star Line Antwerp, p 32-44.Thomas Verbruggen, ‘The Arrival of Foreign Female Domestic Servants in Antwerp and the Role of Compatriots and Relatives as Intermediaries, 1860–1880’ Gender & History, Vol.31 No.3 October 2019, pp. 584–604

[4] Daniels, R., 2004, Guarding the Golden Door, American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882, Hill and Wang, New York

[5] Gerber, D., 2011, American Immigration: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press p. 37

[6] Molina, N., 2014, How Race Is Made in America : Immigration, Citizenship and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts, University of California, Berkeley.

[7] Key references on U.S. migration and U.S. migration policies from a historical perspective: See Daniels, R., 2004, Guarding the Golden Door, American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882, Hill and Wang, New York and Gerber, D., 2011, American Immigration: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. Historical approach to (European). Migration to the United States: Ngai, M., 2004, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. Zahra, T., 2016, The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World, W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

[8] Daniels, R., 2004, Guarding the Golden Door, American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882, Hill and Wang, New York

[9] Abramitzky, R. en L. Boustan, 2022, Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success, Public Affairs, New York, Chapter 8 , p. 194

[10] Stengers, J. 1978, Emigration et immigration en Belgique aux XIXe et XXe siècles, Koninklijke Academie voor Overzeese Wetenschappen, Brussels

[11] Ngai, 2004, p.XXV.

[12] A thorough discussion of how migrants benefited from social programs and the welfare state is Fox, C., 2012, Three Worlds of Relief, Race Immigration, and the American Welfare State from the Progressive Era to the New Deal, Princeton University Press.

[13] Battisti, D. and D. Kang, 2025, The Hidden Histories of Unauthorized European Immigration to the U.S., University of Illinois Press, forthcoming. Molina, N., 2014, How Race Is Made in America : Immigration, Citizenship and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts, University of California, Berkeley.

[14] This article draws on a large migration literature in economics. For good surveys of scholarly economic analyses of the impact of migration on wages, skills and knowledge creation, fiscal policy, etc. see : Peri, G., 2021, c, Annual Proceedings of the Wealth and Well-Being of Nations, p. 19–50. Clausing, K., 2019, The Progressive Case for Free Trade, Immigration and Global Capital, Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Abramitzky, R. en L. Boustan, 2022, Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success, Public Affairs, New York. Edo, A., L. Ragot, H. Rapaport, S. Sardoschau, A. Steinmayr, and A. Sweetman, 2020, An Introduction to the Economics of Immigration in OECD countries, Canadian Journal of Economics, 53,4.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons