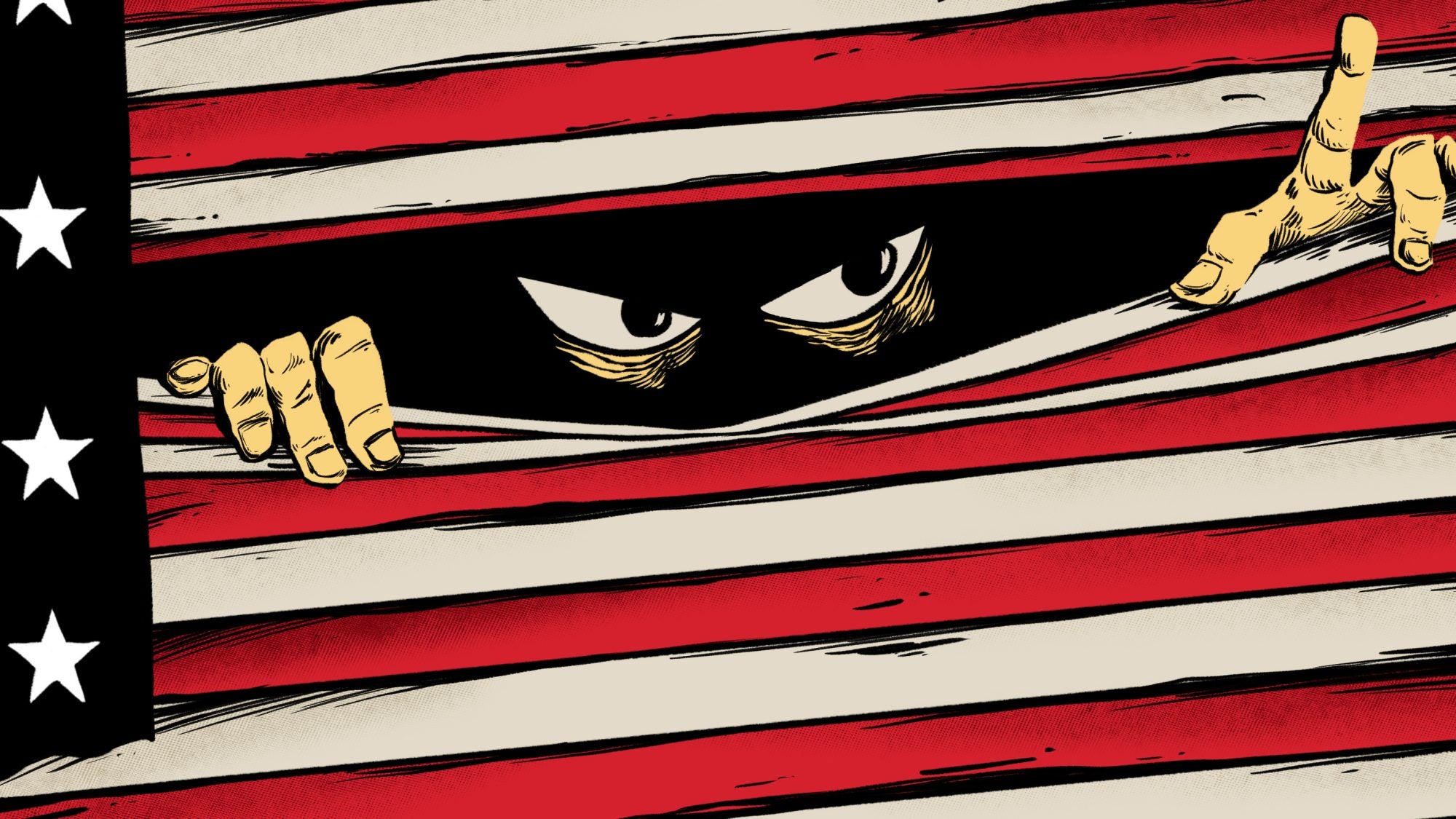

Title: Cyber Mercenaries: Limiting Government Use of Commercial Spyware

Over the past decade, to strengthen its political alliances with countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Mexico, Israel has turned to the NSO Group, a powerful yet controversial company that develops spyware. NSO’s flagship product–Pegasus–allows government clients to remotely access specific individuals’ cell phones, even bypassing end-to-end encryption. After hijacking a cell phone, intruders can capture audio or video, eavesdrop on conversations, track precise geolocation, and reset passwords through two-factor authentication. Because spyware leaves no digital traces of the specific intruder’s identity, it offers high-intelligence returns with minimal risks of detection–making it a sought-after tool for both authoritarian and democratic governments to track targets ranging from suspected criminals and terrorists to journalists, human rights activists, and political opponents.

Recent Trends in Commercial Spyware

The commercial spyware industry, valued at approximately $12 billion in 2023, is highly lucrative and concentrated among a small number of vendors. These companies have experienced more robust global demand since 2014. After whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed in 2013 that the United States National Security Agency’s PRISM program had intercepted upstream communications through popular platforms like Google and AT&T, some countries responded by upgrading their own surveillance infrastructure through tools like spyware. Furthermore, as major US technology companies like Apple and Microsoft began automatically encrypting user communications in recent years, government agencies have sought alternative tools to bypass encryption.

Spyware has become more technically sophisticated in the past decade. During early attacks in 2014, targets would need to click on a malicious link for spyware to hijack their device. To maximize click rates, hackers customized text messages and emails with personal details on their targets’s relationships, careers, and finances. However, these attacks were not guaranteed success, as targets did not always open the malicious link. Several spyware vendors have since upgraded their attack techniques from “one-click” to “zero-click,” exploiting security bugs to embed themselves in software without requiring any action from their targets. For example, the Israel-based QuaDream infiltrated devices by sending calendar invitations containing spyware to their targets, who did not need to accept the invitations to be infiltrated. The targets were often unaware of the attacks because the fake events were scheduled in the past and did not trigger notifications.

Deployment and Risks of Pegasus

Many leading spyware developers like NSO are based in Israel and exclusively cater to government clients. The Israeli government exerts significant influence over companies like NSO through export control laws. Israel’s Defense Exports Control Agency (DECA) has positioned NSO as a central component of the country’s foreign policy strategy. DECA strategically grants or blocks Pegasus licenses to third-party governments to bolster geopolitical alliances. According to The New York Times, Israel licensed Pegasus to both signatories of the Abraham Accords, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain in September 2020.[1] Israel’s Ministry of Defense also pressured NSO to restore Pegasus access to Saudi Arabia in 2019–after the company terminated sales to Saudi Arabia in 2018 due to the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. In addition, DECA has prevented sales of Pegasus to Ukraine since at least 2019, due to Israel’s strategic interest to align with Russia.

NSO states that its goal is to help authorities apprehend criminal entities that might communicate over encrypted messaging services. However, this tool could also be used for less legitimate purposes. Civil organizations and investigative journalists have documented dozens of Pegasus spyware cases that have enabled human rights abuses in countries including Jordan, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic. After Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui published a high-profile story of a real estate deal affiliated with then President Enrique Peña Nieto in 2014, she was bombarded with text messages containing Pegasus spyware links starting in 2016. In 2018, Citizen Lab found that Jamal Khashoggi’s wife, Hanan Elatr, had been targeted using Pegasus technology in the months leading up to his murder, most likely by hackers affiliated with the UAE government.

To prevent human rights abuses, NSO states that it conducts due diligence before selling Pegasus to government clients, assessing risks based on the end-user, duration of the proposed relationship, and the country’s legal protections for free speech. NSO rejected approximately $300 million in new sales between May 2020 and April 2021 or 15 percent of new revenue based on these factors. NSO further requires clients to sign contracts containing human rights and whistleblower protections. Yet, the effectiveness of NSO’s monitoring remains uncertain.

US Policies Addressing Spyware Abuses

Amid rising reports of human rights abuses, the United States has focused on curbing non-US spyware development and use. In 2021, the Department of Commerce (DoC) implemented a rule that limits the export of cybersecurity technologies that could be used to surveil or attack networks and devices to high-risk countries. Most notably, in November 2021, the DoC placed NSO and Candiru on the Entity List. Once on the Entity List, companies can only conduct transactions with US businesses with government approval. This prevents these companies from freely purchasing tools, like iPhones or PCs, to identify potential points of entry. Israeli officials reportedly lobbied against the NSO’s blacklisting, arguing that weakening Israeli spyware firms could create an opening for Russia or China to increase their power over the hacking market. However, these arguments did not change the Biden administration’s position on NSO.

December 2021 represented a turning point in US policy when Apple confirmed the first known spyware case against Americans: eleven employees at the US embassy in Uganda were infected by Pegasus spyware. While NSO has stated that Pegasus cannot target US phone numbers by design, Americans overseas using non-US country codes remain at risk. These discoveries contributed to the Biden administration’s decision to issue an executive order in March 2023 that prevents federal government use of commercial spyware that “poses significant counterintelligence or security risks to the U.S. Government or significant risks of improper use by a foreign government or foreign person.” It announced the executive order at the second Summit for Democracy, in which the United States and ten partner governments pledged to counter abusive uses of commercial spyware–with the notable absence of Israel.[2]

EU Policies Towards Spyware

While the European Union (EU) has imposed substantial fines on US technology platforms like Meta, Google, and Amazon for transferring EU data in violation of privacy laws, its oversight of spyware surveillance among its own member states is more limited. During the 2017 Catalonian independence referendum, at least sixty-three Catalan politicians, political activists, and journalists were infected with Pegasus. NSO acknowledged selling Pegasus to the Spanish government, which is presumed to have orchestrated the hacks; however, Spanish authorities have neither confirmed their targets’s identities nor cooperated with the European Parliament’s subsequent investigation into spyware misuse.

In March 2022, the European Parliament established a committee (“PEGA”) to assess EU spyware usage. It found that at least twenty-two customers in fourteen EU member states had purchased Pegasus, and “authorities in all Member States [most likely] use spyware in one way or another, some legitimate, some illegitimate.” However, PEGA received “minimal or no answers” from national governments regarding their acquisition and deployment of spyware as well as any legal safeguards to protect human rights. Several member states cited national security for this secrecy–which, under Article 4(2) of the Treaty on European Union, “remains the exclusive competence of each EU Member State.” PEGA has warned against using national security as an “excessively broad” justification for commercial spyware surveillance.

In June 2023, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for boundaries on law enforcement’s use of spyware, including a requirement to seek prior court approval for defined purposes and timeframes. The resolution further supported notifying individuals directly targeted by spyware surveillance as well as those indirectly affected through the surveillance of others. It also supported independent oversight of spyware surveillance as well as legal avenues to recourse for impacted civilians. Additionally, the resolution called for a more precise definition of national security as a legal reason for surveillance. In October 2023, the European Commission disclosed plans to issue voluntary guidance on integrating EU privacy and national security standards into their spyware deployment.

A Path Forward

While only a few countries–most notably Israel, the United States, and some EU members–possess the technological capabilities to produce military-grade spyware, these countries can export such technology to over seventy governments, facilitating widespread adoption. In some cases, export controls restricted the development and sales of dual-use technologies, like spyware. However, although the EU passed a new Dual-Use Export Regulation in 2021, PEGA found its enforcement to be “weak and patchy.” Furthermore, the efficacy of export control regimes is weakened if all major export nations do not agree to parallel rules and oversight procedures. Export controls are often circumvented when blacklisted entities acquire prohibited technologies through front companies. In addition, Israel did not endorse the March 2023 Summit for Democracy’s voluntary code of conduct on dual-use technology exports, demonstrating the challenge of multilateralism on the topic.

Many countries have laws to limit traditional wiretapping, but few have enacted formal boundaries on spyware deployment. This is a major gap because spyware (which allows complete retroactive access to data on a device) is more invasive than wiretapping (which permits real-time interception of communications within specified timeframes). Even if government agencies intend to address the threats posed by spyware to public safety, they often lack the procedural guardrails to defend human rights, threatening the legitimacy of any spyware use.

As PEGA highlighted, governments should confine their procurement and use of spyware to pre-defined national security purposes with accountability measures like independent court oversight or audits to prevent secondary misuse. To further promote transparency, governments should annually publish high-level statistics that include the (a) quantity of spyware targets, including their general purposes, nationalities, and other demographic variables, (b) percentage of spyware targets that result in criminal charges, (c) identity of any third parties that receive access to spyware technologies, and (d) description of procedures to protect human rights throughout the surveillance lifecycle. Governments should also notify targets after the surveillance concludes and avenues for those individuals to seek redress if human rights abuses occur.

Moreover, governments should go beyond spyware to limit other types of commercial surveillance that are more common and affordable than spyware but still present high risks to privacy and civil liberties. Such surveillance includes data brokers, social media analysis, and facial recognition. As PEGA acknowledges, “spyware is not to be seen in isolation, but as part of a wide range of products and services offered in an expanding and lucrative global market.”

Even with procedural guardrails for surveillance vendors and governments, unsettled ethical questions around spyware abound. Democratic governments must engage the public to ask if there are situations in which spyware’s invasion of privacy and risks of abuse are necessary. Strong human rights protections should be a minimum baseline, but like-minded governments could consider going further to voluntarily enact moratoriums on the highest-risk procurement and use of spyware. The Summit for Democracy took important steps, but more governments must view spyware not as a tool to advance national security but as a serious risk to them. If left unchecked, escalating surveillance risks eroding privacy, free speech, public trust, and democracy worldwide.

[1] As part of the Abraham Accords, the UAE and Bahrain recognized Israel’s sovereignty for the first time, enabling Israel to normalize diplomatic relations with two powerful regional nations and collaborate on security, economic, and environmental goals.

[2] During the third Summit for Democracy in 2024, six additional governments signed onto the voluntary statement.

. . .

Caitlin Chin-Rothmann is a fellow with the Strategic Technologies Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC. She researches the intersection between technology and society with a focus on US data privacy, antitrust, and content moderation policies.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…