Title: The Energy Transition—Insights from Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State, The Honourable R. Clarke Cooper

In this interview, we speak with R. Clarke Cooper, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs and current nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council. Mr. Cooper explores how Gulf countries are pragmatically adapting to the global energy transition and discusses the importance of broader economic diversification beyond the conventional energy sector.

This conversation is the second in a two-part series. The first part, wherein Mr. Cooper discusses global security and defense strategies amid the intensifying Israel-Gaza conflict, will be published in GJIA’s 26th edition.

GJIA: Now we will move on to the second part of the interview, focusing more on energy and diplomacy. With the global energy transition gaining momentum, how do you see the Gulf countries adapting to this shift? How should the U.S. balance this relationship between its traditional energy partners and the push for renewable energies?

CC: The keyword here is “diversification.” We were just talking about that on the supply chain, right? From a defense side, this is the key buzzword in energy transition everywhere. What I find fascinating about my time in the Middle East is that in the Gulf, there are consistent voices of pragmatism, over the past four to ten years, who say “Yes, we need to diversify.” Then, of course, there is the actual physical manifestation of that diversification in solar farms and wind farms popping up, as well as interest in fusion. Their pragmatism resides in the affirmation that “energy transition will not all happen overnight”—we need to make sure that we are truly having a transition pathway.

There is a sense of urgency that is a little different than that of the West. I am generalizing the West, but we are more focused on emissions—on reducing them—while also wanting to make sure that we are not butting up against a rise of the earth’s temperature and of sea levels. That is a shared global concern, but the difference in transition is that there are transition tools and mechanisms in the U.S. that are economic or government-driven, while in the Middle East, there is a recognition of this transition aligning with a growing global consumer demand.

We spoke earlier about India as a rising state; India is also a rising consumer market for everything. There is a rising middle class demanding not only goods and services but also energy, just like in sub-Saharan Africa. If one wants to get state-specific, Nigeria, has a rapidly growing population of consumers. The world is not shrinking, and hence the point is that there is an increasing need for energy production to meet energy consumption.

In petrostates in the Gulf, they are looking at diversifying energy production, but they are also not looking to immediately shut down petrochemicals and oil. What they are instead looking to do is to bridge it. This is an extremely unscientific metaphor, but I am looking at energy transition as a layer cake. If one thinks of multiple layers in that cake, they are all producing energy, making it not an “either-or” proposition. The day will come when oil ramps off, but for the Gulf, they are looking at it as “we can produce and we will produce oil, but we will build and put in infrastructure for renewables at the same time.”

The other aspect is that if we are going to be pragmatic and we know who is going to be producing oil, then what can we do scientifically on the emissions front? This gets into conversations about carbon capture and how to mitigate or reduce emissions on the burning side, which could be an interesting shift if it gets accomplished in our lifetimes.

Safe to say, however, is that one would be hard-pressed to find anybody in a leadership or corporate government position who is not looking at expanding or diversifying energy. Some are more evangelical about it—I know some people who say they are only going to be focused on green hydrogen as the silver bullet, while others are extremely focused on solar, or fusion. I would take it from a more ecumenical standpoint of the layer cake—a menu of options that needs to be available because it is supremely unfair to tell emerging economies that they need to immediately jump into renewables. They may not be readily capable or nearly have the infrastructure for doing such a transition.

So, who goes first? Well, the more developed states need to add or switch to renewables with more alacrity. And I mean that in the true definition of the sense: put a smile on your face as you do it with speed because developed states are more than capable of doing so. But to assume an emerging market or emerging economy can do it at the same pace is not realistic, hence a pragmatic view on transition.

Maybe it is because of where they sit, but particularly about the energy transition, there is more of a sense of pragmatism in the Gulf state. There, I have heard “it will happen; we are doing it, but it is not an either-or proposition.” It is truly a transition.

GJIA: To build on the idea of economic diversification, how could the U.S. support this overall and broader economic diversification if it means moving beyond energy to tourism or other segments?

CC: Well, it is already happening. And I would not say that the U.S. really must push hard on economic diversification. It is like a swing door to a kitchen—it is easy—in the sense that many sovereign wealth funds or public investment funds that exist have already been diversifying for years. This is not new at all, and why?

The initial driver was pre-climate adaptation, pre-renewables. It was for more practical reasons. If one looks back a little at oil price fluctuations—when I was a little kid in the 70s and 80s, the oil markets were falling over a period of volatility. It scared oil states (or “petrostates”) because if that was a single-source economy or a single driver for their investment funds, which put them at risk. So, diversification for a lot of these funds was driven by oil market fluctuations.

Fast forward to climate interest and climate concerns—those are additional drivers. We talked earlier about the Abraham Accords; that certainly opened some opportunities for investors on getting foreign direct investment into the states. Again, if you are not a co-signer like Saudi Arabia with a public investment fund and looking at what has been beneficial for Morocco, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, you want in on that too. So there has been a natural drive for diversification that existed long before climate adaptation and clean energy became a focus.

What is interesting is that there is also a need or an appetite for strategic climate financing. And so, this is a new space that touches sovereign wealth funds. There is a regional one, the Arab Forum on Environment and Development, or AFED. They focus on reports-based finance and performance-based contracting; they have added impact investing, which is still relatively new. That really touches more—starting with my generation and into yours—where investors want to see something that is not only a return on the money they put in; investors want to see a return on civil society or a return on better communities.

Impact investing is relatively new. Something like AFED is an example of where there has been not only some diversification but also some openness to impact investing and putting back into addressing climate adaptation issues. If one is looking at adaptation, something that I have personally become interested in—from a stability and security standpoint for the region—is addressing water scarcity.

It is a growth space. Indeed, this did not exist earlier in my career—hydro-diplomacy is becoming a practice in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). This is not just about access to water but also producing potable water through desalination and understanding where water can be accessed and shared—not just from riparian rights—but how it can be applied as a tool to mitigate instability.

The reason why water access matters—there are already significant estimates about the cost of climate adaptation in the MENA region. One may have seen recent articles in academic and general periodicals about the rising cost of utilities and air conditioning. Those costs would also include water consumption. So, we are talking about a 14 percent rise in GDP being spent on climate adaptation measures.

If one is working for a sovereign wealth fund or a manager of a public investment fund in the MENA, and they are looking at not only diversifying because they do not want to be dependent on one source of revenue, but are also being practical about what they need to reinvest into their societies and into their neighbours to be able to survive. Some of this is reinvestment in infrastructure. Some of this is reinvestment in being able to have stability because the three macro instability conditions in that region—and globally, but particularly that region—are water scarcity, food insecurity, and mass migration. And one likely does care about that, no matter if one is residing in Abu Dhabi, Doha, or Rabat; those all matter.

So, I offer that when one looks at diversifying the economy or investments, it is partly driven by global conditions greater than geopolitics that require some reinvestment at home.

. . .

R. Clarke Cooper served as U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs from 2019 to 2021, overseeing $170 billion in arms sales and $16 billion in security assistance annually. In 2021, he received the Superior Honor Award for coordinating the security cooperation elements of the Abraham Accords, supporting the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco in normalizing relations with Israel. His over two decades of experience in diplomacy, intelligence, and the military comprise of duty in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and service as U.S. Alternate Representative to the United Nations Security Council.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

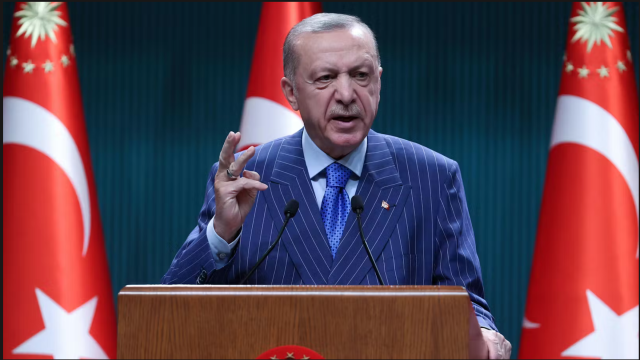

Image credit: U.S. Department of State from United States, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Interview conducted by Spyridon Spyromilios and Harry Yang in October 2024.

More Interviews

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…