Title: Tropical Forests and Climate Change Mitigation: The Decisive Role of Environmental Governance

The Paris Climate Agreement strongly recognized the crucial role of forests for climate change mitigation, as global mitigation goals will require negative carbon emissions. Forest options for climate mitigation include avoided forest loss, improved natural forest management, afforestation (defined by the UNFCCC as “the direct human-induced conversion of land that has not been forested for a period of at least 50 years to forested land”), reforestation (“the direct human-induced conversion of non-forested land to forested… on land that was forested but that has been converted to non-forested”), and improved plantation. However, these options present some challenges. In the case of afforestation, there are biodiversity and water consumption concerns about planting forest species in non-forest systems. Planting exotic tree species could increase CO2 sequestration but at the cost of losing other ecosystem processes and services. While avoided forest loss and improved natural forest management evoke fewer concerns about potential trade-offs, they still imply critical challenges for environmental governance, especially in tropical countries.

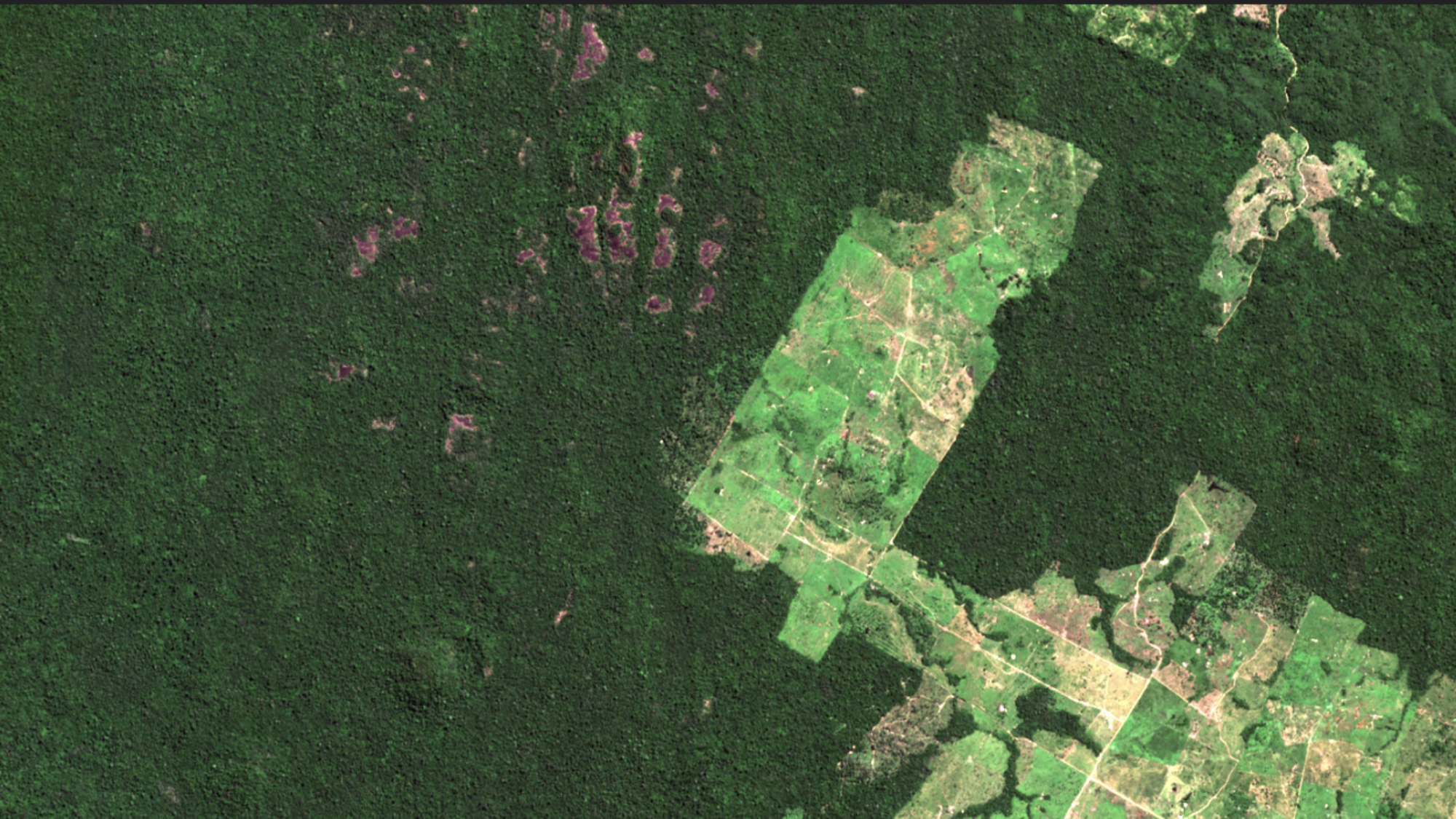

In terms of deforestation control, Brazil’s trajectory in the last two decades is a good example. Five countries around the world (Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Peru, and Colombia) contain almost half of tropical forest carbon stocks, and Brazil has the largest share (around 25 percent). As a mega-diverse country with carbon-rich ecosystems, Brazil’s land-use changes are a global concern. Between 2000 and 2004, deforestation rates in the Legal Amazon increased from 18,226 to 27,772 km2/year. [1] In 2004, the Brazilian government responded with the Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm). The PPCDAm focused on territorial management and land use (for example, expansion of the protected areas network); command and control, through improved monitoring using satellite images and licensing and enforcement of environmental laws; and promotion of sustainable practices, for example, by cutting off public credit for municipalities with higher deforestation rates. Also, in 2008, Brazil created the Amazon Fund, a REDD+ mechanism that raises funds “to prevent, monitor and combat deforestation… [and] to promote… preservation and sustainable use in the Brazilian Amazon.” [2] In 2012, deforestation rates decreased to 4,571 km2/year. The PPCDAm was a benchmark for the articulation of forest conservation policies, and the decline in deforestation after 2008 is mostly attributed to these policy solutions.

Despite the remarkable results, the environmental governance established with the involvement of civil society organizations and forest communities is still very sensitive to federal political dynamics. Environmental protection has always been a contentious issue, mainly because of the economic importance of agricultural commodities in Brazil. However, the country’s political polarization has gradually eroded environmental governance, especially after the changes in the Brazilian Forest Code in 2012, the presidential impeachment in 2016, elections in 2018, and the start of the new federal administration in 2019. Deforestation control policies are being impacted by changes in the new political context with the weakening of the environmental rule of law, forest conservation, and sustainable development programs (for example, changes in the Amazon Fund governance in disagreement with the main donors). In 2019, the annual deforestation rate reached 9,762 km2.

Studies evaluating PPCDAm policies indicate that monitoring and enforcement of the law were fundamental for reducing deforestation. Science was also essential to developing systems for monitoring fires and forest degradation. Stakeholders in the nongovernmental, academic, private, and governmental sectors could track the changes in forest cover thanks to the monitoring systems. Satellite imagery at multiple temporal and spatial resolutions effectively increased transparency by producing alerts for law enforcement, identifying areas undergoing illegal logging and degradation, and indicating the rate and extent of deforestation on an annual basis. Different studies point to the impacts of fires in association with increasing greenhouse gas emissions, economic losses, and deforestation and forest degradation processes.

The creation of protected areas and demarcation of indigenous land was also a critical component, as they constitute an effective barrier against the advance of deforestation. Several studies have confirmed that indigenous lands are the most effective in protecting the forest. Despite this success story, indigenous rights are now also under attack, including constitutional rights related to the demarcation of their territories. The results are an increase in violent conflicts, assassination of indigenous leaders, and invasions of indigenous lands. Satellite monitoring by the National Institute for Space Research detected an increase of 65 percent in deforestation in indigenous territories between 2018 and 2019. Mining is one of the critical drivers of deforestation in the Amazon region and is also associated with pollution and human health problems. Thus, another pressure on protected areas and indigenous lands is the proposal to allow mining in these areas.

The environmental rule of law is essential to climate change mitigation based on forest conservation and management. To quote the United Nations Environment Programme, environmental rule of law “integrates the critical environmental needs with the essential elements of the rule of law” and connects sustainability needs “with fundamental rights and obligations.” For example, the persistence of illegal logging is a massive barrier to using timber markets to promote sustainable use and conservation of forests. Between 2015 and 2016, illegal logging constituted a significant share (44 percent, or about 46,000 hectares) of all tropical timber harvested in Pará state, the largest timber-producing Brazilian Amazon state. Another example concerns the protection of undesignated land in the Brazilian Amazon. This represents 70 million hectares of Brazilian Amazon public forests without formal legal designation, which increases their vulnerability. About 25 percent of illegal deforestation between 2010 and 2015 occurred in this undesignated land, releasing at least 200 million tons of CO2.

Recent estimates reinforce that, in the coming decades, protection, improved management, and restoration of tropical ecosystems are cost-effective and significant options for global climate change mitigation. However, developing countries’ implementation of the forest-based mitigation options in the Paris Agreement would require multiple strategies, including directing mitigation funds to include underrepresented actors and subnational decision-makers, increasing transparency of production and supply chains, developing new mechanisms of dialogue to propose resource-conservation solutions, protecting civil rights, and reducing inequity.

The reduction of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon was possible due to effective political and institutional support for environmental conservation. The array of public policies and social engagement was a historical and legal breakthrough in global protection. However, this structure is now being weakened by the broader political, institutional, and geographic context. Avoiding a critical tipping point of deforestation will require new approaches and arrangements of local and international governance.

[1] Brazil’s Legal Amazon is the country’s “largest socio-geographic division… containing all nine states in the Amazon basin.” The Legal Amazon overlaps three different biomes: Brazil’s Amazon biome, 37 percent of the Cerrado biome, and 40 percent of the Pantanal biome. It was created in 1948 “to promote [the] economic and social development of states sharing the Amazon rainforest.”

[2] As per the UN definition, REDD+ stands for “countries’ efforts to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and foster conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks.”

. . .

Mercedes Bustamante is a professor at the University of Brasília working on ecosystem ecology, particularly related to land-use changes and biogeochemistry in tropical ecosystems, and global environmental changes. She is co-coordinator of the chapter on “Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses” of Working Group III: Mitigation of the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and of the chapter on “Direct and indirect drivers of change in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people” of the 1st Americas Assessment of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).