Title: Indigenous Peoples and Climate Justice in the Arctic

Arctic regions are experiencing transformative climate change impacts. This article examines the justice implications of these changes for Indigenous Peoples, arguing that it is the intersection of climate change with pronounced inequalities, land dispossession, and colonization that creates climate injustice in many instances.

Introduction

The Arctic is warming considerably faster than the rest of the world and will witness the most climate change globally this century. Approximately ten percent of the Arctic’s four million inhabitants who identify as Indigenous experience disproportionate risks to these impacts, as they generally live in remote regions and maintain strong links to the environment through subsistence-oriented hunting, herding, foraging, and fishing. The justice implications of climate change have not been widely examined in the Arctic, however, aside from some studies examining the framing of “dangerous climate change” from a human rights perspective for Inuit communities1,2.

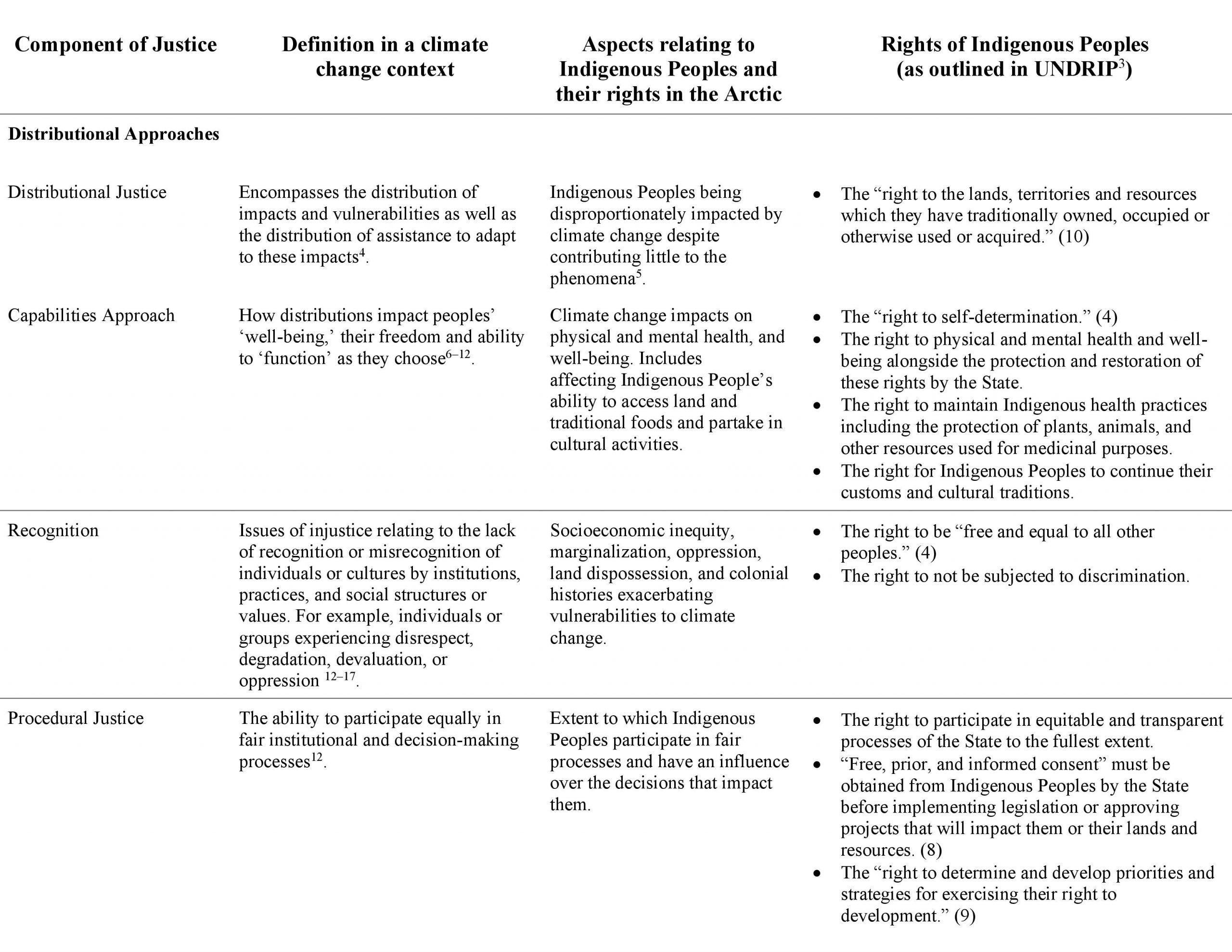

This piece provides a high-level examination of key climate justice considerations as they pertain to Arctic Indigenous Peoples. To do this, we draw upon a rights-based interpretation of justice which encompasses the right “not to suffer” or be adversely impacted by the effects of climate change and thereby achieves climatic justice by ensuring that these rights are protected. Here, we identify and characterize fundamental rights and key issues of distribution, recognition, procedural justice, and capabilities affecting Arctic Indigenous Peoples. Consistent with UNDRIP, we consider Indigenous rights to include: the right to be “free from discrimination,” the right to fully participate in fair decision-making processes, the right to physical and mental health and well-being, the “right to self-determination,” the right to historically owned lands and resources, and the right to maintain cultural traditions (Table 1).

Table 1: Components of climate justice pertaining to the rights of Arctic Indigenous Peoples.

Distributional justice concerns the distribution of climate change impacts and vulnerabilities, and the distributions of adaptation assistance to respond to these impacts. This is particularly relevant in the Arctic where the effects of climate change are already pronounced, as seen in increased warm temperature anomalies, record low sea ice coverage, reduction in sea ice thickness, increase of land ice melting seasons, reduced snow cover, and thawing permafrost18–20. Here, distributional justice encompasses the injustice of socio-economically and/or geographically vulnerable Arctic Indigenous Peoples who experience disproportionate climate change impacts to their health, livelihoods, and well-being21–23.

Many of these impacts threaten or violate the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their traditional or inhabited lands, territories and resources, their right to sustain cultural and spiritual relationships with the land, and their right to preserve and access cultural sites. For instance, coastal erosion and thawing permafrost are destroying or threatening culturally significant archaeological sites across the Arctic. In Alaska, this includes the erosion of an Ipiutak cemetery, while in northwestern Canada, the most significant Inuvialuit archaeological sites are at high risk of deterioration. Climate change is also affecting culturally important wildlife populations and access to subsistence harvests by impeding safe access and travel across the land, water, and ice for hunters and fishers in Alaska, Greenland, Siberia, and Canada24–29. The injustice of these impacts is exacerbated by socio-economic stresses, marginalization, land dispossession and inequity, and rapid resource extraction that many Arctic Indigenous Peoples already face, further increasing vulnerability to climate change.

Unequal distributions are also evident in adaptation policy support. While studies examining adaptation in the Arctic are in their infancy, emerging evidence indicates that—except for the North American Arctic—there is little prioritization of Indigenous Peoples in adaptation policy development or adaptation support to respond to climate change and prepare for future impacts, despite their susceptibility to these impacts and limited contribution to greenhouse gas emissions5,30.

The capabilities approach examines how the distribution of climate-related impacts affect the “well-being,” freedom, and ability of individuals to “function” as they choose, and aligns with their rights to self-determination, physical and mental health and well-being, as well as their ability to practice and maintain customs and cultural traditions. Arctic Indigenous Peoples face some of the highest rates of food insecurity in high-income nations, rates of morbidity and mortality that significantly exceed non-Indigenous Arctic inhabitants, and high levels of water insecurity. These stresses create unique vulnerability pathways and constrain the ability to manage climate change.

Climate change impacts are undermining the rights to health, well-being, and self-determination of Arctic Indigenous Peoples by affecting their ability to “function” and live as they would choose3,12,31. For the Saami in Europe and Russia, some of the most significant health impacts stem from the adverse effects on mental health arising from stress and navigating pressures to change their traditional way of life. Other health impacts of concern for the Saami include: forced changes in diet, increased risks of disease outbreaks and mold exposure, health risks to reindeer and Saami reindeer herders through greater threat of accidents from changes to ice and snow stability, and risks to physical health and cultural well-being through shifts in livelihoods. Health risks related to water quality have also been documented across the Arctic, including increased chemical and microbial contaminants, as well as observations of climatic changes impacting water quantity32,33. Among Inuit communities, ecological grief (felt as a result of “experienced or anticipated ecological losses”) and identity loss have been linked to a diminished ability to engage in traditional activities that contribute to food security and culture, such as travel on the land and subsistence activities, that result from physical changes to the land due to climate change.

The recognition aspect of justice addresses the social structures, institutions, practices, and social and cultural values that prevent the recognition of individuals, communities, and their cultural identities3,12. Many challenges facing Arctic Indigenous Peoples stem from underlying socio-economic inequities which heighten vulnerability and reduce the capacity for adaptation to climate change34,35. These commonly have historical antecedents including marginalization, forced sedentarization, land dispossession, and displacement, which are rooted in colonization36,37. The persistent effects of this historical context have increasingly been acknowledged in the North American context but less so in other regions of the Arctic. However, it has been argued that historic injustices must be considered if we are to address the multifaceted nature of climate change impacts affecting Arctic Indigenous Peoples36,38. Here, justice also encompasses the need to protect and uphold factors that support resilience and adaptive capacity. For instance, maintaining connections to place, agency, and choice with respect to responding to environmental changes, recognizing Indigenous rights and their ability to hold decision-making power in institutions; and acknowledging Indigenous Knowledge in resource and land-management practices.

Procedural justice concerns the extent to which individuals have influence over the decisions that affect them in accordance with their rights to participate completely and effectively in equitable decision-making processes as well as implement their own strategies and priorities3,12. Fair consultation for activities that will affect—or have the potential to affect—Arctic Indigenous Peoples requires not only their participation in decision-making processes but also underpins the need to reach consensus on issues that have competing interests and give “free, prior and informed consent” 3,39. It is common practice for governments across the Arctic to consult with, and provide information to, Indigenous Peoples before undertaking developments or initiatives. However, these practices are insufficient as socio-political institutions and decisions relating to land and resource management often oppose and undermine the agency and self-determination of Indigenous Peoples by failing to include them as partners, acknowledge them as holding positions of leadership, or recognize Indigenous worldviews in decision-making processes36,39. Further complexity can arise from the disadvantageous power dynamics they often face36,39. For example, Inuit in Nunatsiavut, Canada, have expressed the devastating impacts of being excluded from wildlife management decisions surrounding the woodland caribou, which is a culturally significant species that is at risk due to climatic changes and human activities. When faced with decisions that violate their rights, the agency of Indigenous Peoples has been shown to be strengthened through demonstrations of resistance—education initiatives, legal and policy action, as well as other resistance strategies—which often defend their rights to just processes and outcomes.

Conclusion

The rapid and transformative climate changes occurring in the Arctic give rise to complex, interconnected, and rapidly evolving justice issues. Climate injustice is pronounced for many Arctic Indigenous Peoples, created by the interaction of climate impacts with inequities, land dispossession, and sedentarization arising from colonial histories, which create vulnerability and undermine resilience. Additional complexities emerge when considering how climate change might affect future resource development, infrastructure investment, shipping, and migration patterns, the climate justice implications of which need examining in greater depth. Understanding and addressing these “root causes” of climate change injustice is central to research and policy that seeks to promote climate justice and equity—alongside global efforts to reduce emissions—and must underpin broader sustainable development goals in the Arctic.

. . .

Funded by ArcticNet, a Network of Centres of Excellence Canada. The funding did not play a role in the writing of this manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Shaugn Coggins is a Research Assistant for the Climate Change & Global Health Research Group at the University of Alberta. Her research interests include the prioritization of equity, justice, and Indigenous Knowledge in environmental management and climate change adaptation initiatives.

Professor James D. Ford is a Priestley Chair in Climate Adaptation at the Priestley International Centre for Climate, University of Leeds, UK. He works with Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic and globally to understand what makes communities resilient and vulnerable to environmental change.

Professor Lea Berrang-Ford is a Priestley Chair in Climate and Health at the Priestley International Centre for Climate, at the University of Leeds (UK). She works with international organizations and communities to support equitable adaptation to the health impacts of climate change, and to develop methods for tracking global progress on adaptation.

Professor Sherilee Harper is a Canada Research Chair in Climate Change and Health and Associate Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta. Her research investigates associations between weather, environment, and Indigenous health in the context of climate change, and she collaborates with Indigenous partners to prioritise climate-related health actions, planning, interventions, and research.

Dr. Keith Hyams is Reader in Political Theory and Interdisciplinary Ethics at the University of Warwick, U.K. His research takes a philosophical approach to ethics and justice issues in the context of international development and adaptation to climate change.

Professor Jouni Paavola is Professor of Environmental Social Science in the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds, UK. His research examines environmental governance institutions and their economic, environmental and social justice implications, particularly with regard to climate change, biodiversity and ecosystem service provision.

Ingrid Arotoma-Rojas is a Quechua researcher who is currently studying for her PhD at the University of Leeds. She is based in Chanchamayo, her hometown, in the central Amazon rainforest of Peru where she is collaborating with Ashaninka indigenous women to understand and respond to climate change and COVID-19 impacts on their food systems.

Dr. Poshendra Satyal works with the Policy Team of BirdLife International in Cambridge, UK and is an affiliate fellow of the University of East Anglia’s Global Environmental Justice Research Group. His experience and interests are in interdisciplinary and policy relevant research on environment and development issues, particularly on the role and rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in conservation, forest governance and climate adaptation contexts.

Image Credit: Ansgar Walk

References

- Crowley P. Interpreting ‘dangerous’ in the United Nations framework convention on climate change and the human rights of Inuit. Reg Environ Chang. 2011;11:265–74.

- Jodoin S, Snow S, Corobow A. Realizing the Right to Be Cold? Framing Processes and Outcomes Associated with the Inuit Petition on Human Rights and Global Warming. Law Soc Rev [Internet]. 2020;54(1):168–200. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12458

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [Internet]. United Nations; 2008. Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Adger WN, Paavola J, Huq S, Mace MJ, editors. Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2006.

- Climate Change. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Indigenous Peoples. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/climate-change.html.

- Sen A. Well-Being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984. J Philos. 1985;82(4):169–221.

- Sen A. Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Sen A. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books; 1999.

- Nussbaum MC, Sen A. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- Nussbaum MC. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

- Nussbaum MC. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press; 2006.

- Schlosberg D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Fraser N. Rethinking Recognition. New Left Rev. 2000;3(May-June):107–20.

- Young I. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1990.

- Honneth A. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 1995.

- Honneth A. Recognition or Redistribution? Changing Perspectives on the Moral Order of Society. Theory, Cult Soc. 2001;18(2–3):43–55.

- Taylor C. Multiculturalism. Gutmann A, editor. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994.

- Post E, Alley RB, Christensen TR, Macias-Fauria M, Forbes BC, Gooseff MN, et al. The polar regions in a 2°C warmer world. Sci Adv. 2019;5(12).

- Overland J, Dunlea E, Box JE, Corell R, Forsius M, Kattsov V, et al. The urgency of Arctic change. Polar Sci. 2019;21:6–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2018.11.008

- Meredith M, Sommerkorn M, Cassotta S, Derksen C, Ekaykin A, Hollowed A, et al. Polar Regions. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Tignor M, Poloczanska E, et al., editors. 2019. In press.

- AMAP. Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Region [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.amap.no/documents/download/2993/inline

- AMAP. Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Baffin Bay/Davis Strait Region [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.amap.no/documents/download/3015/inline

- IPCC. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [Internet]. Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Tignor M, Poloczanska E, et al., editors. 2019. In press. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2019/12/SROCC_FullReport_FINAL.pdf

- Cold HS, Brinkman TJ, Brown CL, Hollingsworth TN, Brown DRN, Heeringa KM. Assessing vulnerability of subsistence travel to effects of environmental change in Interior Alaska. Ecol Soc. 2020;25(1):20.

- Nuttall M. Water, ice, and climate change in northwest Greenland. WIREs Water. 2020;7(3).

- Laidre KL, Northey AD, Ugarte F. Traditional Knowledge About Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) in East Greenland: Changes in the Catch and Climate Over Two Decades. Front Mar Sci. 2018;5:1–16.

- Ksenofontov S, Backhaus N, Schaepman-Strub G. “To fish or not to fish?”: Fishing communities of Arctic Yakutia in the face of environmental change and political transformations. Polar Rec. 2017;53(3):289–303.

- Cuerrier A, Brunet ND, Gérin-Lajoie J, Downing A, Lévesque E. The Study of Inuit Knowledge of Climate Change in Nunavik, Quebec: A Mixed Methods Approach. Hum Ecol. 2015;43(3):379–94.

- Ford JD, McDowell G, Shirley J, Pitre M, Siewierski R, Gough W, et al. The Dynamic Multiscale Nature of Climate Change Vulnerability: An Inuit Harvesting Example. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2013;103(5):1193–211.

- Canosa I V, Ford JD, McDowell G, Jones J, Pearce T. Progress in climate change adaptation in the Arctic. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15:093009. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9be1

- Watt-Cloutier S, McKibben B. The Right to Be Cold: One Woman’s Fight to Protect the Arctic and Save the Planet from Climate Change. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press; 2015.

- Sohns A, Ford JD, Riva M, Robinson B, Adamowski J. Water Vulnerability in Arctic Households: A Literature-based Analysis. Arctic. 2019;72(3):300–16.

- Harper SL, Wright C, Masina S, Coggins S. Climate change, water, and human health research in the Arctic. Water Secur. 2020;10:100062. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2020.100062

- Ford JD, McDowell G, Pearce T. The adaptation challenge in the Arctic. Nat Clim Chang. 2015;5:1046–53.

- Huntington HP, Carey M, Apok C, Forbes BC, Fox S, Holm LK, et al. Climate change in context: putting people first in the Arctic. Reg Environ Chang. 2019;19:1217–23.

- Ford JD, King N, Galappaththi EK, Pearce T, McDowell G, Harper SL. The Resilience of Indigenous Peoples to Environmental Change. One Earth. 2020;2(6):532–43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.014

- Kelman I, Næss MW. Climate Change and Migration for Scandinavian Saami: A Review of Possible Impacts. Climate. 2019;7(4):47.

- Whyte K. Too late for indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points. WIREs Clim Chang. 2020;11(1):ee603.

- Hughes L. Relationships with Arctic Indigenous Peoples: To what extent has prior informed consent become a norm? Rev Eur Comp Int Environ Law. 2018;27(1):15–27.

Recommended Articles

An estimated 7.9 million Venezuelans migrated abroad for the long term under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule as Venezuela’s political, economic, and social crises have deepened. Alongside rising Venezuelan migration, migrants…

Amid stalled U.S. federal climate engagement and intensifying transatlantic climate risks, subnational diplomacy has emerged as a resilient avenue for cooperation. This article proposes a Transatlantic Subnational Resilience Framework (TSRF)…

The 1997 hijab ban in Türkiye left lasting effects on Muslim women’s psychological, social, and religious identities, shaping their experiences across academia, bureaucracy, and politics. Evidence from interviews…