Title: Northern Ireland: New Trouble for a Post-Brexit Era

The road to Brexit began with an emblazoned bus promising great prosperity if Britain left the European Union. Five years later a bus was ablaze in Belfast. Riots in Belfast, linked to increasing unrest over Brexit, require an urgent response from both the British and Irish governments, but also from the United States. President Biden should intervene to try to find solutions if, as seems increasingly likely, the European Union and the United Kingdom cannot.

On April 7, 2021 a group of young men and children from the Protestant, loyalist Shankill Road area of West Belfast started a riot. They attacked one of the city’s many “peace gates” or walls erected to prevent sectarian violence between Belfast’s two main communities – unionists or loyalists, mainly comprised of Protestants, who wish to maintain Northern Ireland’s place in the United Kingdom, and Irish nationalists or republicans, mostly Catholics, who favour a united Ireland.

Both loyalist rioting and protests in Northern Ireland’s cities and towns in recent weeks were not unexpected. Unionists and loyalists are angry at their political leaders’ failures to prevent what they see as a steady erosion of Britishness since the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement of 1998, which largely ended nearly thirty years of violent conflict in Northern Ireland. Only the United States can command the necessary attention and political will from London, Brussels, and Dublin to find a consensus on a post-Brexit future and restore the Northern Irish peace process to better health.

Adrift in the Irish Sea

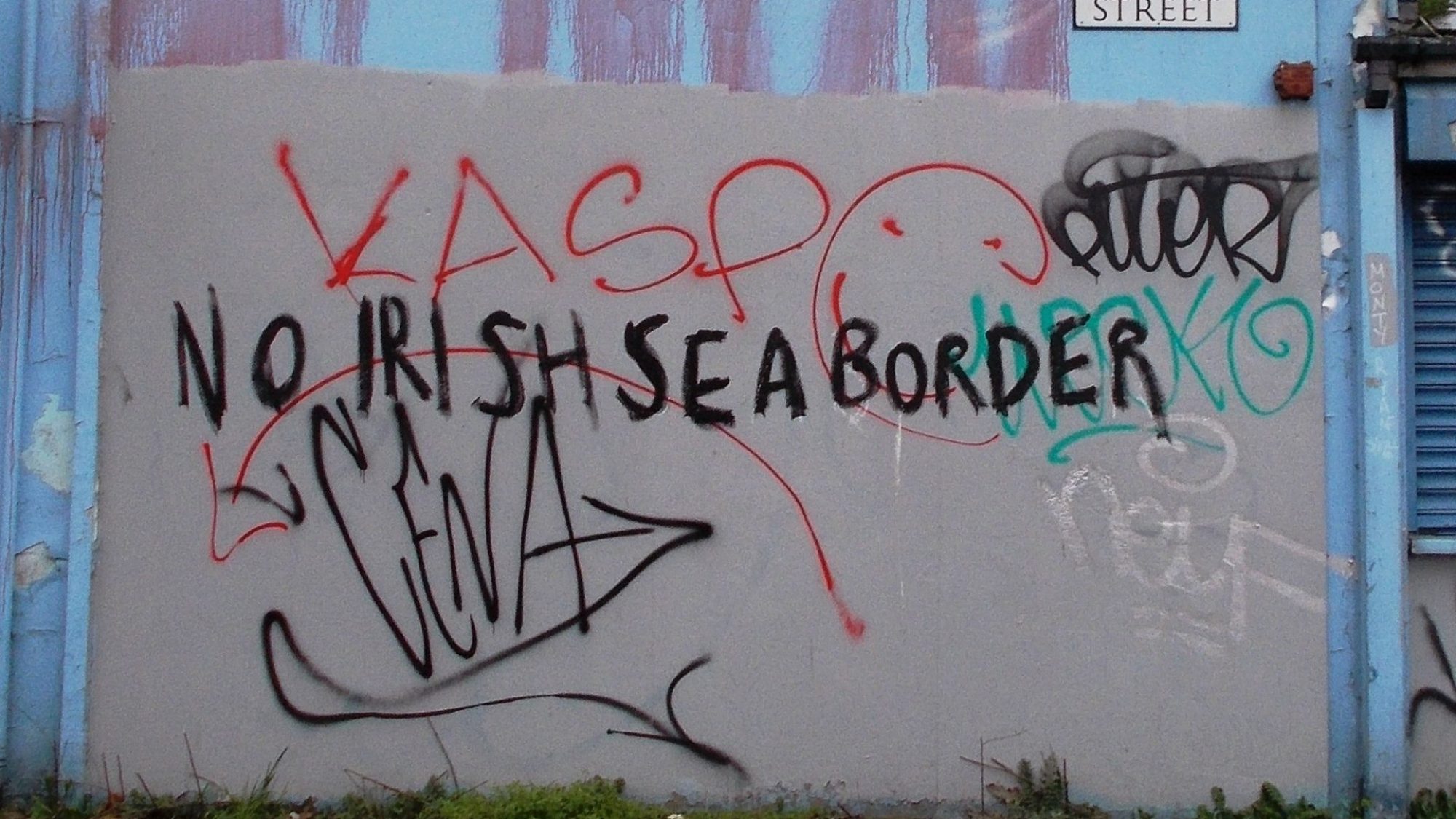

Unionists are particularly outraged by the introduction of what is effectively a new customs and regulatory border in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Northern Ireland as part of a new EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement signed in December 2020. The subsequent failure to prosecute leading republicans in Sinn Féin for seemingly violating COVID-19 restrictions by attending the funeral of Bobby Storey, a well-known former Irish Republican Army leader, served as tinder to the Brexit flame. Leading Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) figures have also demanded the resignation of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) chief constable, Simon Byrne, following the failure to prosecute Sinn Féin leaders for the aforementioned alleged breaches of COVID-19 rules. Byrne refused; the DUP alone cannot remove him. An uncomfortable relationship between the chief constable and the DUP ministers in the Northern Ireland Executive appears to be inevitable.

In recent months Northern Ireland’s largest party, the DUP, sensing the profound resentment within the unionist community and mindful of forthcoming Northern Ireland Assembly elections in 2022, has struck a more populist pose and moved to replace its leader. Former First Minister of Northern Ireland Arlene Foster is closely associated with a series of DUP defeats, not least with respect to the Irish Sea border but also the recent passage of new legislation in London requiring the Northern Ireland Executive to widen access to abortion services. When her successor, Edwin Poots, appeared to give into Sinn Féin-led demands for the immediate introduction of Irish language legislation as a condition of continued shared government, he too was forced to resign after less than a month as leader.

Irish nationalists and republicans believe that the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has only itself to blame for the political and economic damage of Brexit. It campaigned for Brexit, and then refused to back former Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposed Brexit deal with the European Union that would have eliminated the prospect of a ‘hard’ border. When the European Union continued to insist that a customs and regulatory land border on the island of Ireland was a deal breaker for an EU-UK trade agreement, Prime Minister Boris Johnson agreed to put one – under a joint UK-EU Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) – in the Irish Sea instead, something he previously claimed that no British prime minister would ever contemplate.

Polls now show rising support for a united Ireland, even though there is clearly not yet a majority to carry a referendum. The Economist concluded that the DUP had done more to advance a united Ireland than Gerry Adams, the longstanding and erstwhile leader of the republican party, Sinn Féin.

British Obligations and English Nationalism

Such assertions show little understanding of unionists’ sense of precarity when it comes to questions of identity and the logic that underpins the DUP’s awkward embrace of English right-wing parties in Westminster. Since the partition of the island of Ireland one hundred years ago, the question of sovereignty over the north of Ireland has been bitterly, often violently, contested. A complex question like the 2016 referendum – whether British sovereignty should be shared with the European Union – was never going to get a nuanced answer in a place where politics and power-sharing are still very brittle after decades of inter-communal violence.

Sinn Féin’s recent embrace of the European Union in Northern Ireland is in contrast to its past opposition to successive EU treaties in the Republic of Ireland. Unionists remain convinced that such opportunism is proof of Sinn Féin’s strategy to incrementally politically integrate the two jurisdictions on the island of Ireland through a Brussels backdoor of directives and regulation.

Northern Ireland’s unionists have also had to manage the spectre of rising English nationalism masquerading as British patriotism. The fear of England abandoning Northern Ireland has been a perennial one for unionists. Not backing an English Brexit risked provoking a backlash against Northern Ireland among Conservative Party Members of Parliament, many of whom already resent large fiscal transfers across the Irish Sea.

The DUP’s support for leaving the European Union and subsequent alliance with Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party may have been a gamble, and one that failed, but it was not illogical. The subsequent defenestration of the DUP by Johnson and his Conservative government was a shocking act of betrayal that has left Northern Irish unionists reeling.

Instead of expressing incredulity and derision, Irish and EU political leaders (and the esteemed Economist) should show more understanding. Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney’s chiding of Brexit supporters, “You’ve got to own the consequences of your own decisions,” was received badly by unionists. Coveney also later claimed that unilateral attempts by the UK government to modify the NIP were “not the appropriate behaviour of a respectable country.”

Irish frustrations with London are entirely reasonable. Prime Minister Boris Johnson should honor an international treaty he signed a few months previously. But language about the United Kingdom not being a “respectable country” is perceived as a low insult by those unionists who are profoundly worried about the political and economic cost of a border in the Irish Sea. DUP leader Arlene Foster accused Simon Coveney of being “tone deaf” to unionists’ concerns. Relations between Northern Irish unionists and Dublin have reached a nadir not seen in more than two decades.

After days of rioting in Belfast, leading Irish politicians insisted that a British-Irish intergovernmental conference should be urgently convened. The British government rejected such calls, possibly because it looked – following leaks to the media – as if political leaders in Dublin were demanding such a meeting instead of it being jointly proposed and scheduled by diplomats from both countries. Optics and protocol, especially when it comes to both governments discussing unionist and loyalist grievances, must be carefully managed.

Dialing Down Rhetoric and Stepping Up US Diplomacy

In the short-term, Northern Ireland is in for a turbulent summer. Unionists feel that they have suffered a series of humiliations at the hands of the British and Irish governments. It will be difficult for a new DUP leader not to attempt to reverse Edwin Poots’ deal over an Irish language act. The collapse of the Executive seems a real possibility at a time when the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement institutions are needed more than ever. But both governments and the Biden Administration can take steps to try to improve the situation.

First, Dublin should be more attuned to unionist sensitivities over the NIP. Diplomacy in Belfast may reassure more moderate elements within the DUP that the protocol can be turned into a workable, and in some respects, advantageous instrument for Northern Ireland. Micheál Martin, the Irish Taoiseach, has already helpfully suggested that a proposed poll on Irish unity should not be considered in the next few years given the political tensions and uncertainty caused by Brexit.

Second, the British government must stop its denial and obfuscation when it comes to the NIP and instead hold even more intensive and pragmatic talks in Brussels and with Dublin on how to mitigate delays and concerns over checks in the Irish Sea. Claims made by Prime Minister Boris Johnson in an exchange with France’s President Emmanuel Macron that London and Belfast are akin to Paris and Toulouse overlook centuries-old constitutional and administrative divergences in the British Isles and a longstanding British government pledge that it has “no selfish strategic or economic interest” in Northern Ireland remaining part of the union or joining a united Ireland.

Finally, President Biden should appoint a senior Northern Ireland envoy without delay. At the G7 Summit in England in June, President Biden once again demonstrated Washington’s indispensable role in the Northern Ireland Peace Process. His intervention in the days leading up the summit – essentially requesting that the UK government dial down its rhetoric on its objections to the NIP – precipitated a notable shift in tone from London. Only the United States can command the necessary respect, attention and political will from London, Brussels, and Dublin to find a consensus on a post-Brexit future that will avert further violence. Instead of making occasional interventions, the Biden administration must now make Northern Ireland a more fixed diplomatic priority. The health and potential of transatlantic relations are imperiled by this escalating dispute between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Loyalist paramilitaries have a proven record when it comes to casting a veto over political events in Northern Ireland. In May 1974 they helped organise a strike that brought down a power-sharing executive in Belfast. Limited violence in Northern Ireland can bring disproportionate political attention and resources. The DUP will have to decide whether it attempts to secure its vote among moderate unionists or appeals to its more radical, hard-line supporters with the related risk of fostering more instability and recrimination between London and Dublin. The decisions of the leader of a political party in a small corner of Europe may have geopolitical ramifications. In 2021, despite concern over the NIP among many unionists, support for extreme action in Northern Ireland is nowhere near what it was five decades ago. President Biden should help make the logical argument for compromise.

…….

Dr Edward Burke is an Assistant Professor in International Relations at the University of Nottingham.

Image Credit: Whiteabbey under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License

More News

This piece examines the UK government’s proscription of Palestine Action under the Terrorism Act, situating it within a broader trend of shrinking space for public dissent. It argues that the…

This article analyses the distortions of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) notion of proportionality in the context of the Israel-Gaza war. It discusses Israel’s attempts to reinterpret proportionality to justify…

The escalating women’s rights crisis in Afghanistan demonstrates a gap in international legal protections of the rights of women and girls. The international community should fill this gap by making…