In international relations, cities occupy a rich focal point of migration, economic activities, and other distinctive urbanized social formations. The work of Professor AbdouMaliq Simone asks us to reevaluate questions of urban studies through the centering of “Southern Urbanisms,” the everyday ways of living for residents who inhabit cities located in the Global South. In this interview, GJIA sat down with Professor Simone to discuss the significance of Southern Urbanism and how this paradigm can transform our perception of social life in cities.

GJIA: Over the past decades, the focuses of your publications have spanned an immense regional breadth across urban Africa and Southeast Asia. How would you describe your intellectual trajectory within urbanism as a field of inquiry, and what makes you decide to research particular cities such as Jakarta?

AS: The foundations of my involvement began with some work in community action programs I did in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s. During that window of opportunity, there was a lot of focus on building new kinds of urban institutions within poor and working-class communities. Those new urban institutions paved the groundwork for studying how cities were evolving. Subsequently, I worked at various African universities, but because many of them shut down, I had to pursue new ways to make a living. There was much work in West Africa with different Islamic organizations that attempted to figure out new ways of reading and addressing the urbanization processes underway. The 1980s spearheaded a trend of renewed focus on urbanization within the development sector, and I moved into different opportunities abroad with nongovernment organizations, city councils, and a variety of other projects. Many of those opportunities were just fortuitous, and Indonesia was one of these situations: an urban social movement invited me to attend an annual general meeting and then work with them on some projects. I have had the opportunity to work with urban actors in projects across many different geographies, most of which happened by accident.

GJIA: How does prioritizing “Southern Urbanisms” reorient or unsettle the types of questions, understandings, and practices connected to urbanism more broadly?

AS: “Southern Urbanism” is, in one sense, a tagline for altering relationships of power and knowledge: neglected alternatives to Global North-centric spaces, practices, and histories. Southern Urbanism can be seen as a set of moving peripheries from which to challenge authority and knowledge. As urbanist Gautam Bhan said, “the periphery is the geographies of authoritative knowledge.” But at the same time, what would happen if we imagined a periphery everywhere instead of thinking through core-periphery divides that characterize global urbanization processes? There are many global souths—some are extensions of old and new imperial powers, others merge them.

Some southern cities far exceed anything concretized in the so-called North in technical capacity. In these cities, construction booms rest uneasily with deepening impoverishment; the socioeconomic inequalities can be staggering. Cities are torn between becoming mirrors of everywhere or amplifying their local distinctiveness. These cities have spectacularly-built environments, but are coupled with intense predation. Financial investments are everywhere, with high-risk investments in dangerous atmospheres promising the inordinate riches that have long characterized supposedly remote or empty regions. Populations at risk are increasingly seen as such because they fail to take on sufficient volumes of the right kind of risk.

GJIA: Dilip Menon, in “Thinking about the Global South: Affinity and Knowledge,” stresses that the “Global South” does not merely denote a geographic or political agglomeration of decolonized states, but recognizes it as an ongoing project. Thus, the Global South represents a lived reality of its inhabitants, not just a value-neutral theoretical construct at the whim of scholars. Because your work often stresses the creation of unexpected openings and interventions beyond ideas of urban life and how it should function, do you view your scholarship as contributing to the Global South as an active, ongoing project?

AS: I agree with Dilip regarding the Global South being a project. But for me, the Global South is also the unsettling of a project, the undoing of the logic of a project that starts from a particular perspective or aspiration and then materializes itself over time. Instead of seeing the South as embodying specific capacities, enclosures, or potentials, it’s rather important to view it in terms of its various tracks, circulations, and the trajectories it moves beyond clear conceptualization or capture. In some ways, the South is not so much a conceptual designation or a residue of political aspiration or legacy, but something that might be closer to science fiction and made up as it goes along. This is not dissimilar to the chronopolitics (time-orientated) of Afrofuturists, a long-standing series of projects by Black people to write themselves into a future foreclosed to them, to imagine futures devoid of racial tropes.

GJIA: Toussaint Nothias writes that activists from Latin America, Asia, and Africa frequently mobilize to counteract “digital colonialism,” in which mostly US-based technology companies place exploitative and extractive burdens on countries with lower labor and environmental protections. Most recently, news arose that the AI program ChatGPT relied on Kenyan data labeling teams that were paid $2 an hour. In your research, how have you come across this conflict over the use and abuse of technology?

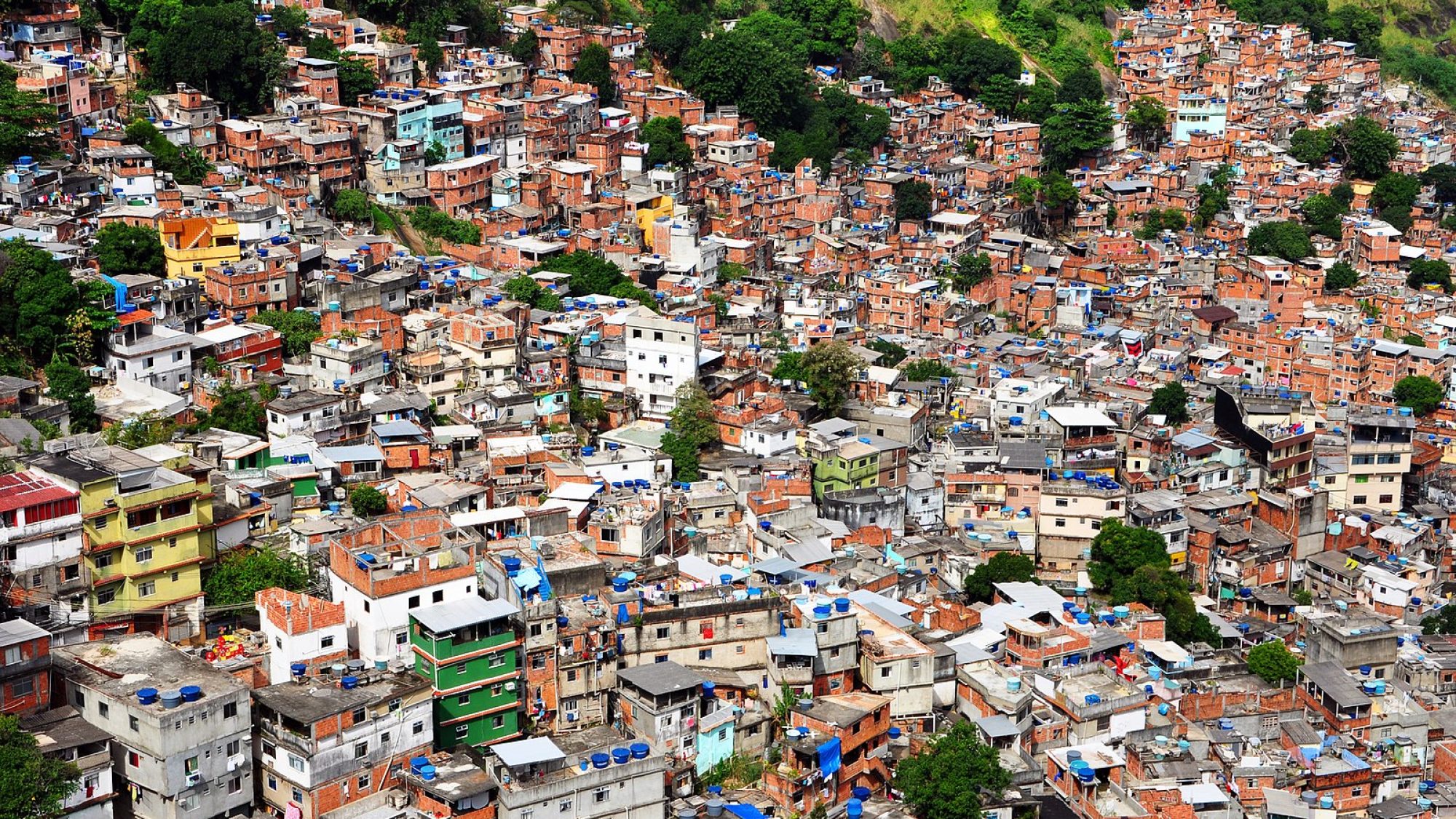

AS: Let me frame this conflict with an example. The MIT Senseable City Lab uses light detection and ranging (LIDAR) 3D laser technology to trace a million data points per second to provide a morphological representation of informal urban settlements. LIDAR thus makes visible spatial organizations that otherwise would remain beyond visualization and thus systematic intervention. The lab created visualizations of one of the largest favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Whether or not the residents of Rocinha can benefit from these visualizations remains a question for the municipal administrations.

While using such mapping technologies might be motivated by the urgency to draw upon, maximize, and enlarge the repertoire of urbanistic sensibilities and resources, a process of valuation is expanded that makes judgments about whose lives count and in what way. Who is sufficiently resourceful or resilient in the favela? Whose bodies can be moved around and tested? And given the increasing volume of terrain deemed uninhabitable due to climate change, security, or toxicity, decisions will be made about what constitutes plausible interventions. Will people in certain circumstances be even more relegated to their devices or become the objects of systematic displacement and relocation?

GJIA: Your most recent book, The Surrounds: Urban Life Within and Beyond Capture, describes “the surrounds” as spaces that residents use in innovative and resistant manners outside their originally designed purposes. Do any particular incidents come up to you that best exemplify this social dynamic, or is it part of the point of “the surrounds” that the generalized categorization of this phenomenon itself becomes problematic?

AS: I like how you framed the choice here, and I will go with the latter. It’s possible throughout all kinds of histories to think about instances of fugitivity, escapism, and withdrawal. Increasingly, one finds these kinds of mechanisms in large urban areas. Still, you can also find it in terms of the inclination of people not to consolidate some position in place, but rather circulate on the move and live through new itineraries where one thing leads to another. This makes the surroundings hard to pin down, and it makes it hard to identify precisely what they are, even through tracking and surveillance of things on the move.

The first point on the notion of surrounds is that you have a kind of process of “exclusionary inclusion,” that is, where the incorporation of marginalized/racialized populations amplifies the arbitrariness of affordances and legal guarantees. This inclusion undermines various autonomous ways in which the marginalized have always attempted to produce and access basic services. It regularizes and makes them part of the normative scheme of things, but that inclusion excludes their own ways of doing things. Another mechanism is “inclusionary exclusion,” that is, the ways in which setting populations outside the norm or social order becomes a zone for working out various contradictions, inefficiencies, and blockages of the order itself. Within the interstice between exclusionary inclusion and inclusionary exclusion is a space that is neither inside nor outside: something that is unintelligible and aside the available binoculars of scrutiny.

The second point is the notion that urbanization is in some ways fundamentally incomplete, that whatever is built is in its very process of making. Whenever you build and whatever you make draws upon materials, elements, and sentiments from all over the place. This situatedness elsewhere pulls at the very coherence of whatever is constructed during urbanization, just as the running of algorithms within smart city programs generates something that is oftentimes incomputable and excessive. And just as in every kind of urban decision support system, no matter how many interoperable variables there may be, you often cannot determine what the eventual decision will mean, no matter how well prepared you are for it.

The third point is that urban accumulation always requires a dispossession of livelihoods, land, and ways of life. Here, the urban becomes a marker of what counts and what does not, of what will be eligible to participate in more significant, more voluminous, or developed processes. If dispossession is a way of taking things apart to put them together in a new way—to make money, to create unique and more specular projects—then what’s loosened up, unmade, or fragmented does not immediately become a component of that more extensive project. They oftentimes have to figure out different ways of intersection. This results in people figuring out new ways to deal with each other that often operate within terms no one understands.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

. . .

Interview conducted by Michael Skora.

AbdouMaliq Simone is Senior Professorial Fellow at the Urban Institute at the University of Sheffield. His research is host to a variety of interlinking spatial subjects, such as the production of everyday urban life in the Global South, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia. His most recent publication, The Surrounds: Urban Life Within and Beyond Capture, was published in 2022 and—through a theoretical combination of Black studies, urban theory, and decolonial and Islamic thought—focuses on how defiant ways of living reshape urban imagination.

Image Credits: Wikimedia | chensiyuan