Title: Interpreting Increased Volatility in Financial Markets

The recent volatility in the stock market has raised questions about its causes and its consequences for asset prices and economic growth. With the 2008 global financial crisis in mind, investors and the broader public want to know whether such corrections are simply part of the process of normalization in the global economy following a prolonged period of unusually low interest rates, or whether they might be symptoms of more worrying trends, signaling a range of other weaknesses in the economy. This article will argue that beyond the challenges created by the global financial crisis and the concomitant rapid rise in levels of public indebtedness in the United States and other advanced economies, policymakers will also face a number of medium-term challenges linked to aging populations and the likely fiscal impact of climate change and that much more needs to be done to establish a firmer foundation for sustainable economic growth.

One area of concern pertains to the current stance of fiscal policy in the United States. Fiscal policy during much of the postwar period has largely been countercyclical, that is, the government has traditionally played a stabilizing role, providing stimulus whenever private demand was weak—such as during the 2008 crisis. Fiscal stimulus was applied globally in response to that crisis, and resulted in a sharp widening of national deficits in the years immediately following. As economies entered a period of gradual recovery, the deficits came down. In recent months, the U.S. government approved large tax cuts and signaled boosts to public spending, at a time when unemployment is at the lowest level in more than a decade (4.1%) and the outlook for economic growth appears positive. These measures raised questions about the appropriateness of fiscal stimulus as a policy tool, considering U.S. public debt levels are at their highest since the end of World War II, reflecting the immense costs of the 2008-09 interventions.

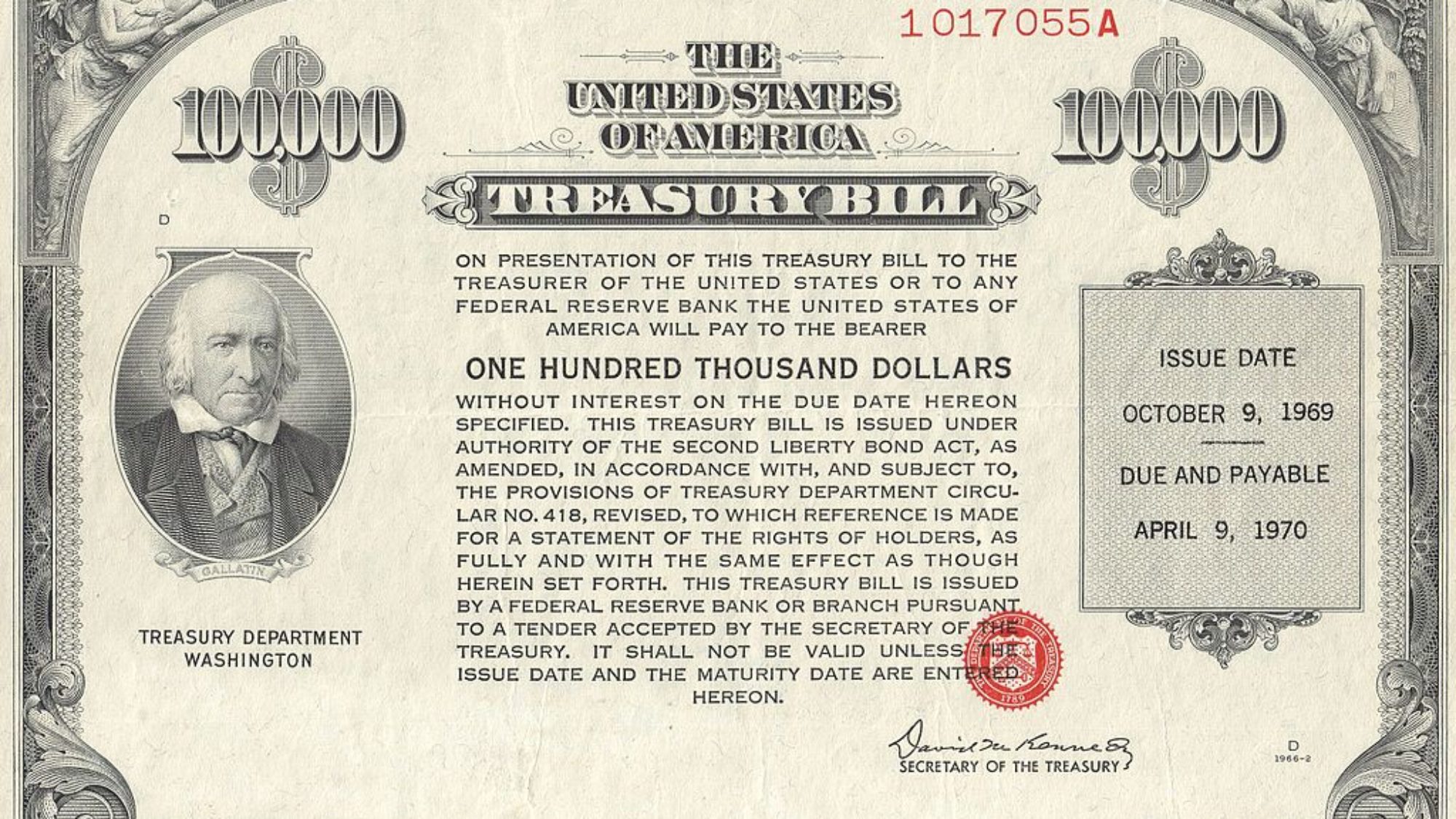

There are other sources of concern in the US. As budget deficits need to be financed, there will be a fairly robust supply of treasury bills to the market in the period ahead. In particular, the US Treasury will have to fund a $1 trillion deficit over the next year. Moreover, monetary authorities already began to unwind their balance sheets, which grew rapidly as a result of the unorthodox policies they were forced to implement – such as quantitative easing – in order to deal with the aftermath of the crisis. Indeed, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England are similarly committed to unwinding their crisis-era stimuli and shifting their role as “babysitters” of the financial markets through the provision of unusually easy financial conditions after the crisis to a more traditional role of guardians of low inflation.

As interest rates in Europe edge up, U.S. debt is likely to be less attractive in relative terms. This effect will be reinforced by the weakness of the U.S. dollar against the euro and other currencies. This is important because the financing of the U.S. budget deficit is very much dependent on foreigners, who own about half of all U.S. debt. In light of this, it has been hardly surprising to see interest rates climb in recent months. This climb has pushed the yield on 10-year treasury bills to a 4-year high. The fiscal outlook is further complicated by these higher borrowing costs. Other geopolitical risks—trade wars, various security shocks—have the potential to boost perceptions of risk and push interest rates higher.

A main concern in the period ahead is not so much about volatility in financial markets linked to a gradual rise in interest rates, or central banks being less accommodating than in recent years. The concern is over fiscal pressures which are projected to build in coming years – for which highly indebted economies are ill-prepared.

As the chart below shows, many countries’ public debts currently stand at levels last seen in the mid-1940s. The problem with high public indebtedness in a context of rising interest rates is that it creates painful tradeoffs for governments. Scarce public resources which could be allocated to areas that help to improve competitiveness have to be increasingly dedicated to debt service. Instead of worrying about reforms aimed at boosting productivity, governments tend to focus more on debt dynamics, market sentiment, credit ratings, and where the money will come from in order to cope with the next crisis.

Regrettably, for a variety of reasons, a number of challenges in the coming years will emerge, which will likely put heavy pressures on the public finances of countries the world over. To start with, unlike the favorable demographic dynamics of the 1950s and ‘60s that featured major increases in the working age population, today, because of increases in life expectancy and decreases in fertility, we face the problem of an aging population. The cost of pensions, healthcare, and other social benefits is projected to rise rapidly over the next several decades. In the United States, for instance, 78 million people were born between 1946 and 1964 (the “baby boomers”), a cohort that has started to retire since 2011. In France and Germany, pension and health spending by 2050 is expected to be well above the 17 percent of GDP registered in 2000. This is not only a problem in rich industrial countries; many of the larger emerging countries have an aging population problem of their own. In coming years, there will be fiscal pressures unseen in past decades, which will significantly add to budgetary burdens and erode the ability of governments to simply “grow out of debt.” Furthermore, governments have generally shied away from implementing the sorts of reforms that are necessary to deal with these fiscal pressures. Increasing the retirement age, for instance, can be a highly effective way to set the public finances on a more sustainable path, though this policy tends to be politically difficult to implement.

Further, climate change will be a feature of the global environment in the years ahead. Increases in sea levels could well require heavy investments in infrastructure, including sea barriers, or, as many regions become drier, irrigation networks and other investments to deal with water scarcity. In some cases, it may be necessary to resettle populations no longer able to live in low lying areas; currently, roughly 1.2 billion people live within 100 km of the shore globally. The increasing incidence of extreme weather events—as we saw dramatically in the United States and the Caribbean in 2017—will also require budgetary allocation that will, by definition, be difficult to plan for. To the extent that weather-related catastrophes put a dent on economic growth, there will be adverse repercussions for government revenue as well, putting additional pressures on budget deficits.

The risk is that markets will not wait until a government is insolvent before significantly increasing the costs of borrowing. 2010 showed how systematically destabilizing the prospect of default could be even for small countries like Greece, and how losses of confidence in the debt-carrying capacity of the country can, through an increase in risk premia, dramatically reduce the government’s room for fiscal maneuver. The point is that the fiscal consequences of climate change and aging populations could at some point interact with financial markets in highly destabilizing ways, significantly worsening an already difficult fiscal situation.

Sustainable economic recovery—essential when addressing the debt problem—will only come when governments implement reforms which will help remove supply-side barriers that have long undermined competitiveness and reduced potential growth. We need to wean ourselves away from central banks’ generosity and courageously tackle the precarious fiscal outlook.

. . .

Augusto Lopez-Claros is Senior Fellow at the School of Foreign Service. He is on leave from the World Bank.