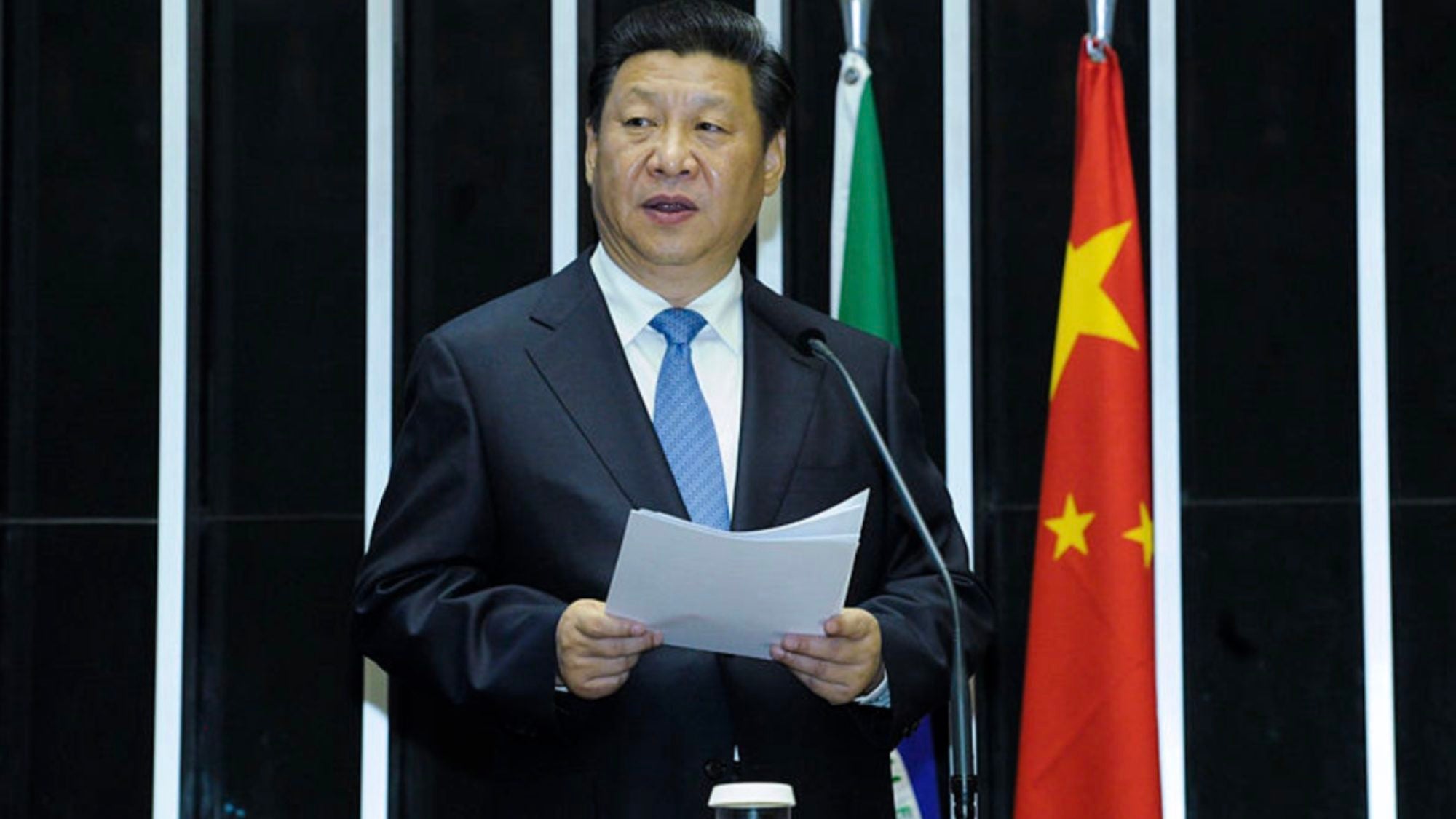

Title: Xi Jinping’s Legacy is not Bridges and Pipelines; it’s his Thought

China is pursuing one of the most significant projects in modern history: establishing itself as a preeminent global power. Four key pillars form this project: “waging great struggles, building great projects, promoting great enterprises, and realizing great dreams.” In order to expand its global reach, China has sponsored The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); constructed artificial islands in the South China Sea and ports from Djibouti to the Pacific Islands, and proposed new global institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Many view these potentially game-changing projects as President Xi Jinping’s flagship initiatives: part of a broader effort to create a “community of common destiny.” However, their scale and ambition have already drawn much scepticism considering China’s economic slowdown and the political instability of partner countries along the BRI. Further obstacles to China’s realization of a rejuvenated society that fulfils its ‘rightful place’ in the world include concerns about debt traps that would bear reputational costs for Beijing and potential clashes with other major powers, particularly Russia and the US.

To many analysts, Beijing’s bold plans come at the expense of soft power. This view is incomplete: Xi’s biggest battle is for hearts and minds in the domestic arena. While international initiatives remain the focal points of the world’s analytic circles and are seen as the key tools of building a new global order, Xi is not content to have his legacy defined by building bridges, pipelines, and artificial islands. Instead, he wants future generations to name him as the one who created a new economic and political order and rewrote the rules of great power relations. These ideological aspirations may pose a significant challenge to the success of China’s more concrete global ambitions. When it comes to ideology, the stakes are raised. If one of Xi’s international endeavours were unsuccessful, it would constitute a policy failure. A failure in the overarching ideology, however, would put the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy at risk.

Ideology Returns

Historically, Chinese political thought hinged upon ideology, from ideas of Marxist class conflict to the Leninist understanding of imperialism, and Mao’s theory of contradiction. Economic failure, however, prompted “reforms and opening up” (gaige kaifang) in 1978. The architect of these reforms, Deng Xiaoping, opened Chinese markets under the banner of “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” and he is largely responsible for modern China’s economic growth. The Soviet Union’s collapse and the obsolescence of socialism produced a post-ideologist China in which the role of ideology was minimized for the sake of a more outcome-oriented approach.

Several decades and multi-trillion dollars of growth later, ideology is again at the political forefront in China. Xi’s recent ascendance to power has been accompanied by the most significant ideological campaign since Mao — constructing what is now branded as “Xi Jinping Thought” — with the “Chinese Dream” as a key component. This “Dream,” which envisions that China’s pre-eminence will generate a future of prosperity, is not only a vision for China, but for the world. Xi’s focus on ideology affects all areas of policy, both domestic and international. While his objectives may be long-term, a recent constitutional amendment cancelling presidential term limits has expanded his horizon indefinitely.

Xi Thought is a rather loose term that encompasses Xi’s moral guidance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and his aspirations to regain the greatness of the Chinese nation under the direction of the CCP. The evolving process of defining Xi Thought is an attempt to reframe the relationship with the country’s past as well as to define a future China. Having transformed into an open-trade market economy, China has long outgrown the Marxist vision of socialism. With Beijing’s geo-economic strategies around the globe also raising imperialist comparisons, Leninist terminology is similarly unwanted.

The Doctrinal Code of the Xi Thought

In foreign policy, Xi Jinping has been much more inclined than his predecessors to articulate visions, norms, and values. Xi’s vision of a new type of great power relations that confronts the predictions of the “Thucydides Trap” and rejects the inevitability of war has led increasingly to a vision of China playing a more central role in the world. In the spirit of creating, Xi puts emphasis on “striving for achievement” (fenfa youwei) – which has now replaced “hide strength and bide the time” (taoguang yanghui) as the central theme of Chinese foreign policy. This effort is nation-wide and comprehensive, transcending domestic and international issues alike. His most frequently articulated vision is “win-win cooperation” or “common development” in all Chinese endeavors. As such, regional diplomacy has been conducted under the banners of “amity, sincerity, mutual benefit, and inclusiveness.”

In domestic politics, Xi’s determination to revive the Communist Party’s glory also involves positive reporting and portrayal in the media. As such, journalists and editors must undergo compulsory ideological training, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for foreign correspondents to have their visas renewed. Social media and internet have involved new and creative methods of control and utilization of online platforms – including engineering new concepts such as “cyberspace sovereignty” and establishing “cybersecurity police stations.” Implementation of Xi Thought is more traditional in schools: introducing courses on theoretical identity with CCP history and ideology, CCP political identity, and CCP emotional identity. Not only does Xi advocate for self-purification, self-improvement, self-innovation, and self-awareness, but his imprint on CCP theories also includes the so-called “Seven Don’t Speaks.” This is a list of forbidden topics that include Western constitutional democracy and the “nihilistic” critiques of the CCP’s traumatic past.

Conclusion

Rarely in Chinese history have ideological quests been peaceful or had a lasting effect. If Xi’s intention is indeed the prevalence of his own ideological legacy, despite his grand global ambitions, the primary challenge will be at home. Xi’s project of reviving the role of ideology is not only a bid for extending CCP legitimacy, but also for transcending the future. Whether Xi Thought can be tailored to the needs (both material and ideal) of future generations remains an open question. Economic performance and national pride remain the primary variables for establishing societal support. This support, in turn, will be necessary to the pursuit of China’s ambitious global endeavors. However, can pride in one’s own nation and faith in the political system be genuine in a society that is discouraged from critical thinking and that has limited opportunities for comparative analysis? The recent elimination of presidential term limits raises numerous concerns regarding Xi’s autocratic tendencies. If Xi indeed concentrates too much effort on building his Thought, he risks treading an abstract path that will do little to win the hearts and minds of his people.

. . .

Dr Huong Le Thu is a senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and associate fellow at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.