Title: Dr. Subham Chaudhuri on Afghan Progress and the Road Ahead

On Tuesday, February 12, Dr. Subham Chaudhuri joined the World Bank Group, along with other experts and World Bank directors, for the launch of the book “Paths Between Peace and Public Service,” and a discussion of the book’s implications for the World Bank’s approach to rebuilding public services in post-conflict countries. Following the event, GJIA sat down with Dr. Chaudhuri to discuss economic growth, education, and prospects for durable change in Afghanistan.

GJIA: What areas of potential growth do you see as most promising in Afghanistan right now?

SC: The challenge for Afghanistan is knowing how to use potential areas of growth. The biggest obstacle to knowing how to utilize growth comes from the problem of conflict. There are two other challenges as well. The first is a lack of capacity, which is needed to exploit those sources of growth; the second challenge is financing, because Afghanistan has tremendous need for development, but there’s a question of how to develop sources of revenue without having money in the first place. One primary source of potential growth comes from agriculture, realizing Afghanistan’s potential for agribusiness. Afghanistan is the home of many high valued items such as saffron, pistachios, fruits, pomegranates, and grapes. Pomegranates from southern Afghanistan can get as much as $7 of $8 a piece in places like Japan. The problem right now has been that forty years of conflict has prevented growth in this particular sector and prevented the creation of jobs in fields such as manufacturing and packaging that are needed in this particular business. Further, a number of food exports were destroyed during years of conflict and all of that has to be rebuilt and financed, which is just a part of the work that we are doing now.

The second potential source is Afghanistan’s mineral and hydrocarbon (oil and gas) resources. You have to develop these resources responsibly, otherwise you’ll end up trapped in a “resource curse.” Whether it is illegal mining or warlords, there are actors trying to negatively exploit the tremendous resources of Afghanistan. These resources should be the primary source of revenue moving forward, but unless the country can find ways to responsibly exploit and use them, the resources will not be useful. The revenues that would result from the mineral and hydrocarbon sectors would also help Afghanistan make its payments. Afghanistan is supposed to export about $8 billion of goods every year; right now, however, it only exports about $4 billion of goods every year, and makes up the difference through grant assistance and foreign aid. If Afghanistan wants to become independent in the future and develop these sectors more, then it is going to need independent revenue from somewhere and that will include royalties from its natural resources.

The third source of growth comes from Afghanistan’s strategic position between Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East, which means the country has the opportunity to be a transit hub. The goods and services transported don’t have to be the only sources of revenue from that strategic location; they could also take advantage of the regional transit of energy, such as electricity. Right now, there is a large project working on transporting energy from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Pakistan through transmission lines in Afghanistan. Not only would Afghanistan receive some of that energy itself, but the fact that it is transporting this energy across its borders to Pakistan is a source of peace in the region. This is similar to the natural gas pipeline that has been built from Tajikistan to India, which passes through both Afghanistan and Pakistan; that, too, has been a source of peace. Afghanistan could be looked at as a source of digital connectivity as well, linking networks between Central and South Asia. Additionally, due to the increasing popularity of hydroelectric power, companies and governments are finding it increasingly useful to have access the warm waters of the Persian Gulf, which they achieve by going through Afghanistan to get to its bordering countries.

The fourth area of potential growth is Afghanistan’s population itself, as the country is home to one of the youngest populations in the world. There are thousands of new Afghanis entering the workforce every year. These young people have a lot of energy, skills, and talents that they can transfer into revitalizing the country’s economy. These are the four main sources of growth, and they have enormous potential, but there are still the challenges of conflict, limited capacity, and financing.

Given the ongoing peace talks between the U.S. and the Taliban, how do you see a potential future deal affecting the political and economic stability of Afghanistan?

The easy answer is that it depends very much on the nature of the peace settlement. A peace settlement doesn’t necessarily translate into widespread or sustainable peace, so I think a lot depends on the nature of the political settlement. It will have to be inclusive in order to incorporate all of the differing views throughout Afghanistan; whatever arrangement is reached will also have to be viewed as legitimate by all parties, making the peace fragile. If the peace is ultimately durable and widespread, that would be a game changer for the future of Afghanistan, as the government, its international partners, and the business community can start investing in people and jobs, exploiting those resources of growth I previously mentioned. Importantly, though, this depends on the nature of the political settlement, as well as the process by which that settlement is reached, as the process will determine how legitimate the agreement is considered. If there is a peace settlement that is widely accepted, then the parties involved will need to start delivering immediate gains in terms of jobs and infrastructure. There will also need to be clear statements from the government and the international community to convey stability and certainty going forward. For private companies and investors, security does matter, but so do the policies put in place by the Afghan government. They don’t want to make investments that they get locked into and then have the rules of the game change on them. There is hope, and I think progress has been made in terms of the momentum of the peace talks, but I do not think that we are there yet with the political settlement.

Strides have been made in the past two decades to improve education in Afghanistan, particularly with regard to women. What do you think needs to be done in future to improve the country’s educational system, both in terms of quality and equality?

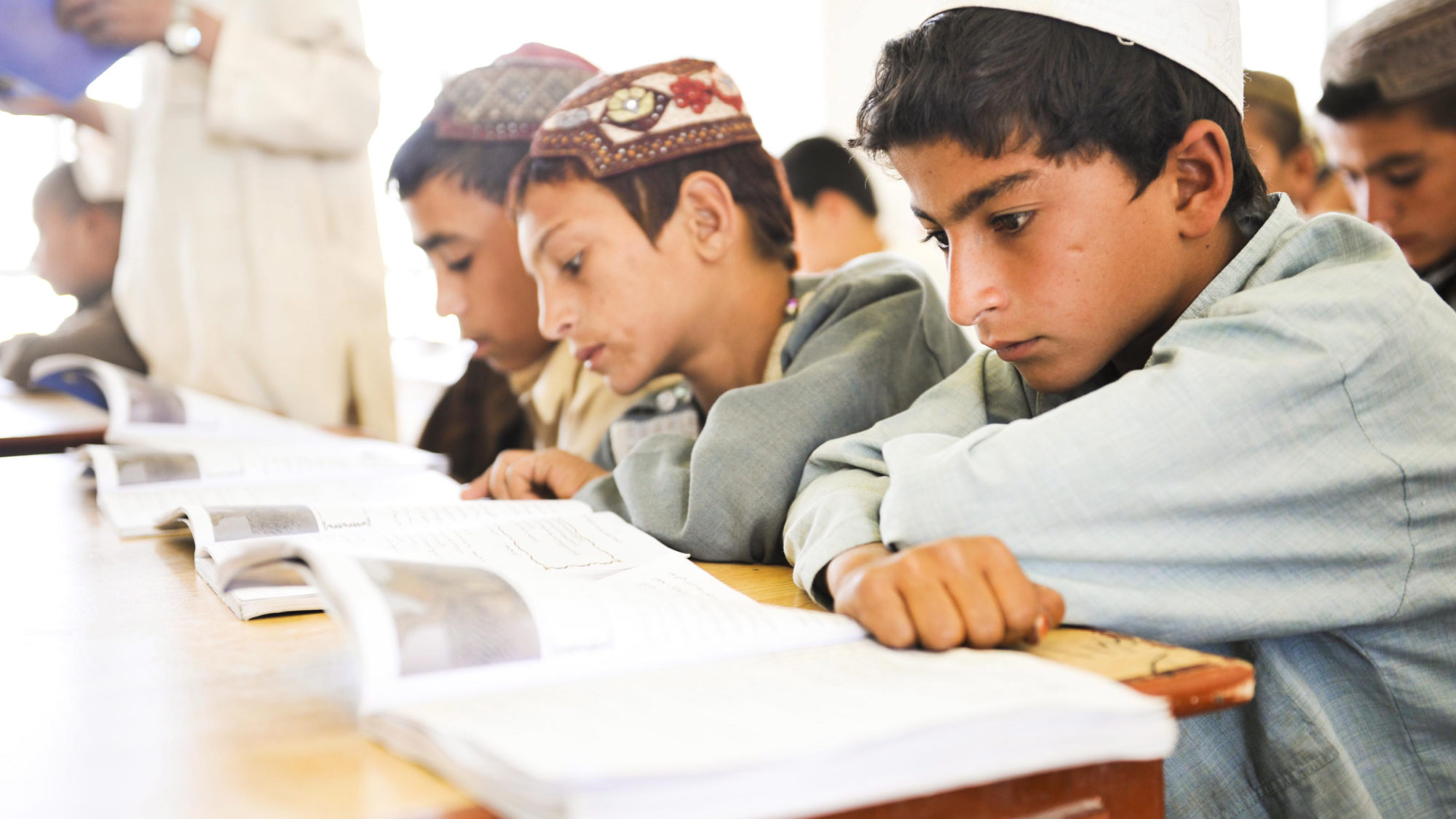

The figures are pretty astounding. You went from a situation in 2000, in which there were fewer than a million children in school and a very small percentage of them were young girls, to today, where you have close to 8.5 million children in school and about a third of them of them are girls. These numbers show that there has been a lot of progress, which is the “glass half full” part. On the other hand, the fact that children are enrolled in school does not mean that they attend regularly; this is true in particular for girls. There does need to improvement in that regard, checking on the attendance rates of these students. Additionally, some children do not have access to proper schools to attend. Let me give you an example. There are 16,000 public schools in Afghanistan under the control of the Ministry of Education. Only about 8,000 of those have physical structures, meaning the rest have the students sitting under tents or under the open sky with the teachers taking attendance and working within a curriculum. Those schools that don’t have physical structures also don’t have walls or bathrooms, which is a serious impediment to having girls attend. Even the schools that do have physical structures might be missing those critical elements like separate toilets for girls. There remains a lot of work that needs to be done in Afghanistan, especially in rural areas and areas that are conflict-ridden, in order to make parents feel comfortable sending their kids to school, especially girls.

It is just as important to note, however, that even in schools which could provide a quality education right now, the numbers aren’t particularly good. Many of the teachers are not very well trained themselves, and getting access to basic materials like textbooks can be difficult; the curriculums probably need some extra attention too. The last global development report said we need to focus on learning outcomes because there are many low incomes countries in which there exist physical structures and schools that kids are attending, but they are not obtaining the quality of education that they deserve and require. Afghanistan is well on its way to solving the challenge of having its students attend school, but now it needs to face challenge of making sure that these kids actually learn, and that the education they get provides them with necessary skills.

The final challenge is that a lot of these gains have been for early childhood education, in what is considered elementary and middle school. There has been, however, an increased rate of attrition once students get to high school, and even more so once they reach vocational training and higher education. The attrition rate is especially high for girls. While the gender gap may be relatively small for the lower grades, as you go up to the higher grades and to higher education, the gender gap in education becomes much more pronounced.

Compared to several decades ago, what positive and negative changes have you seen in Afghanistan, and what do you see for the country’s future in both the short and long term?

The positives in the past few decades are a lot of what I have already discussed. In 2001, Afghanistan was a desperately poor country in terms of education, electricity access, road access, and communication, among other issues. Afghanistan today has made tremendous progress in both education and health care. Given that there is an ongoing conflict, Afghanistan’s child mortality rate is actually better than some low-income countries that are not in the midst of conflict. In terms of democratic governance, women’s rights, and progress on gender equality, there has been tremendous progress. In urban areas, especially in cities like Kabul, the increase of free journalism and the fostering of civil society is something that would not have been seen twenty years ago. On all fronts, there has been tremendous progress from thirty or forty years ago. The unfortunate thing is that the conflict has not lessened, and in some ways, you could say the security situation has even deteriorated, especially in the last five years or so with the withdrawal of some international troops. At the height of President Obama’s surge, there were about 120,000 troops – now that number is down to about 10,000 troops. That has made the security situation difficult for both the Afghan government and civilians, and casualties in both groups have been on the rise.

One other big negative is that Afghanistan has been a recipient of large amounts of foreign financial aid, more than any other country in the world. More than 80% of Afghanistan’s civilian and foreign infrastructure is supported through this foreign aid; on the civilian front, out of about $10 billion of government spending, roughly $8 billion comes from abroad. That has helped Afghanistan make the gains it has, but with such huge amounts of aid poured into the country, there is a worry that some resources may have been diverted in the wrong ways. We talked about the resource curse, in which the natural wealth and resources of a country can corrupt governance, and I see that happening here in Afghanistan. Foreign aid has exacerbated some of the governance challenges which already existed.

Disclaimer: This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

. . .

Dr. Shubham Chaudhuri is currently the Country Director for Afghanistan for the World Bank. Before joining the World Bank, he spent a decade as economics professor and Director of the Program in Economic and Political Development at Columbia University. His research, published in journals such as the American Economic Review, Review of Economic Studies, Econometrica, the Journal of Public Economics, and the Journal of International Economics, spanned a number of areas within development economics including poverty and vulnerability, trade and investment climate, and participatory budgeting and fiscal decentralization. His early work at the World Bank focused on China and East Asia regional policy issues; he eventually became the Lead Economist for Indonesia, relocating to Jakarta in early 2008 to manage the World Bank’s economics team there. Upon his return, he served as the South Asia and Indonesia Practice Manager for the World Bank’s Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice, overseeing the macro-fiscal and economic policy-related work of the World Bank in the South Asia region and in Indonesia. From 2012 until 2014, Dr. Chaudhuri was the manager of the Washington, D.C.-based team of the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Department for East Asia and the Pacific. He received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University and his Ph.D. from Princeton University.