Title: Civilians Versus Their Governments: China, the United States, and the Changing Nature of Conflict and Security in Africa

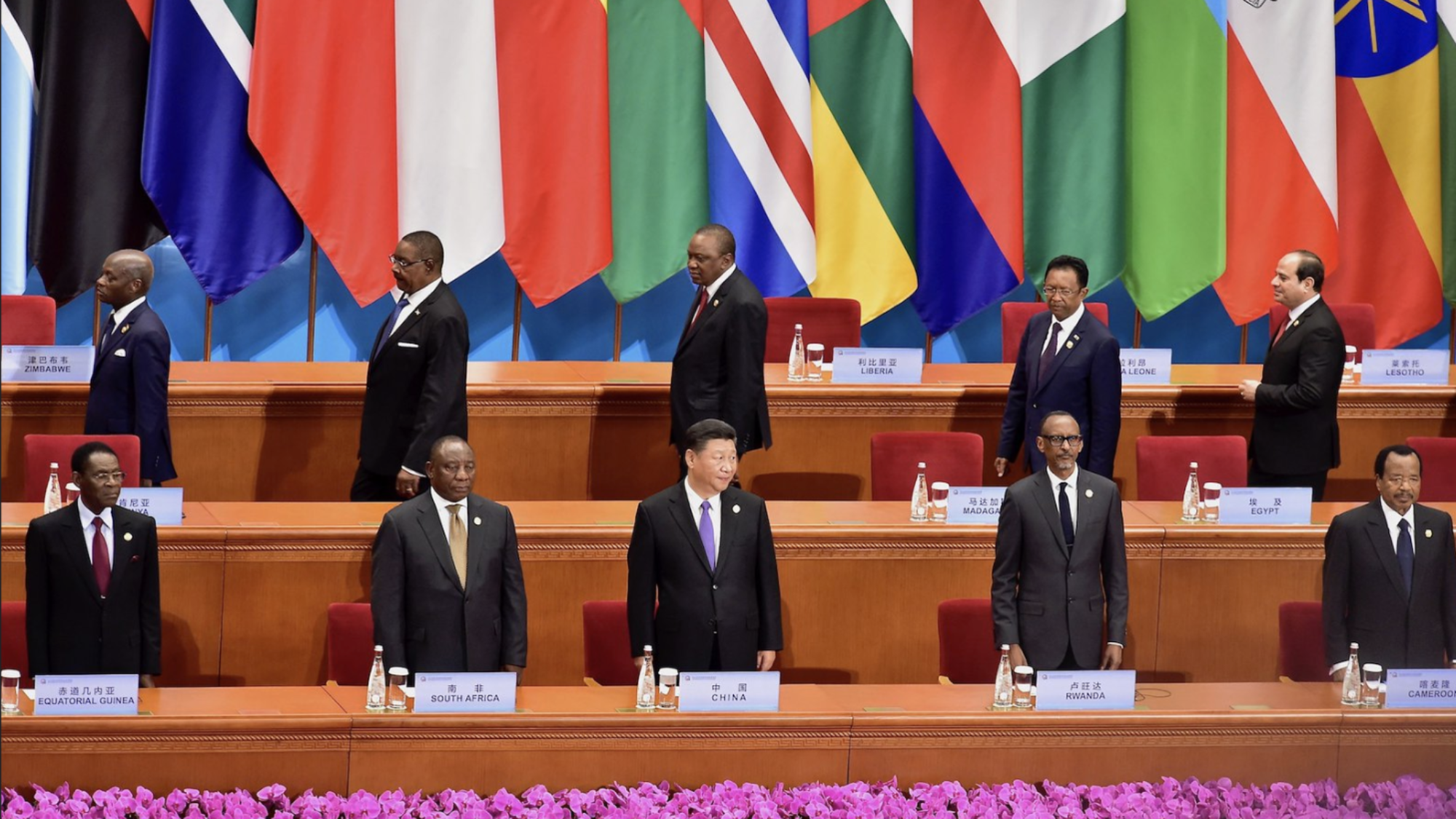

With a few exceptions, armed civil wars are no longer commonplace in Africa, but anti-government protests are. Instead of armed rebels, unarmed civilians are challenging regimes across Africa to reconsider their governance practices and deliver both political and economic change. In their responses, regimes in countries like Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Burundi have favored the combat mode—responding to dissent with military and repressive means. With few options, civilian movements look to the United States for protection and support while their governments look to China for reinforcement. If the United States seeks to reassert its influence in Africa and strengthen its democratic influence, its strategy needs to go beyond counterterrorism and respond to Africa’s pressing needs while supporting the African people in their quest for democracy and human rights.

The United States should realize that the nature of conflicts and threats in Africa has changed. Governments themselves are increasingly the sources of insecurity and violence―usually against perceived opposition supporters. However, the United States’ security strategy is still stuck in a mindset of counterterrorism, and therefore fails to respond to Africa’s prevailing challenges: horizontal inequalities, poverty, weak state institutions, and weak governance. The National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy echo the Trump administration’s “enigmatic approach to the continent.” For instance, the National Security Strategy states: “We will offer [Africa] American goods and services, both because it is profitable for us and because it serves as an alternative to China’s often extractive footprint on the continent.” This was buttressed in the administration’s New Africa Strategy, which focused on advancing “U.S. trade and investment, suppressing terrorism and conflict, and ensuring that U.S. aid is well spent.” Together, the three strategies give an impression that the United States is only interested in Africa to the extent that it advances its geopolitical competition with China. The implication is that, as suggested by some commentators, “Africa will continue to be a low priority for both DoD [Department of Defense] and the administration as a whole.”

The Trump administration’s alleged de-prioritization of Africa in its foreign policy has left a vacuum that China has gladly filled. As the United States pulled out of the UN Human Rights Council, cut support for UN Peacekeeping Missions, and reduced its foreign aid budget, it ensured that “countries that repeatedly vote against the United States in international forums, or take action counter to U.S. interests, would not receive generous American foreign aid.” In contrast, China has shored up regimes in Africa, increasing development assistance and supporting UN peacekeeping and development initiatives on the continent. In September 2015, China announced a 10-year $1 billion peace and development fund to support UN work in Africa. At the same time, the United States cut its budgetary support to the UN. Beijing is also working to link its Belt and Road Initiative with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, advancing its “compelling” narrative that development matters more than liberal democracy. This narrative attacks the core foundations of liberal democracy that the United States has advocated for decades. Yet, there seems to be no urgency in Washington to counter the Beijing narrative, which―due to China’s statist model of economic growth without political liberalization―is gaining traction across Africa.

In July 2019, sixteen of the thirty-seven countries that wrote a joint letter to the President of the UN Human Rights Council supporting China’s human rights record were African, demonstrating how an affinity toward China’s version of human rights is increasing. The letter was a response to an earlier letter written by mostly European countries addressing China’s systematic violation of the Uyghurs’ human rights. This movement in support of China should be concerning to Washington because it demonstrates that China now has allies who will testify for its lack of human rights violations. In addition, the United States’ exit from the UN Human Rights Council resulted in the absence of a strong opposition against China, leaving China with enough room to maneuver other states into its orbit. The most frightening significance of these states’ support is how, as shown by the joint letter, they have internalized the language and posture of the Chinese government without Beijing’s prompting.

China is pushing the narrative that “every country may choose its own path of development and model of human rights protection in the context of its national circumstances and its people’s needs,” and states within the UN Human Rights Council are beginning to accept it. This leads to several implications. First, authoritarian regimes in Africa, such as Zimbabwe, are finding China to be a role model and supporter in their skewed version of human rights, while their citizens, particularly human rights defenders, have no support to fall back on―support that only the United States can provide.

The second implication is that states like Rwanda and Uganda are following the Chinese example of giving pre-eminence to economic and social rights at the expense of civil and political rights. Paul Kagame, widely celebrated in the West for overseeing Rwanda’s extraordinary economic growth, recently warned the opposition that they hide behind politics, democracy, and freedoms while destabilizing the country. President Museveni of Uganda argues that anyone who campaigns against his country is an enemy of development and the state. Both leaders imply that economic and social rights have priority over civil and political rights while collective rights trump individual rights, which authoritarian regimes regard to be disruptive to government-driven development processes. The result is a systematic targeting of active citizenry in Africa, which is the bedrock of democracy.

In addition, the Chinese model is tempting for developing states that experimented with democracy and were hoping for miraculous development but faced disappointment. Not only does it provide economic development, but it also enables the retention of power within a single party. It is not surprising that, over the past few years, several incumbent leaders in Africa have attempted―with varying degrees of success―to remove presidential term limits, which opposes the fundamental ideals of democracy.

The nature of security threats in Africa has shifted. Governments are fighting against popular dissent, with the foundations of democracy and human rights at stake. While the United States’ focus on counterinsurgency and counterterrorism is important, it falls short of addressing the immediate security concerns of the majority of Africa’s citizens. As China increases its political and economic footprint in Africa, regimes deciding between authoritarianism and democracy are being pushed toward the former and increasingly view China as a reliable diplomatic, political, and economic partner.

The United States should consider reasserting its position as a supporter of democracy and human rights, which would entail increasing its support of civil society and non-state actors, not just in key strategic states but wherever authoritarianism manifests itself. Furthermore, the formulation of its strategy in Africa in terms of geopolitical great power competition is patronizing to Africa and, instead of endearing the United States to Africa, further alienates it. Thus, for the United States to be considered Africa’s partner, it must realign its strategies and initiatives with the African Union’s Agenda 2063, which identifies Africa’s key aspirations.

. . .

Obert Hodzi is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom, and co-editor of Democracy in Africa.