Title: Russia’s Energy Paradox: The New Energy Order, Global Crisis, and Enduring Resource Addiction

In 2008, Vladimir Putin told the Russian people: “We will do everything, everything in our power … so that the collapses of the past years should never be repeated.” Despite that promise, in 2014 and now, in 2020, further economic crises have demonstrated Russian leadership’s inability to kick their country’s rent addiction. Russia’s energy woes are clearer in times of global crisis, and their inability to react effectively to periodic struggles is an indicator of an unwillingness to adapt to the fundamental shifts taking place in the industry.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and price war in March 2020, it was evident that the oil and gas industry faced a new energy order. The shale revolution has created a more flexible source of oil and gas, undermining The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and their ability to manage production, while also reconfiguring the global Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) industry. Addressing climate change requires a rapid reduction in fossil fuel consumption driven by falling cost of renewable power generation, as well as policies that aim to tackle urban air pollution, improve energy efficiency, and accelerate decarbonization. In this context, the coronavirus pandemic and resulting unprecedented fall in oil and gas demand preview an inevitable, more definitive shift.

Whatever possessed Russia and Saudi Arabia to engage in a price war amid a pandemic, OPEC+ returned to the virtual negotiating table in early April to agree on deeper cuts in demand, a move triggered by record levels of demand destruction. Russia’s initial hard line was down to Igor Sechin, head of the Russian oil company Rosneft, who believes that the main beneficiary of cooperation with OPEC is the United States shale industry, which has gained market share, but not, as he supposes, at the expense of Russia, which never really reduced its production. The OPEC+ members agreed to a 9.7 million barrels a day cut in production with subsequent discussions within G20 bringing expectations that production falls elsewhere, including the United States, might bring the total closer to 15 million barrels a day. However, demand could fall by as much as 29 million barrels a day in April 2020 and global storage is nearing capacity, with the real price in some producing regions falling to $10 a barrel or less.

The last three recessions in Russia—1998, 2008-2009, and 2014-2015—were all triggered by sharp declines in the price of oil. This is because oil revenues typically account for between one-third and half of Russia’s federal budget receipts; when the oil price dives, so does government spending. But this susceptibility to price changes alone does not capture the true importance of oil in the Russian economy. Revenues generated by oil firms—roughly $1.5 trillion between 1999 and 2013—are also recycled throughout the economy in the form of taxes paid to the government or demand for other goods and services produced in Russia. The Head of the Russia Audit Chamber has said that “the Russian budget may not receive 3 trillion rubles ($39.8 billion) of oil and gas revenues against the oil price of $35 a barrel and the U.S. dollar rate of 72 rubles.”

The recycling of these revenues around the economy ensures that demand for the manufacturing sector remains high. Government spending on social welfare also supports domestic demand, as does state procurement of goods and services, including orders for Russia’s large defense-industrial complex. This dependence of Russia’s wider economy on oil and gas revenues explains why Russia is so susceptible to the fluctuations in the price of oil and why resilience is not just a matter of the size of its foreign exchange reserves.

Having already suffered recessions in 1998 and 2008-2009, Russia’s failure to address its hydrocarbon dependence became apparent yet again in 2014 when oil prices collapsed, causing GDP to decline over the course of 2015-2016. This was exacerbated by its involvement in conflict in eastern Ukraine and Western sanctions imposed in reaction to the annexation of Crimea. In response, Russia’s leaders formulated a plan to boost industrial capabilities outside of the oil and gas sectors, this time through a strategy of import substitution. However, despite the official rhetoric, between 2015 and 2017 investment in oil and gas grew faster than the overall rate of investment, causing its share of investment to rise. Furthermore, the majority of the sectors identified by the strategy are involved in the oil and gas extraction equipment industry. Put simply, the import substitution strategy perpetuated the dependence of the wider economy on the hydrocarbon sector, contrary to stated strategic goals.

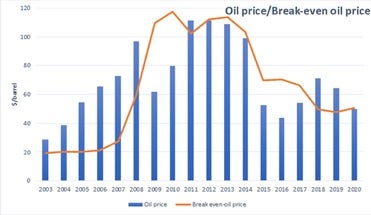

Figure 1: Oil Price versus Break-break even oil-price (Source: Bloomberg/Nordea Bank)

Russia’s recovery from the 2014-2015 recession was slow. Between 2014 and 2019, the average rate of annual economic growth was lower than 1 percent. Government spending has been reduced to avoid the need to slash spending should the price of oil fall (see Figure 1). In 2013, a price of over $100 p/b was needed for the budget to break even; in 2020, $42 p/b achieves a balanced budget (significantly lower than Saudi Arabia, which needs $82 p/b). Oil and gas tax revenue on a price above $42 has gone into the National Wealth Fund (NWF). Consequently, the finances of the government improved substantially, but living standards have declined. In early 2020, gross government debt is 15 percent of GDP and foreign exchange reserves stand at $570 billion, including over $150 billion in the NWF. Furthermore, a flexible exchange rate ensures that if the price of oil drags the ruble down with it, Russia’s cost competitiveness improves as domestic production costs decline. However, the cost of imports increases, imposing an additional burden on domestic consumers and driving inflation. The Kremlin is aware of the hardships imposed on Russian society. In January, President Putin announced plans to spend over 25 trillion rubles (around $415 billion at the January exchange rate) on ambitious ‘National Projects’ to boost infrastructure and social welfare. But these plans may be derailed by the slump in oil prices and the looming global recession.

Russia’s Ministry of Energy submitted the latest version of Russia’s Energy Strategy to 2035 in late 2019, five years late, and it was finally approved on 2nd April 2020. An evaluation of the draft Strategy has described it as “struggling to remain relevant” in the face of the global energy transition. The principle policy goal remains increased energy exports and revenues; however, the scenarios presented suggest that, after 2025, Russia will struggle to maintain oil production and develop new reserves, in part due to sanctions. By comparison, gas exports are expected to grow through new markets in Asia and expanded LNG production.

The Russian government’s latest climate targets for 2030 “lack ambition,” and its climate action plan sees socio-economic benefits for the country, such as the opening up of the Northern Sea Route to develop the Arctic’s hydrocarbon potential. At the same time, Russia’s new energy doctrine identifies international climate efforts and the shift to a green economy as a foreign policy challenge that might limit its ability to export oil and gas. Overall, these strategies deny the tectonic changes afoot in global energy markets and do nothing to reduce Russia’s hydrocarbon rent addiction.

Russia faces an energy paradox: investment in green growth requires financial resources that can only really be earned by the export of hydrocarbons. Once again, these export revenues are threatened. Facing a fourth oil price-induced recession in a little more than twenty years, now is the time to ensure that Russia’s economic development is fully aligned with the logical consequences of the coming energy transition. Should they fail to do so by the end of this decade, the opportunity will be missed.

. . .

Michael Bradshaw is Professor of Global Energy at Warwick University Business School and Co-Director of the UK Energy Centre (UKERC).

Richard Connolly is Director of the Centre for Russian, European and Eurasian Studies (CREES), University of Birmingham.