GJIA: What does the future of antitrust look like? Is it likely any of the measures called for in the House Report would ever be implemented?

One of the big things we talked about are movements to attack appropriation and self- preferencing. But another big movement and makes up a substantial part of the Report is that Congress wants to overrule ten-odd Supreme Court precedents in antitrust. These precedents have made it exceedingly difficult for plaintiffs to prevail in an antitrust case. In fact, it is so hard, that something on the order of ninety-eight percent of plaintiffs fail in these Section Two monopolization cases. It is a really, really low win rate. It is so low that you could imagine that a lot of plaintiffs and government regulatory agencies would say “why would we ever invest millions of dollars or more in an antitrust case, if our win rate is going to be two percent?” If Congress takes the House Subcommittee up on this task and overturns these ten pro-monopoly decisions that the Supreme Court has made over the last twenty years or so, I would expect that antitrust would be reinvigorated. You would see a bunch of cases that would not otherwise have been brought [to the courts] because the playing field was so hostile to players.

GJIA: Do you have any other recommendations for antitrust regulators or any lasting thoughts that you want to share?

I do think that the House Report is a nice template and a nice place to begin. They certainly picked upon my favorite idea, which concerns non-discrimination. One other area that I would push antitrust enforcers is to take an aggressive approach to worker welfare. We are starting to see this a bit; there are new cases that are being brought by private enforcers, at least with respect to no-poach agreements among the fast-food franchises. So, no-poach and non-competes are important areas.

But I fear that we are going to have a world where a defendant will be able to point to clear harms to workers that come about from some restraint that might be offset, in theory, by a benefit that the defendant splashes in the direction of consumers or end-users. This came up in a famous NCAA case where the defendants essentially said that they need to conspire to not pay students to play sports because surveys suggest that viewers attach a certain value to knowing that the students are out here not for the payment but for the love of the game. This was actually able to sway the court to allow the conspiracy to not pay the students. We need to do some cleaning up and maybe the proposed reversal of the Supreme Court’s Ohio v. American Express will get at it. We need to get to a point where if a plaintiff can show harm, whether it is to a worker or a merchant, and connect it causally to some kind of restraint, the inquiry should end. The idea that a defendant can point to some other third party and say that they benefit from the restraint and that their gains should be somehow used to offset the known harms, that to me, is going to be the next hot area of antitrust. I would hope it goes in one direction, which is no offsets, but I think your readers should stay tuned to see how that develops.

. . .

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

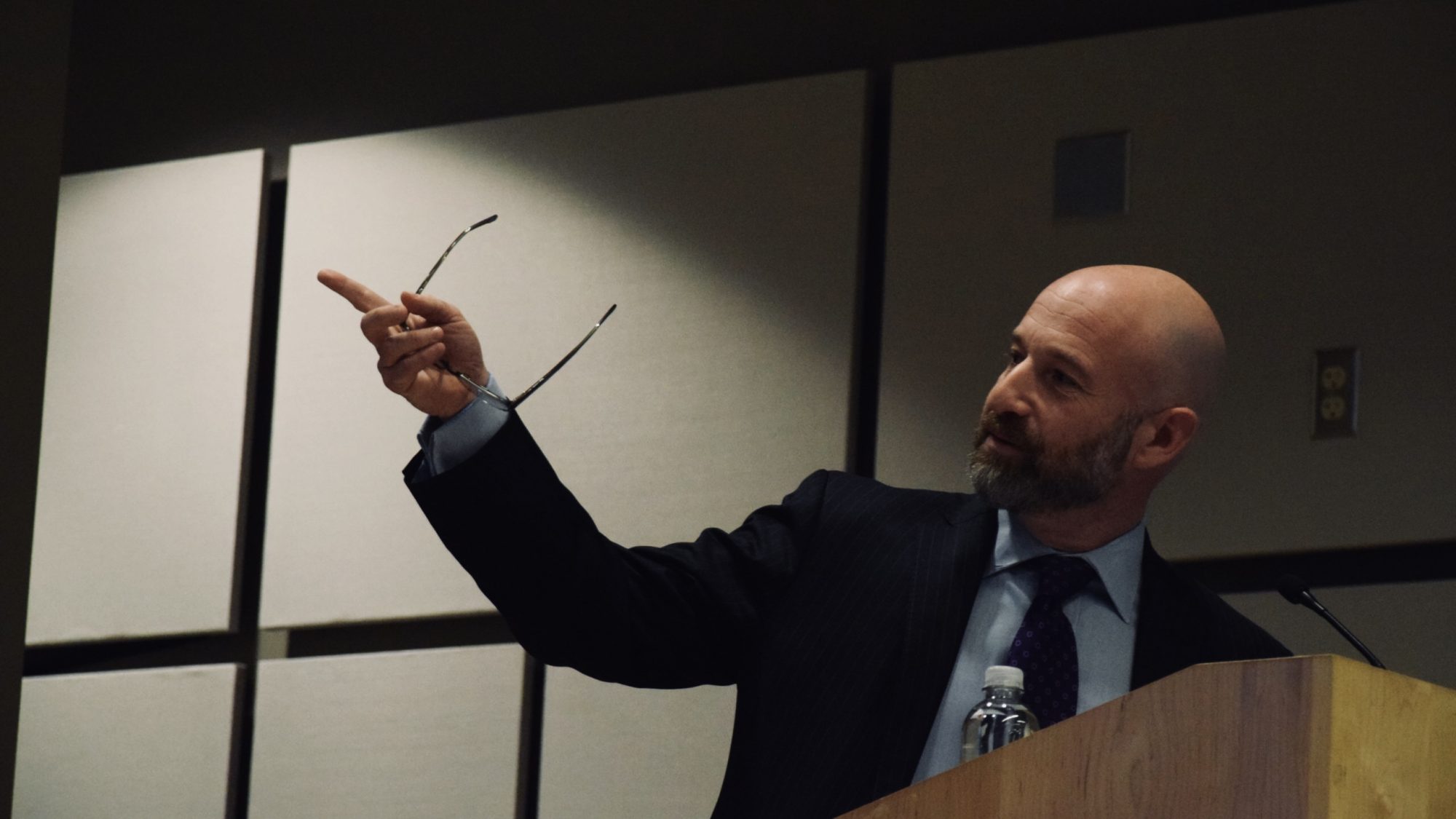

Dr. Hal J. Singer is a managing director at Econ One Research, a senior fellow at the George Washington Institute of Public Policy, and an adjunct professor at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business. He is a co-author of the e-book The Need for Speed: A New Framework for Telecommunications Policy for the 21st Century (Brookings Press 2013) and co-author of the book Broadband in Europe: How Brussels Can Wire the Information Society (Kluwer/Springer Press 2005). Dr. Singer has testified before Congress and has been widely cited by courts and regulatory agencies, including the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Department of Justice. His Twitter handle is @HalSinger.